While Carlsbad Caverns National Park counts 119 different caves, currently only one is open to the public for tours: the famous Carlsbad Cavern. Slaughter Canyon Cave and Spider Cave, two other caves normally open for touring (guided only) are currently closed. World-renown Lechuguilla Cave is open only to researchers.

The trail through Carlsbad Cavern, Carlsbad Caverns National Park / Rebecca Latson

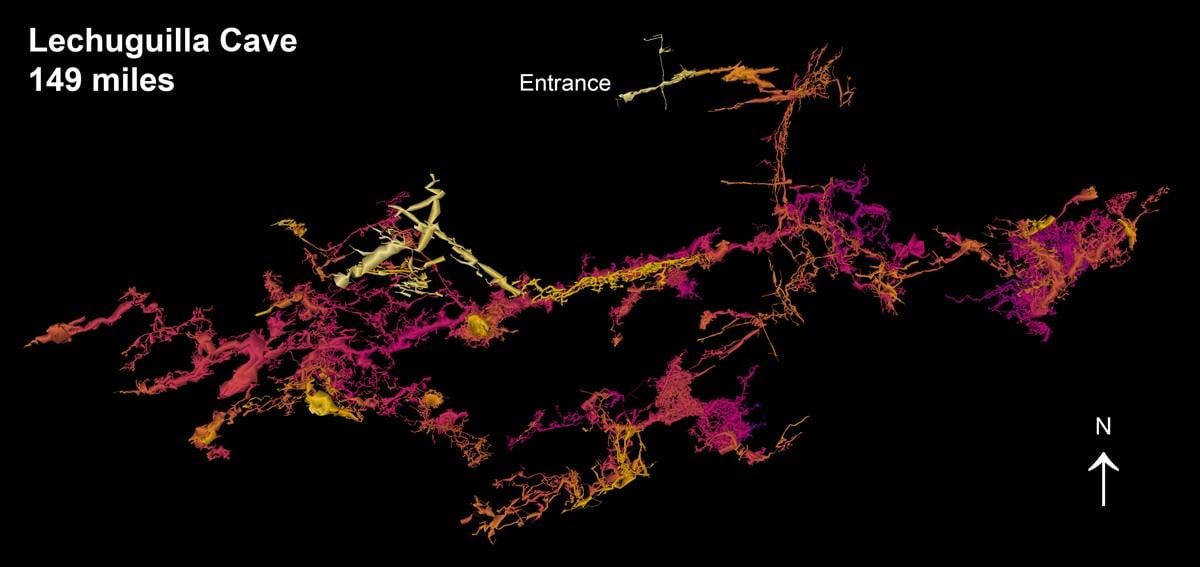

Two of the most well-known caves are Carlsbad Cavern and Lechuguilla Cave. More than 140 miles (225 kilometers) long, Lechugilla Cave is not open to the public due to its delicate formations; only permitted scientific expeditions are allowed. Cavern exploration continues, with cavers pushing new routes and discovering deeper depths to the caverns and more unique cave characteristics.

Initially, Lechuguilla Cave held no significance to the park, when spelunkers (cave explorers) in the 1950s discovered the cavern by hearing gusting wind issuing from the opening. It wasn't until three decades later, in 1984, that cavers from Colorado gained Park Service permission to enter the cave for further exploration. On May 26, 1986, cavers achieved a breakthrough by discovering a way into larger walking passages. As such, Carlsbad Caverns is now home to one of the longest caves in the world, and the second deepest limestone cave in the United States. The Big Room in Carlsbad Cavern, itself, is one of the largest by volume in North America.

Map of the more than 145 miles of passageways in Lechuguilla Cave as of July 2019/NPS

In addition to its record size, Lechuguilla Cave revealed a variety of rare speleothems (structures formed from cave deposits), some of which had never been seen elsewhere: gypsum chandeliers, gysum hairs and beards, and gypsum soda straws; hydromagnesite balloons, cave pearls, subaqueous helictites and rusticles, u-loops, j-loop and lemon yellow sulfur deposits.

While the Lechuguilla Cave is incredibly rich in speleothems compared to any other cave in the area, it does not contain a room larger than Carlsbad’s Big Room.

Temple of the Sun in the Big Room, Carlsbad Caverns National Park/NPS, Peter Jones

Other speleothems commonly found in the caverns include stalactites, draperies, ribbons or curtains found on ceilings, while on the cave floor are totem poles, flowstone, rimstone dams, lily pads, shelves, cave pools and stalagmites.

Scientists believe delving deeper within these caverns may ultimately reveal other rarities, such as chemolithoautotrophic (rock eating) bacteria, and perhaps even subterranean organisms bearing medicinal properties to benefit humans.

Scientists also understand the delicate cave ecosystems within this national park are always under threat of contamination from oil and gas exploration on nearby U.S. Bureau of Land Management lands.