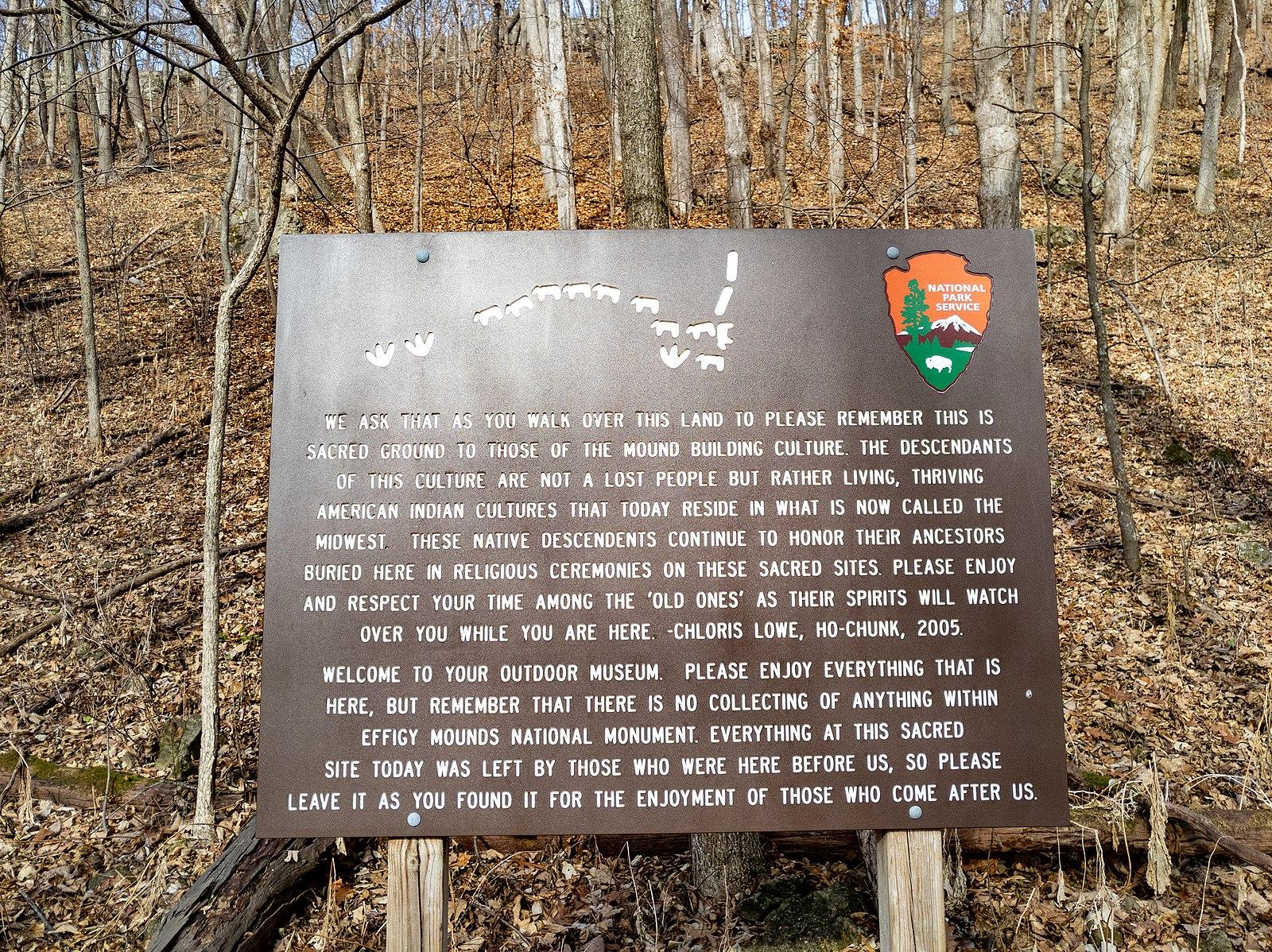

More than 2,000 years ago, Indigenous North Americans began building large earthen mounds next to the Upper Mississippi River near what is now the border separating Iowa and Wisconsin. Some were burial mounds, subdued in design and conical shaped. Some were ceremonial, taking the shape of animals sacred to the builders. They continued building for thousands of years, with the last known mound erected about 700 years ago.

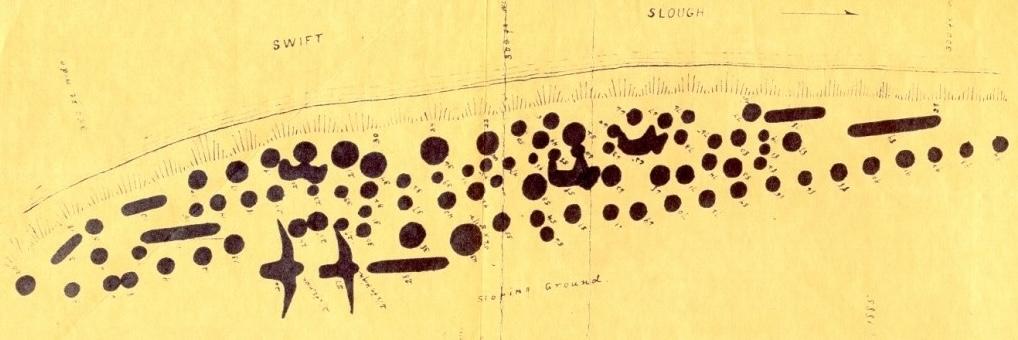

Today, the mounds are managed and preserved as part of Effigy Mounds National Monument, on the west side of the river, about 10 miles south of Harper's Ferry, Iowa. There are more than 200 mounds in the monument, with the largest concentration of mounds within the Sny Magill Unit. It's one of the most densely clustered concentration of such mounds in North America.

The Sny Magill mounds are not like their more famous cousins in Cahokia, huge blocks of earth shapped like the bases of ziggurats, further south and west in Illinois. Walking among the Sny Magill mounds, they almost appear natural parts of the landscape. Perhaps they were engineered that way on purpose.

They're burial mounds, generally oval or circular in shape. They're not particularly tall, most just a few feet in height. The mounds are covered in grasses and surrounded by trees, like rows of small, undulating hills, or large ski moguls.

Portion of a historic Map of Sny Magill Mound Group drawn by T. H. Lewis / NPS

Effigy Mounds National Monument lies within a topographically and geologically fascinating area called the Driftless Zone. Composed of hills, spring-fed creeks spilling over waterfalls, tree-lined ridges, and steep bluffs overlooking a broad sandy floodplain of the Mississippi, it looks less like the Midwest, and more like the forested wilderness you'd find further north in the boreal forests above the Great Lakes, or a picturesque stretch of New England.

The mound builders chose this location to live and erect their mounds because they had a deep connection to the land and the life-giving Mississippi that flowed between the bluffs, alongside their villages and mounds.

“The area itself is part of our homeland,” Sunshine Thomas Bear, tribal historic preservation officer for the Winnebago Nation of Nebraska, a descendent of the mound builders, told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “Our connection to these lands goes back thousands of years."

But now, the Mississippi itself is threatening those mounds with erosion.

Effigy Mounds signage / Wikipedia

For years, the river has chewed at the riverbank the mounds are built on, with the mounds closest to the river already being eroded away in increasingly bigger chunks. The area is prone to seasonal flooding when the Mississippi rises each year; it is a floodplain after all.

But in recent decades, the Upper Mississippi has become wetter, with more high water days, increased flooding, and generally speaking, more water moving through the river system, according to research conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey, Department of the Interior, Army Corps of Engineers, and Upper Mississippi River Basin Association.

Longer, heavier storms due to climate change is one factor, as is river management. A series of locks and dams on the Upper Mississippi built nearly a century ago, as well as infrastructure built along the river, have contributed to increased flows and greater discharge throughout the river.

More water moving through the river system and more flooding has not only meant a loss in forest cover, but changing erosion patterns, with significant bank scouring happening in low-lying places like the Sny Magill Unit.

Officials at Effigy Mounds National Monument have tried piecemeal solutions to stabilize the bank since at least the 1980s, when they first began noticing the erosion, but each successive attempt was washed away with increasing waters.

View of the Mississippi River from Fire Point, with Effigy Mounds National Monument on the right / NPS

Now, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has a plan for a semi-permanent solution.

After consulting with the NPS and local tribal leaders, the Army Corps' plan is a massive rock berm, 2,000 feet long, made of boulders, with a backing wall of sand dredged from the river's main channel. The hope is this berm would act as a retaining wall between the mounds and an increasingly temperamental river. As the river rises, it will meet the berm, which will be the same height as the floodplain, so it should hold back even the biggest floods. In theory.

It's a far more complicated and costly potential fix than anything tried before, but the berm has been designed with future floods in mind.

Screenshot of the plans for the rock berm to protect the mounds / US Army Corps of Engineers

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment