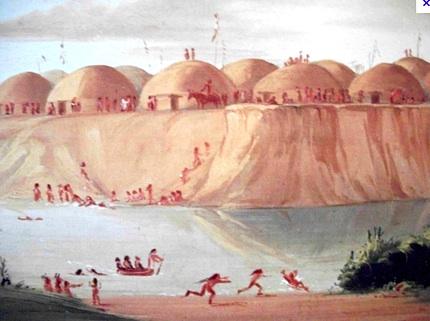

Paddling the lazy flows of the Knife River, our approach to the Indian village that sent a young Indian woman west with Lewis and Clark could have been a day out of the past.

It was early June, and already the river was sluggish, more a reflection of the dry winter rather than the normal flow. River banks rose high above on both shores, initially hiding a finger of what was the heart of trading on the Northern Plains in the early 1800s.

Cottonwoods reach out over the river, and there are green ash and willows. Beyond the banks, mixed-grass prairie runs, much like it did when Meriwether Lewis and Willam Clark arrived in the fall of 1804. When they reached here after having traveled roughly 1,600 miles up the Missouri River from St. Louis winter was in the air, and the explorers decided to build a fort here near the Indian villages and sit out the winter.

Ready to greet them was a chain of Indian villages that held not just Mandan and Hidasta, but a variety of tribes as well as white traders.

At trading time, in the late summer, the river villages were crowded with Crows, Assiniboines, Cheyennes, Kiowas, Arapahoes, along with whites from the North West Company, the Hudson's Bay company, and St. Louis businessmen.

Nowhere else could one see at a single glance the diversity and colorful life style of the Indians of the Plains. There were Spanish horses and mules to buy and sell, fancy Cheyenne leather clothing, English trade guns, baskets of produce, meat products, furs of all kinds, musical instruments, blankets, dressed buffalo hides, painted buffalo hides. During the fair there was dancing until well into the night, and much visiting back and forth, and competition between the boys. It was a grand time in the five villages. -- Stephen E. Ambrose in Undaunted Courage.

The earthlodge behind the visitor center at Knife River Indian Villages NHS. Kurt Repanshek photo.

During their winter along the Knife River, Lewis and Clark met Toussaint Charbonneau, "a French-Canadian trader who had been living with the Hidatsa," according to park historians. He asked whether the two needed an interpreter on their trek west, and along with him they also took on his wife, Sakakawea (Sacagewea), a member of the Shoshone tribe who was seen as invaluable to Lewis and Clark for her language skills.

Footprints From The Past

Today, birds calling and leaves fluttering in the breezes welcome you to Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site. It's a bit off the well-traveled path, roughly an hour by car north of Bismarck, North Dakota, next to the small town of Stanton. But it's a sidetrip well worth it if frontier or Native American history interests you.

In the relative silence behind the visitor center, the vestiges of those sprawling villages rumple the prairie before you. Dozens of mounds, all that's left of the dense clusters of earthlodges that greeted Lewis and Clark, ripple the prairie. Dotting many of the mounds are smaller piles of dirt kicked up by gophers and other burrow-dwellers that are quite literally digging into the past.

"This to me is really where the park comes alive," Wendy Ross, the Knife River superintendent, tells me as we walk among the mounds and stop to inspect the bits of flint, bone, even bison molars, the rodents have pushed to the surface. They are artifacts from the days when the Indian villages were thought to have a combined population greater than that of St. Louis.

"These are physical spaces," adds Stephen Bridenstine, a seasonal interpretive ranger who joined us on our walk. "People lived and died here."

Ranger Lori Nohner explains what's to be found inside the earthlodge at Knife River Indian Villages NHS. Kurt Repanshek photo.

Stop, close your eyes, and you can envision the past without much difficulty. Two hundred years ago, Bridenstine continues, dog barks filled the air along with the songs from women tending their crops and kids darted about through the maze of earthlodges.

You get a more realistic sense of the past by entering an earthlodge replica that was built in 1994 just behind the park's visitor center. Massive cottonwood trunks serve as the primary foundation, anchored deep in the earth and rising up from the lodge's center. Cottonwood limbs serve as beams that were interwoven with willow branches before the final layer of dirt was applied.

In general, Ranger Lori Nohner tells a small group of us gathered inside the lodge, it would take the tribes 7-10 days to build a lodge that might be 45 feet in diameter and large enough to shelter 10-15 people, and even their prized ponies.

Entryways feature a small vestibule that includes a small fence of stout poles in front of which a bison skin is suspended to block cold air. A fire pit takes up the very middle of the lodge. Off to one side stands a small sweat lodge, while sleeping bunks covered with bison skins run along the walls. Small cache pits, perhaps 4 feet deep, were used to keep foods cool in the summer heat.

Laid out around the earthlodge are artifacts that reflect on tribal life of two centuries ago: a knife honed out of a bison scapula, a flute with a duck head through which the notes flowed, a goose-feather fan, drums, bison robes, baskets and bowls, even spears.

Agrarian Culture

On the river bottoms below the villages the tribes would grow their gardens in the rich soils.

A table at one of the earthlodges at On-A-Slant-Village at Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park near Bismarck shows off a sampling of vegetables the tribes would grow. Kurt Repanshek photo.

In small mounds of that soil women, armed with hoes made from bison scapulas, would plant corn in the middle of the mound, surround it with a type of pole bean that would wrap itself around the corn stalks as it grew, and then squash that would spread out with its massive leaves that would act as a mulch to both keep down weeds and hold in moisture. Also rising from the bottomlands were sunflowers and tobacco.

Small scaffolds stood next to the gardens, and up onto them young girls would climb to watch over the vegetables and shoo off birds as well as four- and two-legged intruders.

Archaeological work has turned up artifacts that date to as far back as 11,000 years before the present. The Hidatsa, though, probably didn't arrive on scene until 1300 or so, according to park historians. But once they arrived, they stayed, as the evidence points to 500 years of continued habitation here along the Knife River.

Exploring Knife River

The small visitor center itself is rich with artifacts and a short, 15-minute orientation film that traces the life of Maxidiwiac, or Buffalo Bird Women, a Hidatsa born along the Knife River about 1840 whose stories were handed down through interviews recorded by an anthropoligist who lived with Hidatsa, Mandan and Arikara in the early 1900s.

After visiting the earthlodge, you can walk the Village Trail that leads you out to the center of where one of the Indian villages stood in 1804. Along the way you rise and fall along the mounded terraces that show where earthlodges once stood. You also can stoop and see what the gophers and ground squirrels have brought to sunlight (but remember, don't remove anything you see). The Village Trail also allows you to tie into the Two Rivers Trail that leads you along the top of the riverbank, and even down to the riverbank itself, for views of the Knife River.

On-A-Slant Village at Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park. Photo by Jason Lindsey for North Dakota Tourism.

To reach the third trail at the historic site, the North Forest Trail, you need to drive a short distance north of the Visitor Center. This trail leads you to the Big Hidatsa village site that was established about 1600. The trail then winds through the forest, where the villagers would move into in winter to gain some respite from the cold winds, and edges out to the Missouri River.

You can rush through Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site in as little as an hour, but that would deprive you of insights into the cultures that lived here for centuries. Take your time. Soak in the atmosphere. And don't ignore the site in winter, when fires sometimes are crackling inside the earthlodge and interpreters are cooking meals for you to sample.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Knife River is one of those little gems that comprise much of the national park system. When I was there in August 2009, I was the only visitor in the place. Besides the park itself, the drive through that part of North Dakota is incredibly scenic. It's located in an area that will fascinate any geologist with its great display of moraine features left over from the end of the Pleistocene ice age. The small towns along the way are filled with terrifically friendly people and, if you look for them, little museums where you can spend a delightful morning or afternoon. (Just be careful, because you'll completely destroy any schedule you may be trying to keep.)

Fort Mandan state park is not far to the east of Knife River. It's a must stop, too.

Thanks for another great article, Kurt.

Dang,my bucket list just keeps getting longer and longer!!