Two clown fish and many threespot damselfish swim around a giant carpet anemone on a coral reef in the Asan marine unit of War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam/NPS

America’s Reeling Reefs

By Jonathan Horwitz

The first standardized national assessment of coral reefs in all U.S. states and territories finds that conditions in vital marine ecosystems are fair but vulnerable and declining. “We’re buying time,” one NOAA marine biologist says of reef conservation efforts in the face of climate change.

When considering the array of naturescapes within America’s national parks, picturesque scenes of giant trees and jagged mountains come to mind à la Albert Bierstadt paintings and Ansel Adams photographs. Yet, some of the National Park System’s most vibrant environments aren't in clear view to be seen with the naked eye or captured by most cameras.

Hidden offshore and underwater, coral reefs host the greatest biodiversity of any marine ecosystem on Earth, supporting one-quarter of all marine life worldwide. In the United States, the National Park Service along with other agencies within the Department of the Interior have jurisdiction over 3.6 million acres of reef habitats across 88 ocean and coastal parks, including 10 national parks.

That acreage grew in 2016, when then-President Obama designated the nearly 5,000 square-mile Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Monument some 130 miles off Cape Cod. The monument "includes two distinct areas, one that covers three canyons and one that covers four seamounts. These undersea canyons and seamounts contain fragile and largely pristine deep marine ecosystems and rich biodiversity, including important deep sea corals, endangered whales and sea turtles, other marine mammals and numerous fish species."

When Obama designated the monument, then-Interior Secretary Sally Jewell said the designation would "help protect the unique geology and biodiversity of these important underwater features and wildlife species that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. This critical marine area, which serves as important habitat for pelagic fish species, corals, whales, sea turtles, sea birds and other species, will now be protected and preserved for future generations, serving as an important natural laboratory for research and enhanced understanding of the impacts of climate change on our oceans.”

(While President Trump relaxed some of the protections the monument was given, the Biden adminstration is expected to be asked to restore them.)

“Growing up in the Midwest, when I thought of national parks, I thought of bison and bears, not coral reefs and elephant seals,” said Eva DiDonato, chief of ocean and coastal resources programs at the NPS. “Perhaps the word ‘park’ implies land to a lot of people, but the NPS is hard at work protecting ocean and coastal resources, too.”

Understanding the process of coral bleaching/NOAA

National Park System reefs span the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and range from extremely remote to remarkably accessible. The National Park of American Samoa, home to 250 tropical coral species, is the only national park south of the equator. Meanwhile, in Florida, Biscayne National Park, which encompasses 5,000 coral reef patches, is less than 20 miles from Miami Beach, the eighth-largest metropolitan area in the United States.

Near and far, coral reefs rank among the most sensitive ecosystems to increased human activity, climate change, and a litany of other local and global stressors. “The most pressing challenges and threats facing NPS reefs today include loss of coral due to bleaching, disease, ocean warming, ocean acidification, land-based pollution, overuse of reef resources and invasive species,” DiDonato said.

Plastics pollution also is a key threat. According to Ocean Conservancy, “(E)very year, 8 million metric tons of plastics enter our ocean on top of the estimated 150 million metric tons that currently circulate our marine environments.” A 2018 study published in Science pointed out that “(B)illions of plastic items were entangled in the reefs. The more spikey the coral species, the more likely they were to snag plastic. Disease likelihood increased 20-fold once a coral was draped in plastic. Plastic debris stresses coral through light deprivation, toxin release, and anoxia, giving pathogens a foothold for invasion.”

In spite of public and private sector strategies to mitigate these threats, reefs are vulnerable and declining, according to the first standardized national assessment of coral reefs in all U.S. states and territories by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Through our conservation and restoration efforts, we’re buying time to ensure that we don’t lose the genetic integrity of coral species,” said Dr. Andy Bruckner, research coordinator at NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuaries Program.

Declines in coral coverage at Biscayne National Park/NPS

Currently, NOAA lists 22 coral species as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Species seen by many snorkelers in national parks, elkhorn and staghorn corals, are both considered to be critically endangered.

“Until we really get a handle on climate change, reefs are going to continue to face significant challenges and threats,” Bruckner said.

For these reasons, unfortunately, America’s marine parks find themselves on Traveler's list of threatened and endangered parks.

Reef conservation is important for the environment and the economy.

“Not only are reefs nursery grounds for a host of marine organisms, but they also provide ecosystem goods and services to coastline communities,” said Caroline McLaughlin, Sun Coast regional associate director of the National Parks Conservation Association.

The Great Florida Reef has an asset value of $8.5 billion, generating $4.4 billion in local sales, $2 billion in local income, and 70,400 jobs in southeast Florida, according to NOAA. In addition, U.S. reefs provide $1.8 billion in flood protection services and spawn $200 million in commercial and recreational fisheries. However, a debate over how to sustainably manage commercial fisheries in the parks has embroiled the NPS in a lawsuit with NPCA over the health of Biscayne’s reef.

Flourishing interest in coral reefs is a double-edged sword. In the past half-century, live coral cover has declined by as much as 90 percent in critical reefs within and around national parks. Initially, local issues associated with urban development, overfishing and tourism over-use constituted the principal stressors to their health. By the turn of the century, over 11 million tourists vacationed in Hawaii and four million more visited the Florida Keys annually, contributing more than $1.5 billion in tourism-related services to those states’ economies.

Damage to corals at Virgin Islands National Park either from 2017 hurricanes or large February 2018 swells/NPS

Despite their economic and recreational value, human activity was pushing these fragile habitats to the brink of survival. Recognizing the need for intervention, Congress took a series of actions to shepherd healthy reefs into the new century, including the passage of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Protection Act in 1990 and the establishment of Dry Tortugas National Park two years later. In response to the first global coral bleaching event in 1998, President Clinton signed Executive Order 13089, creating the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force, a collaborative effort between nearly two dozen state and federal agencies committed to the preservation, restoration and sustainable use of reef ecosystems, of which the DOI is co-chair.

Although the Task Force assembled a national plan to conserve reefs in 2000, global trends such as elevated ultraviolet radiation and ocean warming have accelerated their degradation in the last two decades, according to NOAA’s Bruckner. Atypically warm and long El Niño cycles in 2010 and 2014-2016 led to consecutive bleaching events from which reefs in Hawaii, Florida and the Caribbean have not fully recovered.

After most El Niño events, reefs ordinarily rehabilitate as water temperatures cool to normal. Yet, climate change means that average ocean temperatures are perpetually on the rise. On top of that, Hurricanes Irma and Maria decimated Atlantic and Caribbean reefs in 2017. In the aftermath of these extreme weather disturbances, live coral cover plummeted by 60 percent in reefs within Biscayne National Park and by 20 percent in Virgin Islands National Park. The following year, Cyclone Wilma wiped out entire reefs in the South Pacific.

Biscayne’s staff tried to gain a measure of protection by calling for a 10,522-acre marine reserve around its coral reef, but politics blocked that move. NPCA attorneys, pointing out that the Park Service has a mandate to “conserve the scenery; natural and historic objects; and the wildlife therein,” sued the agency in December in a bid to see the reserve created.

“Corals, which, in fact, are immobile animals - not plants - are translucent,” explained Dr. Jennifer Koss, director of the Coral Reef Conservation Program at NOAA. “It’s microscopic algae in their tissue that give them their vibrant blue, purple and pink colors and provide the majority of their nutrients.”

Boulder brain coral (Colpophyllia natans) surrounded by star coral (Orbicella spp.) show gradations of color termed "coral bleaching" - the loss of symbiotic algae in response to elevated water temperatures at Mennebeck Reef, Virgin Islands National Park/NPS

In unusually warm or polluted waters, stressed corals expel these algae and expose their white skeletons, appearing bleached. “If the corals can’t recruit more symbiotic algae, they will be unable to sustain their metabolic needs and will become susceptible to disease,” Koss said.

Since 2014, stony coral tissue loss disease, the most pervasive coral disease outbreak on record, has spread up and down the Florida Reef and throughout the Caribbean. “It’s a pandemic,” Koss said. “The disease moves very quickly and kills multiple species.”

In December the outbreak reached Buck Island Reef National Monument, meaning that it is now ubiquitous around the two largest U.S. Virgin Islands, according to Nathaniel Hanna Holloway, a NPS biological science technician stationed in Saint Croix.

“The disease’s arrival did not come as a surprise, but it was still gut-wrenching and alarming,” Hanna Holloway said. Once stony coral tissue loss is observed, highly trained NPS divers apply an antibiotic ointment to the disease lesions. This treatment has been shown to be effective in saving some of the diseased corals.

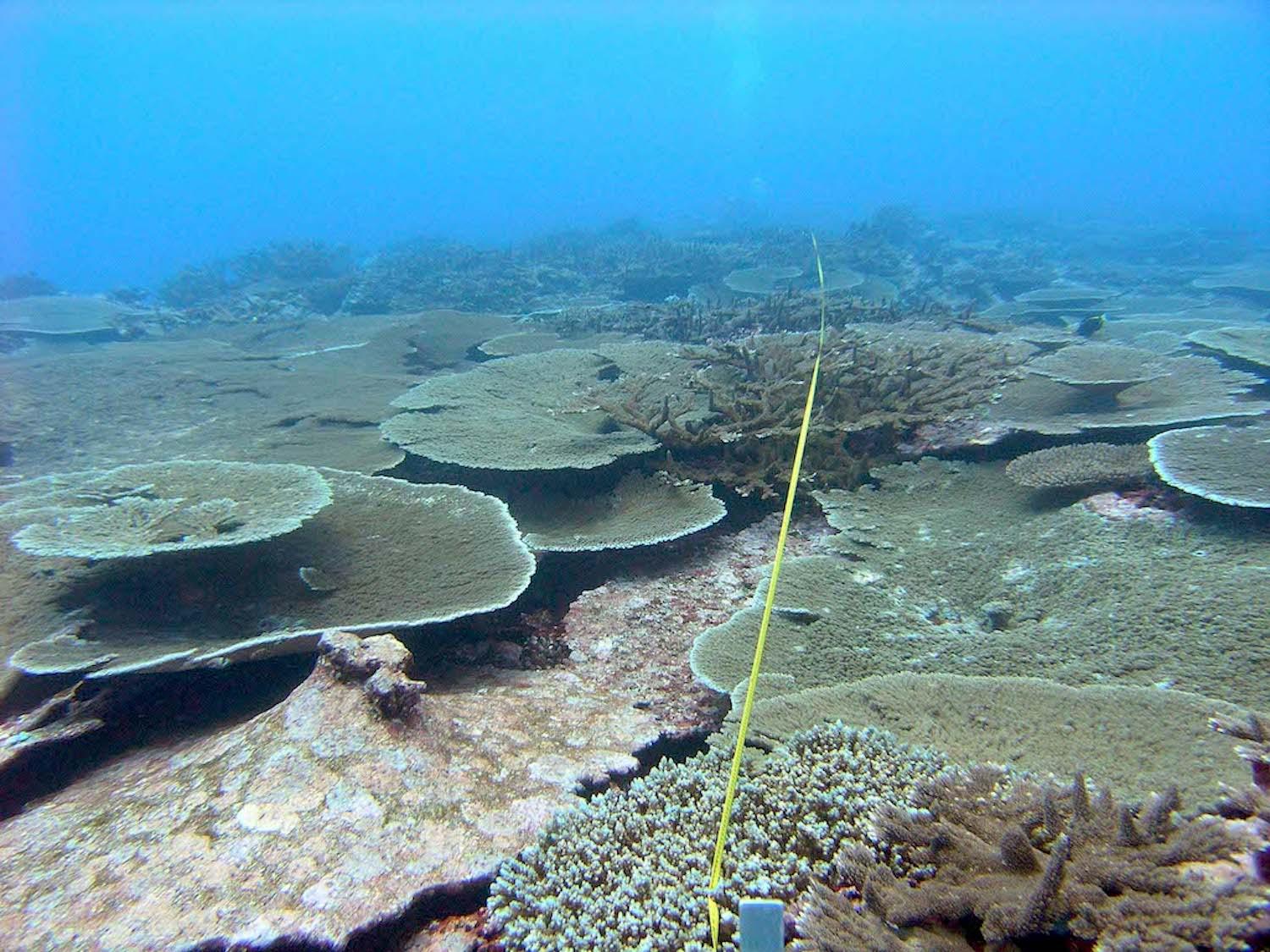

Before Cyclone Wilma hit a coral reef at National Park of American Samoa/NPS

After Cyclone Wilma hit National Park of American Samoa/NPS

NPS biological science technician Nathaniel Hanna Holloway applies an amoxicillin treatment to a coral with white plague, a similar affliction to stony coral tissue loss disease, in Buck Island Reef in February 2020/NPS, Kristen Ewen

For all the uncertainties about the future of coral reef parks, marine ecologists remain optimistic. “Reefs are vital, ancient structures that have formed over thousands of years,” said McLaughlin of the NPCA. “Hopefully, with the protection of the NPS and with support from Americans all over the country, reefs can survive thousands of years in the future and continue to provide for incredible wildlife and marine biodiversity.”

The NPS recommends that people interested in protecting coral reefs aim to reduce their carbon emissions. Divers and snorkelers who plan to visit a reef park should wear environmentally friendly sunscreen and always keep a safe distance from the corals.

Threatened Parks:

Biscayne National Park, Florida

Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands

Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida

Kaloko-Honokōhu National Historical Park, Hawai'i

Kalaupapa National Historical Park, Hawai'i

National Park of American Samoa, American Samoa

Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve, U.S. Virgin Islands

Virgin Islands National Park, U.S. Virgin Islands

Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands

Comments

Thanks for publishing this story. It is good to read that so many agencies and organizations have the same consensus - that our coral reefs are threatened and declining. Aside from identifying reefs as "protected", I wonder what the National Park Service can do proactively to help slow down the decline? For example, are any of the national parks listed doing coral planting or utilizing coral restoration techniques?