The island of Maui, Hawaii, upon which sits Haleakalā National Park, has the same geologic origin as Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island of Hawaii. This is because Maui, like the Big Island, is the result of plate tectonics and a “hot spot.”

The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago – a group of islands within a body of water like the ocean or a lake. What you see when you fly over these archipelago islands are actually the tips of mountains – the exposed peaks of the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount chain. That’s right, when you hike within this national park, you are hiking over the top of a mountain, the bulk of which is below sea level. And, it’s taken about 70 million years to create this seamount chain and the tropical paradise you see today.

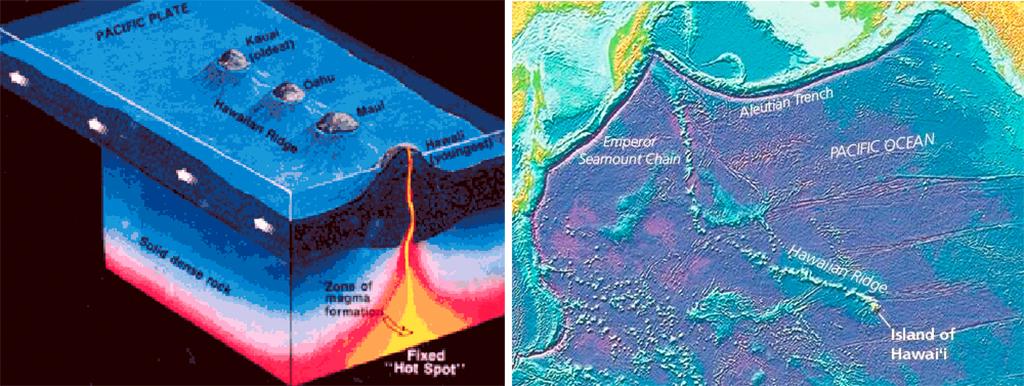

The creation and location of the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount chain, Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park / USGS-NPS

The Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount chain extends over 3,700 miles (5,954.6 km) and is the result of hot spot volcanism. A hot spot is a plume of localized high heat energy that remains in place while plate tectonics shift above it. The hot spot creates volcanic eruptions which overlap each other and build up toward, and above, the sea. Picture a conveyor belt. This plume of heat energy remains stationary while the plates (the conveyor belt) continue moving. As long as there is continued heat and magma from that hot spot, more submarine mountains resulting in islands are formed until the heat finally cools or is diverted elsewhere. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the Pacific Plate, upon which sit the Hawaiian Islands, moves an estimated 2–4 inches (6-10 cm) per year.

As the plates move the islands in this chain away from that stationary hot spot, the volcanoes on that island become less active since the heat source has been removed. Kauai is the oldest island in this chain, and the Big Island of Hawai’i is the youngest, still over that hot spot and still volcanically active.

Maui is the next youngest island. Created by eruptions and lava flows from two volcanoes – Haleakalā on East Maui and Mauna Kahalawai on West Maui. Both volcanoes are eroded shield volcanoes, composed from the gradual buildup of many thin layers of lava to create a shape like a warrior’s shield —long, broad, and gently curved.

A view of Haleakalā's valley filled with pu'u (cinder cones), Haleakalā National Park / Steven Walter via NPS

According to park staff

The shape of Haleakalā means that only the very top — only about 5 percent — is above sea level. The summit of Haleakalā currently stands at 10,023 feet (3,055 meters), but is believed to have once reached 15,000 feet (4,572 meters) above sea level. Erosion has worked heavily upon Haleakalā and it is so heavy it has also begun to sink into the crust of the Earth. Even with this loss in height, however, the volcano stands 28,000 feet (8,534 meters) above the sea floor, making it the third-tallest mountain on Earth.

When you look down into Haleakalā’s depths, you can count 14 different cinder cones, or puʻu. These formed when explosive volcanic eruptions ejected cinder and scoria that rapidly cooled and fell around the eruption vent, accumulating into a cone-shaped hill.

Crater Or Volcanic Valley?

The V-shaped valley of Haleakalā partially filled by lava flows and cinder cones, Haleakalā National Park / David Schoonover via NPS

You may notice in some of these articles the words “crater” and “valley” being used interchangeably when describing the floor of Haleakalā volcano. But which is it?

According to park staff:

What some call “the crater” is actually a massive valley carved by water and landslides. The original circular crater of the summit is long eroded away. The current S-shaped valley near the summit of the mountain is 3,000 feet (914 meters) at its deepest and about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) at its widest. This vast valley was once twice as deep, but subsequent eruptions of Haleakalā partially filled the valley with flows and cinder cones.

It's still OK to call it a crater when describing this volcano, but know that it’s really a valley.

Haleakalā Fun Facts From Park Staff

- Haleakalā actually rose .23 feet (.07 meters) per year between 1981 and 1992. Satellites measured this change, and geologists theorized that it could have been due either to the movement of magma (lava that has not erupted yet) deep under the sea floor or as a reaction to the ongoing eruptions on Hawaiʻi Island. Constant eruptions on Hawaiʻi Island added mass to the island and caused it to sink, forcing Maui to rise up as a reaction, similar to when a person sits next to you on a couch and causes your cushion to push you up a bit.

- Shield volcanoes like Haleakalā form where there are hotspots in the earth’s crust. Their lava is thin and flows easily. Composite volcanoes like Vesuvius or Mount St. Helens typically form where plates come together. Their lava is thicker and doesn’t flow easily so these volcanoes tend to explode a mix (a “composite”) of lava, rock, and ash.

- From Kahului, look back at Haleakalā. The rows of puʻu you see on both sides of the volcano mark “rift zones” — long lines of stress fractures on the flanks of the volcano where eruptions can occur. The last eruption on Maui occurred on the southwest flank of Haleakalā, along the southwest rift zone near Wailea. Because the volcano is not yet extinct, this rift zone could be the location of a future eruption.

- Lava comes from the Italian word lavare, “to wash.” Originally referring to a stream formed by sudden rain, the term was also applied to the streams of molten lava coming down from Mount Vesuvius.

- It is a common practice for geologic forms to be named after the place where they were first described or where the best examples are found. Local names for these formations are also used, such as “Pāhoehoe” and “ ʻAʻā.”

- Pāhoehoe is a combination of Hawaiian words: pā, for stone wall and hoe, for paddling a canoe. The combination can refer to the ripples of stone often seen as this type of lava flows and cools.

- ʻAʻā is a Hawaiian word that can refer to burning, blazing, or glowing.

You’ll see both types of lava during a visit to Haleakalā National Park.