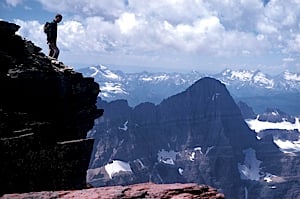

Glacier, like so many of the Western parks, is an open-air showcase of geology. Scan the horizon and you can see the effects of long-ago glaciers, glaciers still at work, and landscapes in various stages of healing in the wake of the scraping and freeze-thaw cycling of glaciers.

Lunch Creek, along Going-to-the-Sun Road, is a great place to see an example of a glacial landform known as a cirque, Glacier National Park / Rebecca Latson

Glaciers once covered all but the highest peaks in the park. About 12,000 years ago, however, the last of the great valley glaciers melted. Today, Glacier National Park has only 25 glaciers, all of small size, nestled into the highest and coldest places along the continental divide.

Warmer temperatures have melted the park’s glaciers at a rapid rate. In fact, less than one-third of the glaciers present in the park in 1850 (during the Little Ice Age) still exist today. If temperatures continue to increase as expected, it is likely that the park’s glaciers will be gone by 2030 at the latest, and perhaps as early as 2020. Indeed, in April 2010 the U.S. Geological Survey ruled that of the 37 named glaciers in the park, only 25 remained large enough to still be considered glaciers. Of the 12 that have melted away, 11 have done so since 1966, according to the USGS.

A great place to see the impacts of glaciers and the uplifting of the continent is at Logan Pass. There, at the the apex of the Sun Road, the pass is pinched tightly between Clements Mountain and the southern tip of the Garden Wall, a massive rib of rock that carries the Continental Divide through the park’s interior. From this saddle the pass sends Reynolds Creek and Logan Creek in opposite directions as their waters cascade down massive U-shaped valleys scooped out during the park’s glaciated past.

Glacier is an open air geology classroom.

NPS photo

Farther north are the bulk of the park’s glaciers — thick sheets of ice named “Ipasha,” “Old Sun,” “Grinnell,” “Swiftcurrent,” “Thunderbird” and “Rainbow” — while to the south stands a maze of mountains, valleys, meadows and backcountry lakes that it would take a lifetime to know.

Repeated episodes of glaciation have left Glacier with an abundance of distinctive glacial landforms.

There are "cirques," the bowl-shaped depressions on mountainsides that were once occupied by glaciers that formed from snowfields. And 'arêtes," the narrow, jagged ridges that separate the glaciated valleys. An arête has very steep sides and the top of the saw tooth ridge may be too narrow to safely walk on. The Garden Wall is a perfect example of an arête.

Then, too, there are "cols," which are gaps or saddle-shaped depressions in a ridge or between two peaks. These gaps form passes and give an arête its sawtoothed appearance.

A "horn," meanwhile, is a spike-shaped mountain whose conspicuous pointed shape results from glacial erosion on all sides.

Lake McDonald lies in a glacial trough with a classic U-shaped profile. Tributary valleys “beheaded” by a glacier in the main valley end abruptly at points high on the walls of the glacial trough. Waterfalls result when streams spew meltwater from these hanging valleys. One well-known waterfall created by such geologic machinations is Bird Woman Falls, which you can spot while driving up towards Logan Pass from West Glacier.

Ridges consisting of unsorted silt, sand, gravel, and boulders are called moraines. The maximum advance of the glaciers during the Little Ice Age is marked by terminal moraines (also called end moraines). The park also has some lateral moraines and medial moraines.

Eskers, sinuous ridges composed of stratified sand and gravel, were once streambeds inside or atop valley glaciers.

Lakes occupying water filled cirques are called "tarns." A “string” of tarns linked by a stream in a descending series along a glacial trough is suggestive of rosary beads. This inspired the name “paternoster,” which derives from the Latin for "Our Father," the first words of the Lord's Prayer. Visitors on Going-to-the-Sun Road get a good look at a paternoster lakes system in the upper reaches of the glacial trough in which Lake McDonald lies. Long, narrow lakes – appropriately named finger lakes – have been impounded by natural dams in some glaciated valleys. There are several finger lakes (including Bowman Lake) on the western flanks of the park.