Imagine taking the time to go into your backyard, or the nearby woods, or even a pond close to your home, to catalog all the life you found in it. Not just the deer or snakes or fish, but the birds and insects, reptiles, plants and fungi and everything else biological or botanic. Imagine how fascinating that would be.

At Great Smoky Mountains National Park they've been working on just that, and what they've found has been incredible. Since the park embarked on its All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory, or ATBI, researchers have discovered 858 species new to science, and 5,116 species previously unknown to Great Smoky Mountains.

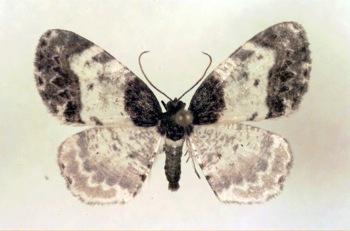

"New species to science (ie., those that have not been seen before and don't have a name) have been found in nearly every major taxonomic group, except plants and vertebrates," says Becky Nichols, the park's entomologist. "Many examples can be found among the insects, but also in mites, spiders, soil invertebrates, algae, tardigrades (water bears), slime molds, lichens, bacteria, etc."

True, these finds do not fall under the "charismatic mega-fauna" category, such as grizzly bears or wolves, but it's amazing just the same that so many previously unknown species are coming to light thanks to the park's investment in this inventory. Just as intriguing, if not more so, is that some of the species weren't thought to inhabit North America.

"A surprising finding is that some of these new to science species belong in genera that have not been recorded on this continent before," says Ms. Nichols. "Many of the new distributional records (ie, those species that do have a name, but have not been found in this location before) exhibit the same pattern, with surprising new range expansions. Others are very common and have been expected to be here, but simply have not been documented before because no one has really looked. New distributional records have been found among plants and vertebrates, also."

Great Smoky Mountains is not the only park reporting discoveries of new species. Back in January 2006 news broke that 27 new bug species had been found in new caves found in Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. Taxa inventories also have been ongoing at Point Reyes National Seashore and at Big Thicket National Preserve. A proposed Centennial Initiative project calls for nearly $3.3 million to be spent at Big Thicket on expansion of its ATBI project to perform a complete inventory in 10 other national parks, and eventually to 72, over the course of a decade.

In Washington, John Dennis, the Park Service's deputy chief scientist, says such work goes right to the agency's basic mission.

"The scientific exploration that is characteristic of the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory develops important, base information for improved scientific understanding and park management," he says. "As inventories are undertaken in more and more parks throughout the national park system, they will, over time, provide comprehensive inventories of all life-forms.

"Knowledge from these inventories, integrated with results from other scientific studies, will help park managers understand better how species interrelate and function in self-sustaining ecosystems," adds Mr. Dennis. "Because of their relatively undisturbed ecosystems, national parks are particularly well-suited to the scientific of biodiversity. This exploration, vital to park preservation today, will become even more important in the future."

In truth, the national park landscape is largely unexplored territory. Great Smoky Mountains, which covers roughly 500,000 million acres, is thought to contain "one of the richest and most diverse collections of plants and animals in the temperate world." And yet, it's estimated that while more than 100,000 species inhabit the park, just a tiny fraction have been identified.

"This richness has led to the park's designation as an International Biosphere Reserve," according to Discover Life, a non-profit organization whose mission is to share knowledge of nature with hopes of improving education, health, economic development, agriculture and conservation throughout the world.

"Climate, topography, the north-south orientation of the mountains, large tracts of old-growth and contiguous forests, and protection as a national park have all contributed to this abundance," the group says in its overview of the ATBI at Great Smoky Mountains.

At Great Smoky, officials are working with Discover Life in America, a non-profit group that is overseeing the entire ATBI in the park.

Ms. Nichols says that as more and more pressures, ranging from human visitation and poor air quality to climate change, are exerted on Great Smoky Mountains, it becomes even more important to complete the inventory.

"With regard to threats to our resources, knowing what is here is imperative to being able to respond to the threats appropriately," she says. "We would not know if something is being affected by any of these threats if we didn't even know they existed here. Even in our day-to-day activities, we frequently use species inventory information. Examples might include adding more pullouts to a road, or adding a couple campsites to a campground, or even dealing with a proposed road through the park.

"We evaluate all options by looking at the natural resources in the area, among many other things. Additionally, species inventory information often leads to improved monitoring capabilities for examining long-term trends in plant or animal populations."

With four more years remaining on Great Smoky Mountains' inventory, which got under way in 1998, expect more species to be uncovered.

You can learn more about ATBI work in the parks at this site, this site, and this site,

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

The outcome of this endeavor shouldn't be all that surprising. Microbiologists estimate that a mere 2% of all existing microbic life forms have been catagorized to date, again a function of research dollars (and time) not being allocated to the expansion of these types of projects. Early on in life, I was told, 'It's amazing what you can discover in life and all that you will see that have yet to be noted if you just make the effort to LOOK!". Kudos to the project leaders in the Great Smoky program for following the next step in the logical progression of biologic investigation.