The archaeology of Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska is rewarding and frustrating at the same time.

A reconstructed traditional semi-subterranean home dating back to AD 1200 – 1300 to which park visitors can view just a short walk from Brooks Camp in Katmai National Park and Preserve / Rebecca Latson

Archaeology studies material remains of the past. Unfortunately, Katmai’s soils are acidic, so tangible softer artifacts such as nets, clothing, and baskets that could tell us about the people living and roaming within the region, dissolved over time because of those acids. What remains, however, in the form of projectile points, stone tools, etched stones, camps and cabins, have given archaeologists enough evidence to name five different traditions within the region dating back 9,000 years.

Traditions

We generally think of traditions as a practice handed down over the years, from family to family, usually around holidays, right? Archeological traditions are only slightly different: a group of people who share similar technology, subsistence practices, and socio-political organization over a large area and a long period of time.

The Paleoarctic Tradition – 9,000 to 7,000 years ago

Found across Alaska, this tradition represents the oldest sites found in Katmai. It is thought the people inhabiting the area arrived by foot over the Bering land bridge or by boat across the Bering Sea.

The Northern Archaic Tradition – 5,000 to 3,850 years ago

Forest-dwelling peoples living in the south, such as Canada, began migrating up into the Katmai area as forests spread north due to a warming climate.

The Arctic Small Tool Tradition – 3,850 to 3,000 years ago

While this tradition is found across Canada and Alaska, in Katmai, it’s found in the Naknek drainage. The people of this time used small, finely-chipped stone tools and lived in the earliest semi-subterranean houses that archeologists have found in the Katmai area.

The Norton Tradition – 2,250 to 900 years ago

This is the start of ceramic manufacturing as well as the first time it’s noticed the same people are living in both the Naknek drainage and the Katmai coast. Communities were becoming more settled but were not permanent year-round. People still moved seasonally to camps. However, they continually returned to the same locations rather than set up camps in new areas. Norton people are the first to intensively harvest salmon runs.

The Thule Tradition – 900 years ago to historic contact

During the Thule Tradition, people brought a sea mammal-hunting culture from western Alaska eastward as far as Greenland. Some archeologists think that the success of Thule people was due to falling temperatures which increased the pack ice, from which sea mammals are typically hunted. From the coasts, they spread inland, bearing artifacts of ground slate and building large semi-subterranean houses. Thule sites are found across the Katmai region.

Today, visitors to Brooks Camp and Brooks Lodge can view some of that archaeology for themselves, by walking the short 0.1-mile (.16 km) Cultural Site Trail to a reconstructed traditional semi-subterranean home dating back to AD 1200 – 1300, known as a barabara (from the Russian word barabóra). Brooks Camp is part of the Brooks River National Historic Landmark, which has one of the highest concentrations of prehistoric human dwellings in North America. Over 900 depressions, indicating the remains of semi-subterranean homes and campsites, line both sides of Brooks River.

The Fure Cabin

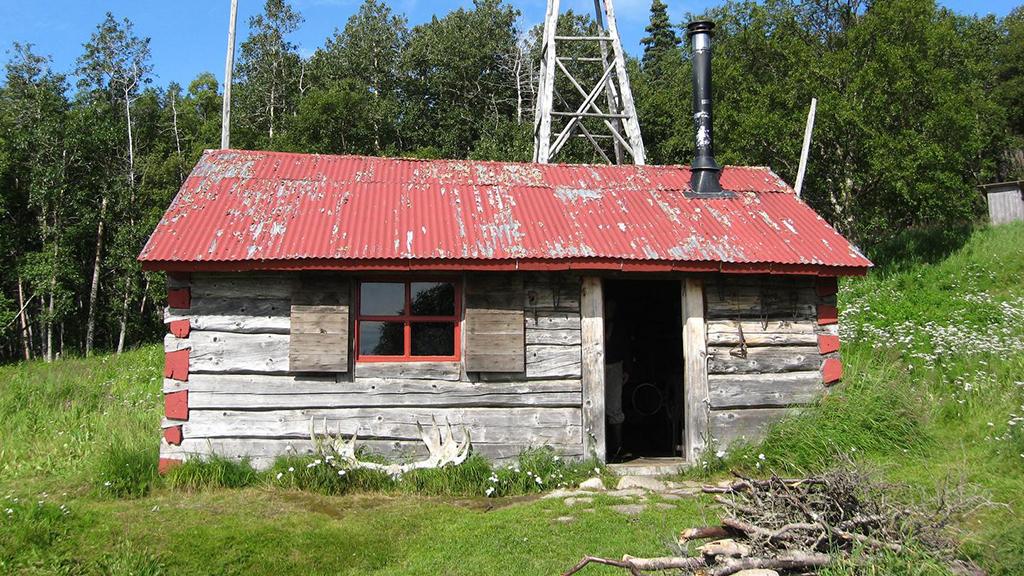

Roy Fure's cabin on Naknek Lake's Bay of Islands, Katmai National Park and Preserve / NPS file

There are other historic sites dotting Katmai that are old enough (50+ years) to be considered eligible as archaeological sites. They consist of cabins, camps, caches, military sites, and canneries.

One of these historic sites is the Fure Cabin, a restored one-room house on Naknek Lake's Bay of Islands built by trapper, miner, and famed Naknek local Roy Fure, and now available for public use.

According to Park staff:

Fure was born in 1885 in Lithuania, and came to Alaska in the early 1900s seeking his fortune. He settled in the Naknek area, supplementing his trapping and mining income by working as a laborer. In 1919, he married Anna Johnson, a Native woman from Bethel. They had three sons and a daughter, but only two of the children, Alexander and Marian, survived childhood. After Anna's death in 1929, Fure married Fanny Olson, a Native Alaskan woman from Naknek. They had a daughter, Nola, in 1930. Fanny left some time after 1940 for Kodiak.

The Bay of Islands cabin was built in 1926. The roof, walls, and floor are made of hand-hewn spruce logs with dovetail notching reminiscent of European craftsmanship. In 1931, the land on which the cabin stands was incorporated into the expanded Katmai National Monument.

Because he never became a U.S. citizen, Fure was not eligible for a homestead claim and was "trespassing" on Park land. In 1940, Fure was arrested for game violations and told to leave the Bay of Islands cabin. He and Fanny built a new cabin outside the Monument on American Creek, but continued to use the Bay of Islands cabin. Fure periodically stayed in the cabin until the 1950s. He died in 1962 in Portland, Oregon.

Fure's cabin was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. In the late 1980s, NPS maintenance staff restored the cabin.

The Fure cabin is now available for public use by hikers, kayakers, and canoers for $45 per night June 1 through September 17 and $22.50 per night outside of peak season. Guests at Fure’s cabin are limited to no more than four consecutive nights and seven nights per calendar year. Group size is limited to six. Discount passes are not valid for Fure’s Cabin reservations.

Current year reservations for Fure’s Cabin can normally be made starting January 5 at 8 AM Alaska Time and operate on a 6-month rolling basis. Visit www.recreation.gov to make a reservation.