Editor's note: Volcano Watch is a weekly article and activity update written by U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates.

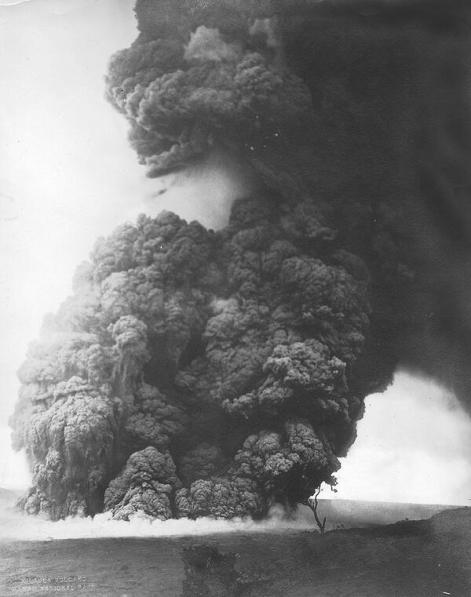

Kīlauea began erupting explosively at Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park 100 years ago this week, for the first time in nearly a century. The eruption lasted for about 17 days, killing one person and injuring others.

At Kīlauea’s summit, the floor of Halemaʻumaʻu began dropping on or before April 29 and was lower by 328 ft (100 m) on May 7, the last measurement date. Rock falls from the crater wall generated thick dust clouds. Red-hot “ʻaʻā paste” left over from the drained lava lake peeled away from the wall, but observers noted no wholesale collapse.

The first explosion was unobserved during the night of May 10–11 and ejected blocks weighing more than 330 pounds (150 kg) as far as 200 ft (60 m) from the crater. After relative calm on May 11–12, the eruption took off in earnest on May 13. Thereafter, more than 50 distinct explosions occurred until May 27, when the eruption ended.

Thousands of rocks were tossed high in the air, littering the caldera floor. Intense electrical storms accompanied some of the explosions, and lightning took out powerlines far down the road to Hilo. Earthquakes shook the ground, and mud rains with pellets the size of peas (called accretionary lapilli) pummeled the summit. Blocks weighing several tons landed more than half a mile (1 km) from the crater; one 8-ton block that landed about a mile (2 km) southeast of the crater became a signed visitor site for many years, even surviving the caldera collapse of 2018.

The explosive crescendo was on Sunday, May 18, when the two largest explosions occurred. A number of observers were on the caldera floor during the first, and one, Truman Taylor, was fatally injured by a falling rock. By remarkable coincidence, 56 years later the devastating eruption of Mount Saint Helens occurred on Sunday, May 18, 1980, and both eruptions killed a man named Truman. Truth is sometimes stranger than fiction.

Most of the ash from the explosions was blown southwestward by the trade wind, but some, perhaps supplied by higher eruption columns that overtopped the trade wind regime, fell from South Hilo to lower Puna. Railroad travel in Makuʻu was disrupted when the tracks became slippery from wet ash. Rain washed ash from the roof of the Glenwood store, tearing off the gutters. Overall, though, the production of ash was modest, and, after only 20 years, it was hard to find ash deposits outside the caldera, as wind and water swept them away.

During the eruption, Halemaʻumaʻu doubled its diameter to about half a mile (1 km), and its floor dropped more than 1640 ft (500 m).

What powered the explosions? For years the interpretation was that they resulted from steam explosions generated as groundwater encountered hot rock. This interpretation, suggested at the time, served well until the 2018 collapse of Halemaʻumaʻu and the adjacent caldera produced nothing comparable to the 1924 explosions.

Theoretical modeling indicates that months to years are required for the conduit wall to cool enough for groundwater to return after draining of a lava lake. Is there any way to overcome this theoretical requirement? What role did magmatic gas—dissolved in magma and released explosively by sudden drop in pressure—play in 1924 or in 2018? Ongoing work by USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) researchers on the 1924 ash is providing new information bearing on these questions. Next week’s “Volcano Watch” article will describe this research.

Finally, a sad, deeply personal, note. Thomas Jaggar, esteemed head of HVO, was in New York when the eruption started, not returning home to Hawaii until May 28. In a private letter written 23 years later, he lamented "...1924 was my responsibility, and my absence was a pity, the most fatal disappointment of my life."

On Tuesday, May 14 at 7 p.m., join Don Swanson, HVO geologist emeritus, and Ben Gaddis, HVO volunteer, as they describe the 1924 explosive eruption of Kīlauea in an After Dark in the Park presentation at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. Park entrance fees apply. See here for more information: https://www.nps.gov/havo/learn/news/20240329_may-2024-events.htm. This program will be repeated on May 20 and 21 at Lyman Museum in Hilo. See here for more information: https://lymanmuseum.org/events/.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places