Can something as seemingly inconsequential as a stone trigger a national park memory in your mind? If you pick up a rock on your next hike in a park, will you wonder about its origin?

Hiking down a trail too often is done with the intent to go from Point A (the parking lot) to Point B (a campsite, or scenic payoff) as quickly as possible. How many of us focus on where our feet land and not on what's alongside the trail, in the forest or desert, the nearby river or lake, or the mountains stretching ever upward overhead? In our technologically overloaded world it seems we've forgotten how to linger over something as simple as a pine cone, a marmot's burrow, a patch of purple and yellow asters, a splash of glacial scour, or even a rock.

It was something as simple as a rock that fit into Paul Schullery's hand that made him pause and look up as he hiked somewhere in the vast expanse of Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. Small and inconsequential on one hand, the fragment of something much larger and grander made him wonder about its source.

I have a habit in Waterton-Glacier that I have nowhere else. I pick up little rocks, study them for a minute, then look up to the mountains to find the parent of whatever little piece I hold in my hand. This leads me to consider all manner of connections and processes.

If I happen to be high on a dry slope at the time, the rock will be sharp and jagged -- a freshly fallen, randomly faceted, coarse-surfaced little thing whose shape my mental processes of organization involuntarily attempt to recognize -- an arrowhead, a cashew, a guitar pick, a badge. If it's flat (and most are flatter along one plane or another) I reflexively fit it into the curve between my thumb and forefinger, testing its heft and promise as a skipping stone, though I may be miles from open water.

If I happen to be loafing on the shore of a lake -- let's say one of the long, deep ones that radiate out from the central mountain spines of the park -- I find a whole different class of rocks. They have the same general assortment of shapes, usually flattened rather than round, and they come in the same colors, made much brighter by being wet. But their contours are softer. There are no sharp angles and edges, no fresh fractures, no raspy friction against the thumb. Again I look up to the mountains, to see if I can figure out where each piece started.

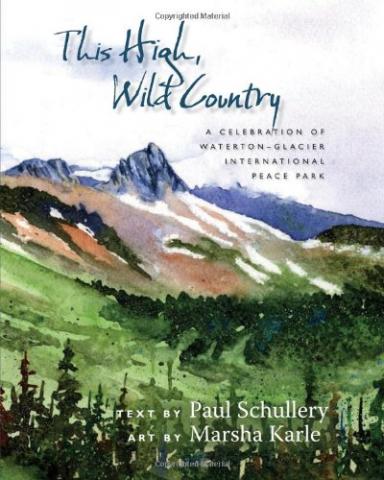

Mr. Schullery, long on the staff of Yellowstone National Park and now a scholar in residence at Montana State University and whose award-winning writings on nature and history have received acclaim, transforms an already rewarding experience of simply taking a walk in the park into one so much richer just by pausing to contemplate things as ordinary as rocks. In This High, Wild Country, A Celebration of Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park the author and his wife, Marsha Karle, who lends to the richness of this book with her watercolors, rambles on for a full 20 pages about the geology he finds under his feet, and high over his head, in the peace park.

And why shouldn't he? After all, Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta and our own Glacier National Park are geologic wonders, worked and reworked by upheavals and erosion, cleaving ice, dissolving waters, and even the burrowing of hoary marmots and the sharp, clattering hooves of bighorn sheep.

He does so not with a geologist's eye, but rather that of a national park visitor with a curious mind.

"I don't blame the geologists for my bewilderment about geology, any more than I blame General Motors that I don't really understand automatic transmissions," he tells us. "And historically, my geological bewilderment put me in very good company here in Glacier. For more than a century now, distinguished explorers and geologists have been poking around here, gradually answering the really important questions, then reconsidering them, then answering them again."

This High, Wild Country is not solely a celebration of geology, though Mr. Schullery certainly easily could have wandered much further on that subject, as the parks overflow with geology. Through its 117 pages of text Mr. Schullery and Ms. Karle, herself a long-time Park Service employee before letting her evolution into a successful artist come to full blossom, explores the parks' wildlife, the time-honored tradition of wetting a fly in its streams not so much as to actually catch anything but simply to enjoy the time spent waiting for a strike, camping, and, quite naturally, the glorious landscape.

He does so in a comfortable fashion, one that's both stream-of-consciousness and conversational, such as this passage on fishing some backcountry lake:

For a while I thought that my only consolation would be the glorious view. Steep ridges with dark, twisted strata ran up in various directions, towering more than two thousand feet above the lake on three sides, and were reflected hugely in the still water. But then, as so often happens when I start fishing lazily and without thought, I became engaged in the game. Up to my waist and shivering in the cold lake, I used what was left of the light to improve my gear, experimenting with smaller and smaller flies, tiptoeing into deeper spots to make longer and more delicate casts over the elusive little risers.

Complementing Mr. Schullery's words are his wife's watercolors and sketches, vibrant images that lend depth to the narrative. Some are as simple as a clutch of geraniums in purplish bloom and rounded cobbles on the bottom of a stream. Others depict the bears, wolves, and thrushes that call these parks home. And some capture the golden glory of autumn in the northern Rockies and the geologic imprint of the gorge sculpted by Avalanche Creek.

While This High, Wild Country is a great book to set back in an armchair before the fire and imagine a trip to Waterton-Glacier, it also should convince you to pause, if only for a minute, on your next hike to wonder about that stone at your feet.