Not quite 10 miles east of Idaho 93 in southern Idaho, Minidoka National Historic Site is an appropriately somber destination, and not only for the dark chapter of American history it strives to explain.

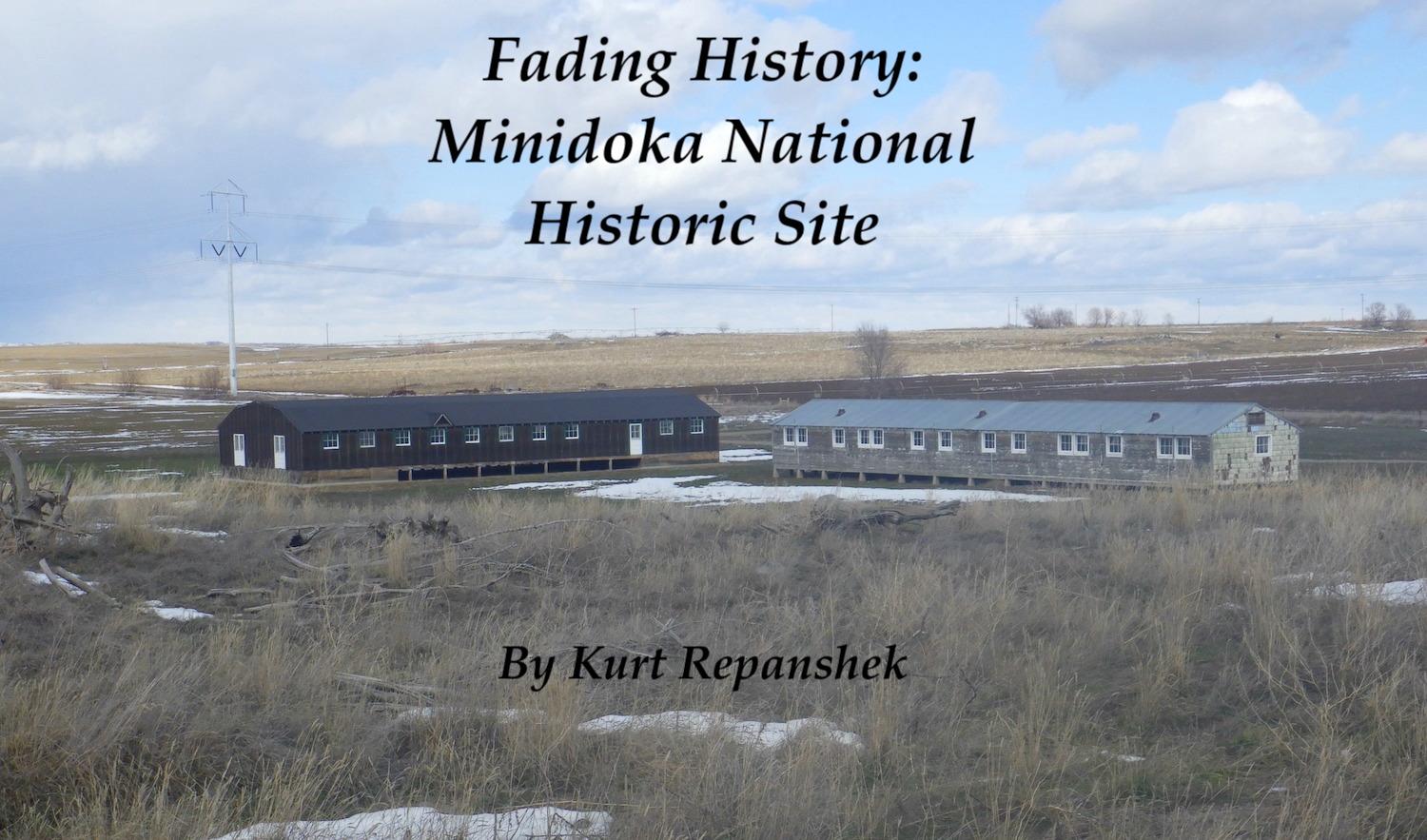

Squishing through the sodden ground of early spring to the lone barracks that remains from the 1940s, when there were more than 400 of the 120-foot by 20-foot structures, I stepped up onto the porch steps and peered through a dirty window. The darkened interior was bereft of any clue to just how miserable the living conditions were for the thousands of "Issei," first generation Japanese-Americans and their families who were forced by the federal government in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor to be hauled by train into the scrublands of the Snake River Plain from Washington and Oregon for incarceration because of the perceived threat they posed to the United States during World War II.

No furniture was in sight, just large support timbers to keep gusting winds from knocking down the building. Outside, the clapboard walls were desperate for paint. And because of how unevenly the National Park Service allocates funding, it doesn’t look like needed restoration work is forthcoming.

Minidoka is not unique in wanting for adequate funding to protect, and interpret, its history, but it's a clear example of the need that exists.

A Dark Chapter Of History

When it opened on August 10, 1942, the incarceration camp was located on 33,000 acres, though just 950 acres were used for administrative and residential purposes, with another 800 acres set aside for farming. The surrounding landscape was an affront to many of the Japanese-Americans who had been pulled from lush Washington and Oregon.

"The first thing that impressed me was the bareness of the land," said Shozo Kaneko in a 1943 interview. "There wasn't a tree in sight, not even a blade of green grass. Coming from the Northwest where there was a lot of green fields and forest, the sights staggered most of us who had never seen anything like that before."

At the height of World War II, the incarceration camp held hundreds of buildings: barracks for families, a hospital, tool shops, lavatory, gas station, pump house, laundry, men's and women's dormitories. Threaded through the site were paths to vegetable gardens, a poultry farm, and pig sty.

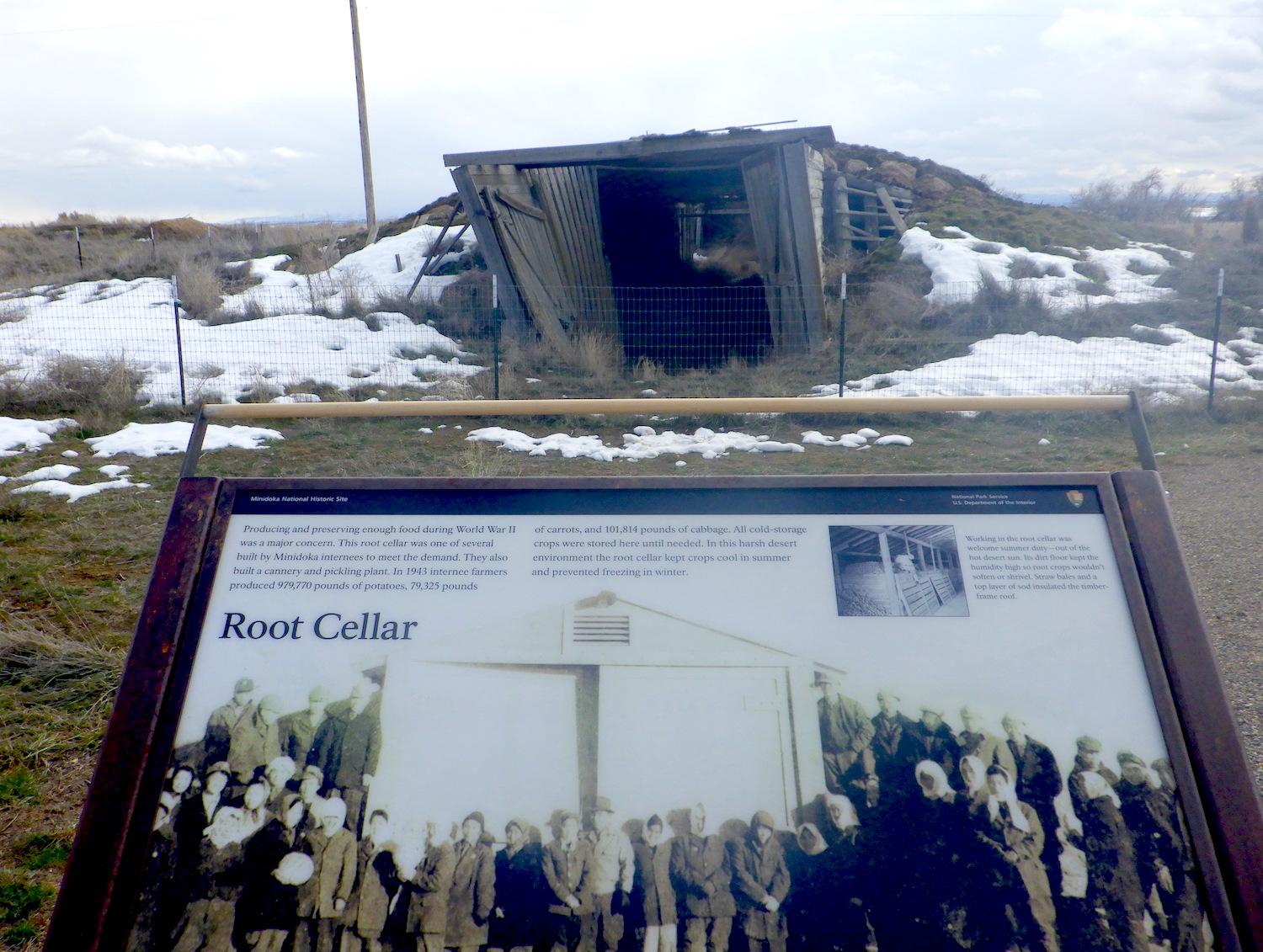

Today, most of the historic fabric that depicted a repugnant chapter of U.S. history has been erased by time. To the south of the barracks stands an enormous root cellar the incarcerees built to hold the onions, carrots, corn, tomatoes, potatoes, radishes, cucumbers and other produce they grew on plots to the east of the dozens of barracks to feed themselves. Sadly, it is in a slow-motion state of collapse.

Fading placards here and there along a 1.6-mile trail explain what you can't see, but they fail in comparison to being able to stand inside an uninsulated barracks next to a potbelly stove, an army cot, and simple furnishings that these Americans had to survive through the changing seasons. Darkness was broken by a single bare lightbulb in each room, outbuildings housed bathrooms, latrines, and laundry facilities.

You can stand in front of the root cellar and might envision the 50-foot-wide by 200-foot long storage chamber stocked with vegetables, but you can't walk inside that cellar to experience a moment in 1944.

A root cellar built by Japanese-Americans incarcerated at Minidoka National Historic Site is slowly eroding into the landscape/Kurt Repanshek

An interior shot of the root cellar, taken in 2019/NPS

Standing in the afternoon cold, under a leaden sky, I struggled to imagine life at Minidoka. it was a complicated task, for while the National Park Service's role at Minidoka is to interpret "[T]he history and cultural resources associated with the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans during World War II," that's not an easy job for the resource-strapped agency.

For Fiscal Year 2021, Congress provided $488,000 for Minidoka. In his FY2022 budget proposal, President Biden called for a $210,000 increase for the site; Congress provided a $12,000 bump. With your average Park Service employee costing the agency about $100,000 a year in salary and benefits, and utilities and routine maintenance, $500,000 doesn't go far at Minidoka, a sum that pays for 3.5 full-time employees, one whose job is focused on maintenance.

The Park Service did raise $7.5 million -- a cost that covered site preparation, construction, and exhibits -- for a new visitor center that opened two years ago, but it was closed during my visit. It's typically closed during the winter months, for lack of resources and probably for lack of visitors. Last year the park counted a few more than 15,000 (just 86 in December) visitors, in 2020 just 6,747, and in 2019 the tally was 13,647.

On that cold March day, I was joined by my wife, and two men who paused for photos at the remnants of the stone guard station at the park entrance and drove off.

Is Minidoka's FY 2022 $500,000 annual budget reasonable? At least seven other units of the Park System that were established between 1999 and 2006 had greater budgets in FY21, when Minidoka's was right around $488,000: Minuteman Missile National Historic Site (established 1999, $3,296,000 budget); Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park (2000, $1,362,000); Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument (2001, $497,000); Governors Island National Monument (2001, $1,582,000; Flight 93 National Memorial (2002, $1,688,000); Cedar Creek & Belle Grove National Historical Park (2002, $925,000); and African Burial Ground National Monument (2006, $1,389,000).

Can You Find Minidoka?

Of course, you need to be aware of Minidoka, which shares its name with the county it's located in and which is thought to descend from the Shoshone Indian word for "broad expanse," before you can go in search of it. I had to resort to my phone's mapping program. No signs on Interstate 86 that funnels millions of vehicles across southern Idaho less than a half-hour from the historic site mention it, nor do any on Idaho 93 despite the fact that at its inglorious height Minidoka housed nearly 10,000 Americans, an astonishing historical tragedy that we shouldn't forget and which deserves robust interpretation. They included artists, writers, poets, craftsmen, scientists, doctors, lawyers, former mobsters, and even a young man who went on to fight, and die, for the United States in Europe and who posthumously was awarded the Medal of Honor.

And yet, while there is a great lack of interpretive materials at Minidoka -- the archaeological collection from the park actually is stored at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument not quite 40 miles to the west -- the park has come a long way during the past 20 years, Dan Sakura, who runs a conservation consulting agency working with Friends of Minidoka, told me during a phone call along with Robyn Achilles, the friends group's executive director.

"I've worked very hard to bring the park up to what it is today. It's been 20 years of effort to ensure that the park is a place for healing and learning," said Sakura, whose parents, grandparents, and great-grandmother were incarcerated at Minidoka.

Some of the money the friends group and Sakura were able to raise was spent on replicating one of the eight wooden guard towers that once stood over the camp. Achilles agreed with Sakura on how far Minidoka has come from when the Park Service acquired it in 2001.

In 2014 a Friends of Minidoka project with help from Boise State University students built a replica guard tower that stands at the park entrance/Kurt Repanshek

"It's pretty amazing what they have been able to accomplish on the park," said Achilles, who just recently came to the friends group. "It was nothing. There wasn't anything there. Friends of Minidoka, the nonprofit partner, they were able to rebuild the military honor roll, the guard tower [in 2014 with help from Boise State University students], they also helped build the baseball field.

"It's pretty remarkable. People call Minidoka a gem of the confinement sites," she continued. "I mean, each one has its own flavor and different things that are special about it. But Minidoka, people often say is a gem."

Achilles pointed out that the lone barracks and neighboring mess hall that stand in a field not far from the visitor center were not there when the Park Service acquired the site, but had to be relocated to that area.

"They still have work to do, for sure," she said. "They would like to restore some of the buildings. There's always more work to do. But like Dan said, we are pretty thankful for what has been created so far."

What Stood Here?

And yet, Minidoka could be held up as a prime example of how Congress is quick to add units to the National Park System but doesn't follow through with the necessary funding to maintain them and, in the case of Minidoka, truly interpret the history that justified the site's addition to the park system.

"The story of what happened in the Japanese-American community is painful. I had three generations of my family there. But what's inspiring about it is the courage and the sacrifice that Japanese-Americans made," Sakura weighed in, noting the honor roll near the park entrance that commemorates those who left the camp to fight for the United States in the war. "We're proud of the significant investments that the community and the Park Service have made in Minidoka through the general management planning process, which was completed in 2006, the land acquisition, the purchase of the farm-in-a-day property, the visitor center. Really remarkable accomplishments."

From his point of view, Sakura sees Minidoka National Historic Site as a child of sorts.

"Creating parks is like having children. And, you know, the fun part is the proclamation, the bill signing, the establishment," he pointed out. "And then you've got the real hard work. It's like changing diapers and taking out the garbage. It's a lot of hard work, particularly infant parks, you know, when they're just getting started. They need a lot of effort. Minidoka has marched up the learning curve. I would say Minidoka is a young adult now."

At a time when National Park Service Director Chuck Sams is urging visitors to the National Park System to go beyond the top 25 or so name-brand parks, and when U.S. senators are worried about overcrowding in some areas of the park system and believe greater efforts need to be made to "encourage visitation to all of our national park units," there's a lack of financial commitment to give the traveling public a reason to visit Minidoka and other units not named Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Acadia, Zion or Yosemite.

Standing in front of the root cellar, I wondered if not too far in the distant future, because of a lack of funding, all that will remain will be a placard with a photo of the cellar when it was built with wording to the effect of, "A root cellar once stood here."

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

This isn't all a funding question. It is also about expectation management. It is a lot easier to create a new unit (no matter the story preserved) than to run a unit. As soon as a new unit is created there is a rush to bring a similar structure of other units (a Supt, a chief of this and that), a visitor center, a collection, maintenance facility, housing, etc etc etc. Why? Because that is what every other unit has or is asking for and "we must have it to". The NPS must get a bit more innovative in what it is doing across the country. It is always easy to say it is lack of funding as that claim drives and fuels advocacy. . It is much harder to say the problem might be, in part, how the agency is organized and runs itself and it's inability to learn as an organization. The NPS lacks funding no doubt. Always has, and always will.

Thr NPS lacks is the ability to provide adequate expectation management - internally and externally. That is something that can be learned if given the space to manage expectations. Any person who is an outlier or change agent in the system who pushes the envelope - whether fees charged, reservations, reservation systems, partnerships, a more business outlook on operational and investment decisions, etc is immediately subjected to complaints, congressional inquiries, or the wrath of advocacy organizations. It is amazing how quickly change can be reversed when folks reach into the politicals at DOI - but is is shocking how long change takes to get to a decision and implementation. Unfortunately, this atmosphere breeds not only a fear of failure among Carew leadership - but also a fear of trying to solve long standing problems. This happens all the way up the chain -- no matter what party is in power at DOI.

As someone who has worked in multiple parks in development, I wonder what "expectations management" means?

It sounds like you want a park without staff and that to become the norm. Every park in development I worked at had a robust interpretive staff for a reason--this new park needs it. Minidoka is clearly not getting that and the reason is budgetary.