You might think Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota is just like Jewel Cave National Monument, also in South Dakota. Both are located within the Black Hills, which is in turn a part of the Great Plains Physiographic Province. Both caves were formed from the dissolution of limestone, meaning they are considered “karst” caves - a landscape where bedrock has been dissolved by water. Both caves are in the same geologic unit – the Pahasapa limestone. Both are close to each other geographically (although not connected and not currently believed to be connected). But, Wind Cave does have a few differences.

Simplified geologic map of Wind Cave National Park, marked with the location of Wind Cave passages / NPS

Wind cave is the third longest cave in the United States, with an approximate length of 167 miles (268.76 km), and the fourth longest cave in the world. This current discovered length is a “fraction of the volume yet to be found,” according to the 2009 Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report, which goes on to say:

Wind Cave is a barometric breathing cave. Changes in barometric pressure as a result of fluctuations between day and night and changes in weather cause air to rush into or out of the cave, equalizing the pressure between the inside and outside. When the barometer rises, air rushes into the cave; when the barometer drops, air rushes out. [Research] demonstrated that wind blows primarily inward during the winter and outward during the summer, [and] the average outward-flow velocity is almost always higher than the inward-flow velocity year-round.

Wind Cave is one of the oldest caves in the world. The cave developed along gypsum deposits and paleokarst zones [ancient karst features that have been fossilized or preserved] and intersects one of the world’s best examples of paleofill—ancient sediment that filled caves and sinkholes that existed before Wind Cave formed … Major cave expansion occurred during Paleocene–Eocene time (60–40 million years ago).

So, how did it all begin? Let’s start at the top and work our way down.

The rolling Black Hills in which Wind Cave sits are the result of crustal uplift. If you were to fly over the exposed rocks of the entirety of the Black Hills, you would notice a “bullseye” pattern around the center of the hills, with granites (igneous rocks) and gneisses (metamorphic rocks) forming the core. Moving outward from that core, you would to see younger sedimentary rocks (limestones, shales, sandstones).

According to park staff:

The oldest rocks in the park are schists and pegmatites. Schists are metamorphic rocks which formed under heat and intense pressure during an early episode of mountain building, about 2 billion years ago. They have almost parallel bands, or foliation, caused by the growth of mica crystals under pressure.

Pegmatites are made of large crystals of glassy-gray quartz, pink feldspar, silvery micas, and shiny black tourmaline. Pegmatite is an igneous rock, similar to granite. It hardened from magma and hot fluids. In places, the pegmatite intruded into the schists. This proves the pegmatite is younger than the schists, but still very old at 1.7 billion years. The emplacement of the pegmatite probably occurred during another mountain building event.

An outcrop of pegmatite at the Exposing The Past exhibit along the park road, Wind Cave National Park / Rebecca Latson

A close-up view of pegmatite, displaying quartz, pink feldspar, platy mica, and black tourmaline, Wind Cave National Park / Rebecca Latson

One mile (1.61 km) north of the Beaver Creek Bridge along the park road is a paved parking area on the right side of the road, leading to an exhibit titled Exposing the Past. Here, you can see fine examples of granite pegmatite, exposed due to erosion of the overlying rock. Had there been no erosion, the Black Hills would be 7,500 feet higher (2,286 m). According to the exhibit sign, “The Black Hills formed about 65 million years ago in the most recent of at least three mountain building episodes in this region.”

Aerial view of the location of the Exposing the Past exhibit, Wind Cave National Park / Google Maps

These pegmatites, along with limestones and sandstones – rocks more resistant to erosion – form the ridges you see in the park, while the more easily-eroded rocks like schists and shales, form the valleys.

The Cave

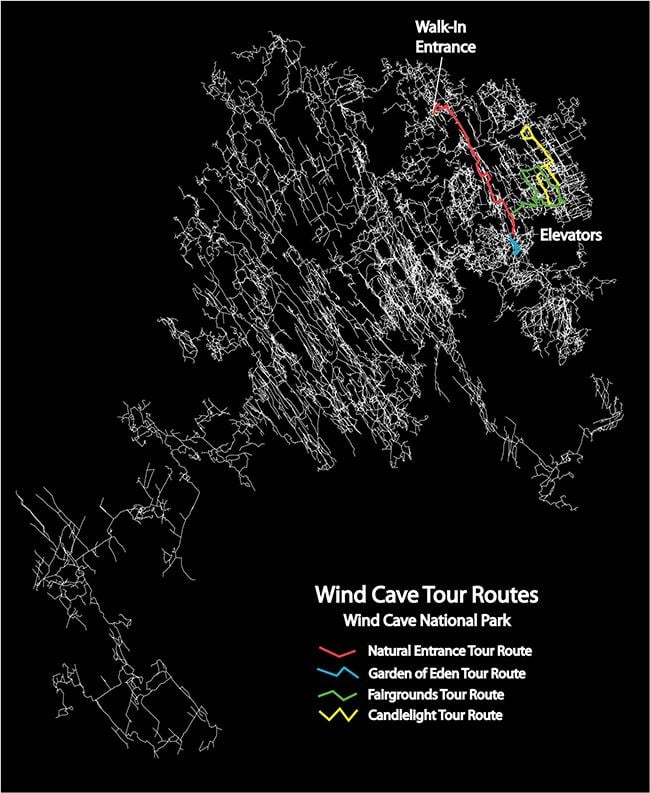

The extent of Wind Cave's passages with tour routes outlined in color, Wind Cave National Park / NPmaps.com

Some 360 – 340 million years ago, a shallow sea covered the area now within Wind Cave National Park’s boundaries. This shallow sea was subject to high rates of evaporation, leaving behind “lenses of chert, gypsum, and anhydrite,” according to the NPS. Gypsum and anhydrite are evaporites. During that time, the Pahasapa limestone was deposited into the shallow sea. The evaporites ultimately dissolved to create voids into which the overlying Pahasapa limestone collapsed. Thus began the main phase of cave formation, which occurred 60–40 million years ago.

Eventually, sea level dropped, exposing the limestone to naturally acidic freshwater. Sinkholes, fissures, and some caves began forming. Seas advanced again, depositing red clay, sandstone, and limestone, collectively known as the Minnelusa Formation. You can see deposits of these reddish “paleofills” (ancient sediments) in the upper regions of the Fairgrounds and Garden of Eden rooms.

The seas advanced and retreated for the next 240 million years, with deposition and erosion/evaporation continuing apace. As the Black Hills uplifted, fractures in the rock opened within the developing Wind Cave.

Caves form slowly. In the case of Wind Cave, no running water like a river or stream created and enlarged the cave. Instead, the water there remained in place for a long time, slowly enlarging the cracks into rooms and the maze-like passages we see during a guided tour.

It’s easy to imagine everywhere we step aboveground within the park, we are walking atop Wind Cave’s subterranean passages, but that is not so. This cave and its three different levels of passageways resides within an area of 1.25 square miles (3.24 square kilometers), most of it beneath the land on which sits the visitor center and nearby administrative/ranger housing buildings. Think of the cave as a bowl of spaghetti, the noodles (passageways) crammed in and looping over and under each other, restricted by the bowl’s sides, from rim top to bowl bottom. Similar to that spaghetti bowl, Wind Cave is extensive, but more vertically than horizontally.

Wind Cave Speleothems

Tour Wind Cave and you will be privy to some amazing cave formations (speleothems) with descriptive names such as frostwork, helictite bushes, gypsum flowers, popcorn, drapery and flowstone, all formed by water and the minerals calcite and gypsum. Wind Cave holds the world’s largest concentration of boxwork, a rare, honeycomb-like structure made of calcite “blades” covering the cave's walls and ceilings.

Boxwork on Wind Cave's ceiling along the Natural Entrance Tour, Wind Cave National Park / Rebecca Latson

To see photos and read about the different speleothems found within Wind Cave’s depths and how they formed, click here.

Fossils

There are fossils in Wind Cave spanning 350 million years. The Pahasapa limestone bears testament to ancient marine life. Look closely at the walls and formations and you will see brachiopods and rugose coral along several of the tour routes.

Fossil brachiopods found in Wind Cave at Wind Cave National Park / NPS - Theodore Herring

While Wind Cave is the only cave open to the public, it is not the only cave within this national park, nor is it the only cave with fossils. In 2004, a physical scientist at the park discovered what is now called Persistence Cave. In 2013, this cave was tested as a paleontological site, and since then, bones of 22 species dating back over 11,000 years have been discovered.