From a failed health experiment, to slave mining of a valuable chemical compound, to potential ways to make money from Mammoth Cave’s notoriety, to forcible removal of people from their property, Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky is rich in history both above and below ground.

Tourists exploring one of the two TB huts circa 1912, Mammoth Cave National Park / NPS - Library of Congress Reproduction No. lc-usz62-64952

TB Huts And A Failed Experiment

Prior to the time when patients suffering from TB were urged by their physicians to travel someplace with drier air, one Dr. John Croghan, himself a TB (aka “white plague”) sufferer, hypothesized spending time in Mammoth Cave might be restorative to those with this bacterial infection. Evidence of minimal-to-no decay of timber and dead animals within the cave’s nether regions, as well as assumptions of the day regarding the curative powers of Mammoth Cave’s uniform temperature and humidity encouraged Croghan to conduct an experiment during the winter of 1842. Slaves constructed two stone cabins and eight smaller wooden structures within the cave in which would live 16 individuals suffering from TB. Initially, they all seemed to show improvement and Croghan happily began plans to build a hotel within Mammoth Cave. As the winter wore on, however, all 16 began suffered worsening symptoms.

According to park staff:

… As winter progressed, it became clear that the dank, dark conditions worsened the patients’ symptoms. Smoke and ash from lard oil lanterns and a large fire used to light the cave continuously filled the chambers while the dampness of the air further degraded damaged lungs. Cedar trees and bushes brought in to lighten the atmosphere quickly withered. While some cooking was completed within the cave, other meals were prepared off-site by enslaved individuals and brought into the cave. A server named Alfred noted, “I used to stand on that rock and blow the horn to call them to dinner. There were fifteen of them and they looked more like a company of skeletons than anything else.”

Tours of Mammoth Cave had begun in 1816. The tourist infrastructure developed over the next several decades, including the expansion and remodeling of the existing hotel and creation of new roads by Dr. Croghan. These improvements and public tours of the cave system continued during the medical experiment. Unsuspecting visitors would occasionally encounter ghastly patients in hospital gowns shuffling along passageways or hear hollow coughing echoing in the distance.

As the weeks wore on, five patients ultimately died inside the cave, their bodies laid out on what is now known as corpse rock. Dr. Croghan despondently returned to the surface with the remaining survivors. The experiment was not repeated and the wood frame huts were dismantled, while the two stone cottages remain along Broadway within the Mammoth Cave Historic District.

The experiment lasted no more than five months, from autumn 1842 to early 1843. While the cool cave setting conformed to the treatment standards of the times, the unventilated, damp environment made the disease worse. Like his patients, Dr. Croghan ultimately passed of tuberculosis in 1849.

Take the park’s Extended Historic Tour and you’ll see for yourself the remaining stone TB huts.

Saltpetre

Wars make things expensive – especially imports. The War of 1812 (which lasted three years) between the United States and Great Britain, made gunpowder importation – in high demand at the time - quite expensive due to the British blockade of eastern seaports. Mammoth Cave helped solve that problem just a little, thanks to bat poop.

Bat guano (poop) deposited over thousands of years into the cave soils generated dirt rich in calcium nitrate. This mineral, when mixed with high-potassium minerals, created saltpetre, a primary component of black gunpowder.

Not many people voluntarily wanted to perform the labor-intensive work necessary for mining saltpetre, so enslaved African-American men were leased from other states and brought in to shovel, haul, and sift the cave dirt. The hours were long and the conditions poor.

According to park staff:

The mining process involved extracting the calcium nitrate using water and large square vats to filter the cave dirt. A solution of water and calcium nitrate would then be pumped to the surface where it was combined with materials such as wood ash, and sometimes even ox blood, to create the saltpetre.

These enslaved miners built many of the first trails inside Mammoth Cave. They hauled rocks away from the center of the passageways and laid down flat rocks in order to make it easier for their carts, pulled by oxen and donkeys, to traverse the passages and gather more dirt for the mining operation.

The war eventually ended and the demand for saltpetre declined. The mining operation eventually stopped, and the then-cave owners simply left everything there. The atmospheric conditions of the cave have preserved these now-200-year-old artifacts for present-day cave visitors to view.

The Cave Wars

After the War of 1812 ended and saltpetre mining “petered out,” the public wanted to see more of Mammoth Cave. Rival cave owners knew a good thing when they saw it.

The potential for commercial success at Mammoth Cave increased as guides continued exploring new passageways extending further away from the privately-owned Mammoth Cave area. Rival cave owners realized their small caves – while perhaps just as decorated with amazing formations (speleothems) – were no match for this much larger, more well-known cave venue. So, they worked on two things to increase their chances at capturing a greater share of visitation. Landowners positioned themselves or their representatives along the road to Mammoth Cave to redirect some of the traffic toward their own caves, and at the same time hunted for a “back door” into those Mammoth Cave passages that were lengthening great distances beyond the original opening.

According to park staff:

In the early twentieth century, an era of competition gripped the Mammoth Cave region. Rival cave owners battled in the courtroom, as well as along the roads, for the tourist dollars passing through Kentucky’s cave country en route to the future national park. Road signs and solicitors lined the highways to redirect travelers to one of many competing show caves. More than twenty caves were open to the public in the Mammoth Cave region by the 1920s, when the feuding reached its climax. Yet, the Kentucky Cave Wars had its roots in the nineteenth century, when cave developers and promoters first began siphoning tourists away from the world-famous Mammoth Cave.

George Morrison

The Kentucky Cave Wars earned their name and reputation when the competition reached a feverish pitch in 1915, upon the arrival of George Morrison to Mammoth Cave. While other cave developers, such as Larkin Procter, Lyman Hazen, and even railroad agents for the L&N Railroad, had found success in commercializing caves in the vicinity of Mammoth Cave, they’d all failed in their attempts to find a connection to the world-famous cave. Within six years of his arrival to the area, George Morrison had illegally gained access to Mammoth Cave, determined where the most remote passages lied in relation to the surface, obtained the rights to property along the Cave City Road, and blasted open a backdoor that he named the “New Entrance to Mammoth Cave.” Seemingly overnight, Morrison became the most successful cave developer in the region and continued to grow his cave empire with the addition of a hotel and more entrances to his beautiful section of Mammoth Cave.

Luring Travelers In

As the war erupted in the courtroom over Morrison’s use of the name, “Mammoth Cave,” the fighting also moved to the roadsides. The Mammoth Cave Estate, the New Entrance, and others relied more and more on reaching visitors as they drove to the cave region and depended on increased signage to get their attention. When that proved to be insufficient, solicitors (called “cave cappers” because of the hats they commonly wore) were hired to line the highways, draw motorists to their booths, and give “official cave information” intended to lure travelers to their cave of employment.

Positioning along the road was critical. If a cave business couldn’t employee cappers to draw tourists to their location, then a cave had to be conveniently located along the road. Unfortunately for the Collins family, owners of Great Crystal Cave, their business had neither advantage.Tragedy in Cave Country

On January 30, 1925, Floyd Collins attempted to remedy his family’s situation by exploring Sand Cave, just off the Cave City Road, for potential development. Floyd’s journey into Sand Cave proved tragic, as his foot became pinned between a rock as he was exiting the cave. Floyd Collin’s entrapment, and subsequent death, became a national news phenomenon and drew thousands of spectators to the area. The failed rescue effort shed a light on the competition in the Mammoth Cave region and helped accelerate an already-growing movement to turn the area into a national park.

Eminent Domain And The CCC

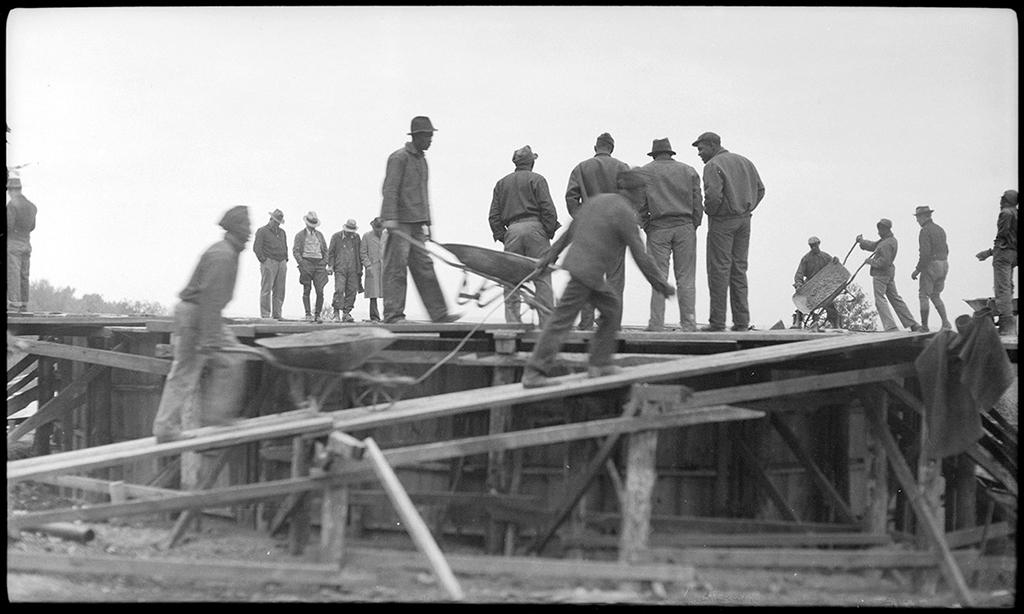

CCC enrollees hauling concrete up a board ramp during the construction of one of four 50,000-gallon concrete reservoirs planned for the park's new water systems, ca 1930s, Mammoth Cave National Park / NPS file

Mammoth Cave National Park was authorized by Congress in 1926 and eventually established in 1941. Prior to establishment, the people who lived within the park’s proposed boundaries either had their farmsteads purchased with donated funds, or they were forcibly removed and their land was acquired by right of eminent domain. These proceedings were often bitter and contentious, and many landowners claimed they were not paid fair market value. The forcible removal means leaving behind homes, farms, other buildings, and even churches and cemeteries where rested friends and relatives.

Once the landowners were gone, the area around Mammoth Cave needed to be prepared for the future park. With that in mind, from 1933 to 1942, the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) set up four camps and razed buildings and cleared the area to “naturalize” the landscape, and built roads, trails (both above ground and inside Mammoth Cave), and facilities, planted trees, and even made renovations to the existing Mammoth Cave Hotel.

According to park staff:

Evidence of the CCC can still be seen throughout Mammoth Cave National Park. Many structures that were built by the CCC are still standing today. These include recently remodeled employee housing and other buildings in the park’s administration area. The famous CCC stonework can be seen on the Three Springs pump house and chlorination house, around the park’s amphitheater, and along the banks of the Green River Ferry crossing where rocks were stacked to keep the banks from eroding.

Many of the trees that are seen today are from the CCC era. With much of the area being barren of trees when the park was created, the CCC took over 9,000 man hours to plant more than 1 million trees in what is now Mammoth Cave National Park.

The largest transformation that occurred was inside the cave itself. Many of the cave’s trails were single-file and made up of flat rocks stacked end to end. The CCC worked to improve and create what would be 24 miles of trail through the cave passageways. Another structure that you can still see today that the CCC constructed is the Frozen Niagara entrance and the rock landscaping around it.