Lassen Volcanic National Park in California is nothing if not dynamic. Every rock you see at Lassen is volcanic. Volcanic landforms – some glacially sculpted - and active hydrothermal features cover 170 square miles (430 sq. km) of the park. As a matter of fact, the desire to preserve these unique volcanic features was the primary reason for combining Lassen landscape with the two existing national monuments (Cinder Cone and Lassen Peak) to establish this national park in 1916.

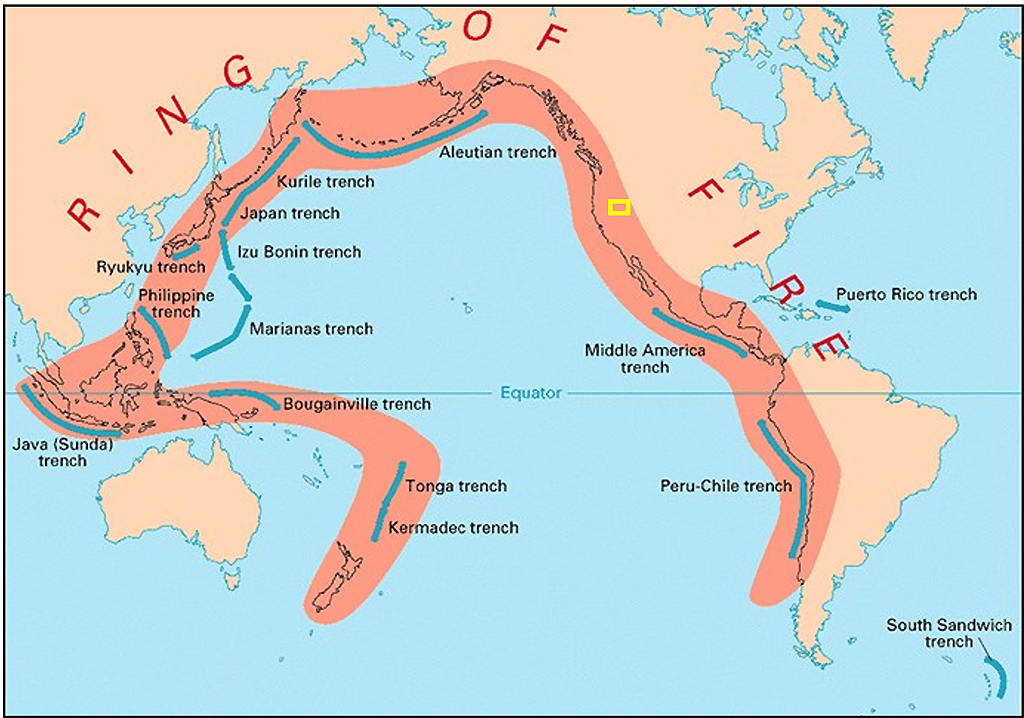

Approximate location of Lassen Volcanic National Park along the Circum-Pacific Belt / NPS graphic

Think of the volcanoes in Lassen as vertebrae in a backbone stretching 500 miles (804.7 km) north to south along the western edge of North America, from British Columbia down through Washington state, then Oregon, and on into California. This is the Cascade Volcanic Arc (aka Cascade Range), of which Lassen Peak is the southernmost active volcano. The Cascade Range is a part of the Circum-Pacific Belt (aka Pacific Ring of Fire) where 90 percent of earthquakes occur and the majority of the world’s volcanoes are located.

Plate tectonics play the starring role in the creation of the Cascade Volcanic Arc. Picture Earth’s outermost layer as a series of irregular slabs, or sheets, conveyed along by mobile, molten material beneath. This molten mantle material (the asthenosphere) is constantly in motion, ferrying the sheets all over the globe. Plate tectonics are always on the move, albeit slowly. Plate movement ranges from one centimeter to more than 15 centimeters (0.39 – 5.9 inches) annually, which sounds negligible until you start adding those centimeters/inches up over the course of millions of years.

The Cascade Volcanic Arc / NPS-Jason Kenworthy graphic

According to the 2014 Lassen Volcanic National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report:

The Cascade Volcanic Arc is a result of oblique [slanting] subduction [downward movement] of the Explorer, Juan de Fuca, and Gorda plates on the western edge of the continent … Landward from the plunging tectonic plates, magma has worked its way to the surface and built a series of conspicuous volcanic landscapes [including what is now Lassen Volcanic National Park].

Unlike the volcanoes of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park which are composed of more fluid, less silica-rich basalt lava, most (but not all) of Lassen’s volcanoes are comprised of igneous rocks andesite, dacite, and rhyolite, producing very viscous, silica-rich, highly-explosive lavas when erupting. As a result, the powerful eruptions of Lassen Peak between 1914 – 1917 projected huge amounts of ash and rock as high as 30,000 feet (9,144 meters) into the air, while sending lahars (ash and mud flows) moving as fast as 45-50 miles per hour (75-80 km per hour) downslope, carrying car-sized boulders miles away from the volcano.

Hot Rock, which was literally quite hot at the time of the photograph, is an example of a boulder carried downslope by a lahar during the 1915 eruption of Lassen Peak, Lassen Volcanic National Park / B.F. Loomis Historical Photograph Collection via NPS

Volcanoes

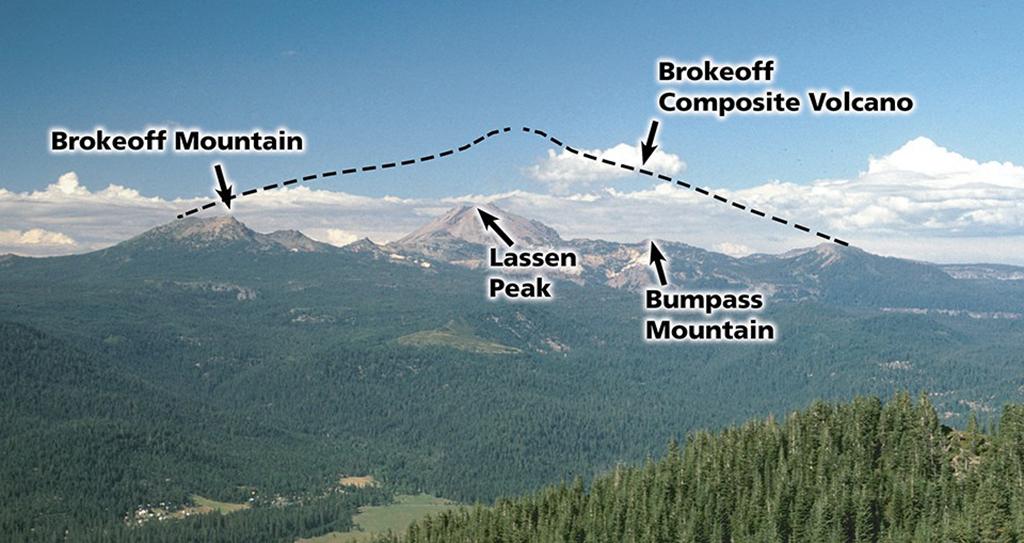

Lassen is home to all four types of volcanos found around the world: cinder cone (Cinder Cone), composite (Brokeoff Mountain), shield (Prospect Peak), and plug dome (Lassen Peak). These volcanoes collectively compose the Lassen Volcanic Center and are all related to a single, active magmatic system beneath the western portion of the park which began around 825,000 years ago and is still at work heating Lassen’s hydrothermal features (fumaroles, mud pots, hot springs) you see at locations such as Bumpass Hell, Sulphur Works, and Devils Kitchen.

What is the difference between the four types of volcanoes in Lassen, and how did they form?

According to park staff:

Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Cinder Cone Volcanoes - [These volcanoes] are built by gaseous lava particles violently ejected high into the air from a single vent, similar to a popcorn popper. The lava shatters into small fragments that solidify in the air and fall as cinders around the vent. As the cinders accumulate, they pile up to form a circular or oval shaped cone. Cinders, more properly known as scoria, are made of a low density basalt that has a bubbly or vesicular texture. As the lava cools quickly in the air, gases are trapped within the rock, creating this texture. Most cinder cone volcanoes have bowl shaped craters at the summit and lava flows are commonly emitted from their bases.

Brokeoff Mountain, a part of former composite volcano Mount Tehama, Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS photo

Composite Volcanoes -Sometimes called stratovolcanoes, these are generally steep-sided symmetrical cones of large dimensions formed from multiple eruptions that deposit layers of lava, ash, and cinder—comparable to a tiered cake. This is the most well-known type of volcano in the Cascade Range. Once standing over 11,000 ft (3,300 m) tall, Brokeoff Volcano— also known as Mount Tehama—has been eroded away by hydrothermal activity and glaciers over the past tens of thousands of years. Long ago, Brokeoff Mountain, Pilot Pinnacle, Mount Diller, and Mount Conard were all part of Mount Tehama. Today, these individual mountains are all that remain of the composite volcano.

Shield volcano Prospect Peak, Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS photo

Shield Volcanoes – [These volcanoes] are formed almost entirely of fluid lava that builds up gradually from thousands of lava flows—like layers of paint on a canvas. The buildup creates a broad, gentle sloping cone with a profile like a Viking shield—hence the name. The highly fluid lava flows, known as basalt lava, spread out over wide areas, then cool as thin, gently dipping sheets. The largest known volcanoes are shield volcanoes and include such famous examples as Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii and the largest mountain in the solar system—Olympus Mons on Mars.

Lassen Peak, a plug dome volcano, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Plug Dome Volcanoes – [These volcanoes, also known as lava domes] are formed by nonexplosive outpourings of viscous lava that piles up around a vent, but can be preceded or followed by explosive eruptions. Domes commonly occur within a crater or along the flanks of larger composite volcanoes. Growth occurs largely from within by expansion of lava that is too thick to flow. As it grows, the outer surface cools and hardens, then shatters, spilling lose fragments down its sides. At 10,457 ft (3187 m), Lassen Peak is one of the largest plug dome volcanoes on earth. A smaller dome formed inside Lassen’s crater. During its last eruption, a large explosion shattered the dome causing hot blocks of lava to fall from the peak, creating the Devastated Area.

Volcanic Landforms

In addition to Lassen’s volcanoes, you will see other volcanically-derived landforms in this national park.

Morning sunlight over Chaos Crags and Chaos Jumbles, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Chaos Crags and Chaos Jumbles – Chaos Crags are a series of lava dome volcanoes. Scientists believe repeated freeze/thaw widened cracks in the dacite rocks composing these volcanoes, weakening the rocks’ hold and causing them to break free to rush at speeds of nearly 100 mph (161 kph) down the steep slopes. Three different avalanches occurred, with rocks gaining such high speeds as to trap air beneath, between the ground and rocks, reducing friction and allowing the rocks to ultimately cover 2.5 square miles (6.8 square km). As the rocks came to a rest on the edges of the avalanche flow, rocks in the center continued to move at a rapid rate, creating “frozen waves” to make the undulating landscape you see today along the park road near Manzanita Lake.

Fantastic Lava Beds, Painted Dunes, and Snag Lake in the distance, as seen from the summit of Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Fantastic Lava Beds – Erupting from the base of Cinder Cone, these lava flows spread northeast and southwest, damming creeks and creating Snag Lake on the south and then Butte Lake to the north.

Painted Dunes – several units of the National Park System have painted something-or-others, be it a painted desert, painted hills, or, in the case of Lassen Volcanic National Park, painted dunes. These bright yellow, red, and orange dune mounds are the result of an ash deposit from Cinder Cone. Some areas around Cinder Cone are covered with ash as much as 8 feet (2 m) thick. The bright colors are the result of oxidation occurring when the ash landed on still-hot underlying lava flows.

The colorful Painted Dunes, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Hydrothermal Features – These areas of extremely hot water are indicators of the magmatic activity still churning beneath the park’s surface. There are eight hydrothermal areas within Lassen, the largest of which is Bumpass Hell, named after Kendall Vanhook Bumpass, an explorer and mountain man who fell into a boiling mud pot in 1865 and had to have his leg amputated. You can hike 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to this area and walk a series of boardwalks over fumaroles (steaming vents), hot springs, and mud pots (an acidic hot spring filled with mud).

A first view of Bumpass Hell along the trail, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Other hydrothermal areas are Sulphur Works, located alongside the park road 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the Khom Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center; Devils Kitchen and Boiling Springs Lake, both accessible via a hiking trail in Warner Valley; Terminal Geyser in the area near Drakesbad Guest Ranch; Cold Boiling Lake, reachable either via trail from Bumpass Hell or from the Kings Creek Picnic Area Trailhead; and Pilot Pinnacle, and Little Hot Springs Valley, both of which have no parking areas or trails for access.

Glaciers

While Lassen Volcanic National Park is all about the volcanic wonders to be found there, glaciers are worth a mention, too, since they figured heavily in sculpting the park’s features beginning around 27,000 years ago, when Lassen Peak was forming. Most of the glacial evidence seen today is erosional in nature, from bedrock removal, to creation or enlargement of lakes, to polished and grooved striations on bedrock (which can be seen right next to the Bumpass Hell parking area), to formation of U-shaped valleys, aretes, and cirques.

Classic glacial landforms you might see during a visit to Lassen Volcanic National Park / Trista Thornberry-Ehrlich graphic via NPS

Glacial deposition, as much as erosion, helped shape the Lassen landscape, including development of moraines (rocks and debris left behind by receding glaciers) and deposits of erratics (rocks moved by glaciers and deposited in new locations, sometimes miles from their original placement). The large boulder near the Bumpass Hell parking area is a textbook example of a glacial erratic.

Glacial erratics can get quite large, demonstrating the carrying power of those "rivers of ice," Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson