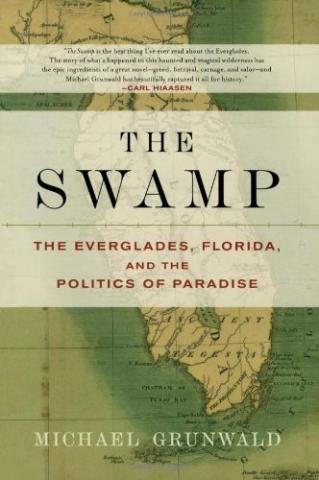

A fan of non-fiction books, particularly those with a natural history bent, I figured The Swamp by Michael Grunwald would be a perfect match for my interests. After all, as the subtitle pointed out, this book focuses on "The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise."

I thought that within the covers of The Swamp's 370 pages (not counting additional pages of notes, acknowledgments, and index), I'd come away with a deeper understanding of how Everglades National Park came to be.

Oh, I realized going into the text that the book was more than just a history of the park. But while many others have found The Swamp fascinating, I found the going ponderous and at times numbing.

There's no doubt that Grunwald is a fine researcher and solid writer. Indeed, he's done an incredible job of piecing together the political history that surrounds the Everglades and the many attempts to dry it out. But perhaps his undoing was in trying to be so meticulous in his research that he ran out of room in his book.

After relatively quickly dispatching with the military efforts to run the Seminole tribes out of Florida, Grunwald turns his sights on the many characters who thought they knew the key to draining the Everglades and turning the vast river of grass into productive agricultural, and later residential, lands.

So many surface that the author seemingly doesn't have enough space in his 370 pages to truly bring them to life. Indeed, he seems to have encountered the same problem when describing the Everglades' flora and fauna and so, in one spot, resorts to a list:

"The Everglades was the only place on earth where alligators (broad snout, fresh water, darker skin) and crocodiles (pointy snout, salt water, toothy grin) lived side by side. It was the only home of the Everglades mink, Okeechobee gourd, and Big Cypress fox squirrel. It had carnivorous plants, amphibious birds, oysters that grew on trees, cacti that grew in water, lizards that changed colors, and fish that changed genders. It had 1,100 species of trees and plants, 350 birds, and 52 varieties of porcelain-smooth, candy-striped tree snails. It had bottlenose dolphins, marsh rabbits, ghost orchids, moray eels, bald eagles, and countless other species that didn't seem to belong on the same continent, much less in the same ecosystem."

Now, the entire book isn't like that. There are places where Grunwald elaborates, albeit briefly -- "Take the golden-brown Everglades goop known as periphyton. It was easy to overlook, clumped around aquatic plants like slimy oatmeal sweaters, floating in sloughs like discolored papier-mache, crumbling into a snowy powder during droughts. But it was the dominant life-form in much of the Everglades, measured by biomass. It was also the base of the Everglades food chain, providing grazing pastures for small fish, prawns, insects, and snails, which became prey for larger fish and birds. Today, microscopes reveal periphyton mats as action-packed worlds unto themselves, teeming with bacteria, diatoms, and single-cell organisms shaped like candles, spaghetti, bricks, nets, tissues and tunnels -- swimming, splitting, and swallowing one another whole."

These snippets are too short, in my opinion. Indeed, he speeds, admittedly, through "The First 300 Million Years (Abridged)" of the landscape's evolution, discarding in two pages what the late James Michener might have embraced for two or more chapters.

The Swamp is a good chronology of the politics that surround the Everglades. But to me it lacks the depth and drama that this geologic and human stew surely can provide.

Comments