Among the wildlife that roam the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, there are clear-cut headliners. The restoration of wolves, the endangered status of grizzlies, and the culling of bison never fail to grasp the attention of readers worldwide. Yet so many more species share this vast landscape, and despite calling it home for 7,000 years, where and how they’ve survived has been uncovered only in the past two decades.

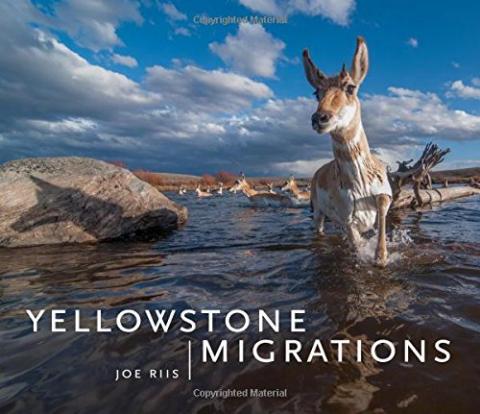

Photographer Joe Riis has worked for years with scientists to shed light on some of these less-famous animals. In Yellowstone Migrations, he focuses on the annual migration routes of three ungulates – elk, mule deer, and pronghorn – that are foundational to the ecosystem, both within protected areas and through a patchwork of subdivisions, ranches, and natural gas fields. He attempts “to get a sense of the mind and life of an animal … nothing else is as important to me.”

Yes, there are images of large herds sprawled across a beautiful plateau with a mountain backdrop. But the spirit of these animals shines more brightly in close-up shots, often captured with motion-activated cameras. In one image, a pronghorn almost jumps off the page, the buck at its zenith when leaping over a snowmelt-fed creek. In another, a pronghorn stares solemnly forward, one of its hind legs ensnared by a line of barbed wire. With snow blanketing the ground, its future seems dire. These mammals face challenges both natural (a herd of elk climbing a rocky mountain pass) and manmade (a mule deer darting across a road).

A handful of essays complement the photographs in Yellowstone Migrations, just as Riis’ images have breathed life and color into scientific research. These elk, deer, and pronghorn have been so core to the region that humans didn’t study their movement patterns until the past 20 years. What they found were treks that could reach 150 miles both ways, making them among the longest migrations on the continent.

This hardcover book shows how art and science together can make a difference in awareness, understanding, and policy, and underscores how these humble ungulates are “the lifeblood of the landscape” in middle America.

Add comment