Colorado's Mount of the Holy Cross used to be a National Monument administered as a unit of the National Park System. Sixty years ago, however, Congress abolished the national park and revoked the site's National Monument designation. Holy Cross National Monument had been a national park for just 17 years.

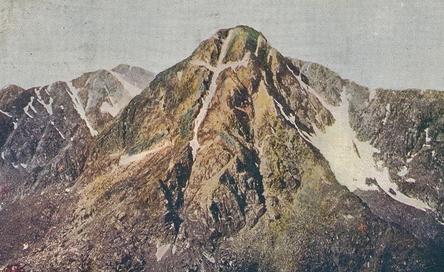

Mount of the Holy Cross is located near Vail in the Sawatch Range of the Rockies about 100 miles west of Denver. It is a distinctive-looking Colorado "fourteener" (elev. 14,005 ft.). High on its northeast face is a large cross-shaped feature formed by a 1,500 foot-high couloir (deep gully) that is horizontally intersected by a 750-foot long bench.

Since both the couloir and the bench hold snow much better than the surrounding rock, a distinct white cross takes shape in the warmer months. Though the big white cross can be discerned from more distant vantage points, it is by far most clearly seen from the summit of nearby Notch Mountain (elev. 13,237), which lies to the east. (People atop the Vail Mountain Ski Area can see the mountain looming to the south, but they can't see the face that has the cross.)

Into the Public Eye

During the pioneer era, the mountain's remoteness kept it hidden from view and shrouded in mystery. Few whites visited the rugged northern Sawatch Range, and the mountain with the great white cross remained the stuff of rumor until after the Civil War. The mountain wasn't considered "discovered" until the late 1860s when writer Samual Bowles reported seeing it from Grays Peak at a distance of about 40 miles. In The Switzerland of America, Bowles' 1869 book about the Mountain of the Holy Cross, he wrote: "... the snow fields lay in the form of an immense cross, and by this it is known in all the mountain views of the territory. It is as if God has set His sign, His seal, His promise there--a beacon upon the very center and height of the Continent to all its people and all its generations..."

The existence of the great white cross was nationally publicized in the 1870s when tangible evidence was produced. In August 1873, U.S. Geological Survey teams under the leadership of the renowned F. V. Hayden made the first recorded summitings of both the Mount of the Holy Cross and Notch Mountain, giving western photographer William Henry Jackson the opportunity to take the first-ever photo of the "Cross Of Snow" from the latter vantage point. The next year, artist Thomas Moran went along on Hayden's follow-up expedition to the area, viewed the unusual cross for himself, and made a large oil painting of it. (This well-known painting is now exhibited in the Museum of the American West, a component of the Autry National Center in Los Angeles.)

In the summer of 1876 -- the summer that brought Custer's defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and an abrupt heightening of public interest in the western frontier -- both the Jackson photo and the Moran painting went on exhibit at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The photo, painting, and stories of the cross on the mountain created quite a stir. Though scarcely known to exist until just a few years before, the cross was now national news.

Pilgrimage Destination

With prompting from journalists, religious leaders, and others, including tourism promoters and regional business interests like the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, many Christians throughout the U.S. came to believe that the huge cross was actually a Holy Cross that God placed there on the mountainside as a sign to endorse Christianity, American power, western settlement, and related values. The Holy Cross was even believed to possess curative and restorative powers.

People began making trips to view the Holy Cross, and by the early 1920s there were organized pilgrimages. In the mid-1920s a tiny all-stone cabin was erected atop the southern ridge of Notch Mountain. Originally known as the Pilgrim's Hut (and still in use as the Notch Mountain Shelter), the sturdy little structure provided shelter from the alpine cold, a venue for Sunday mass, and a vantage point for viewing he Holy Cross, which is visible from the hut's window.

National Park System Tenure

The popularity of the Holy Cross generated a groundswell of support for federal protection of the site. On May 11, 1929, Herbert Hoover proclaimed Holy Cross National Monument and placed the new entity under U.S. Forest Service administration.

National Monument designation garnered additional publicity for the Holy Cross, and its popularity continued to grow. By the 1930s, thousands of pilgrims were flocking to see the Holy Cross, climb the Mount of the Holy Cross, or dip "holy water" from the Bowl of Tears Lake at the base of the cross.

It wasn't long before the Holy Cross was brought into the embrace of the National Park System. Holy Cross National Monument was one of 11 "scientific" National Monuments transferred from the National Forest Service to the National Park Service by executive order in the Reorganization of 1933 (effective August 10, 1933).

Boosters hoped that this administrative rearrangement would bring an infusion of financial support and infrastructure development, but in this they were mistaken. Like so many other small western NPS units in remote locations, Holy Cross languished. Except for a few improvements, most notably a log lodge that the Civilian Conservation Corps constructed in 1934, Holy Cross went through the Great Depression and World War II as one of the Park System's neglected stepchildren.

Decommissioning

By the late 1940s, declining pilgrimage activity, unreasonably high staffing expenses, and marring of the Holy Cross by rockslides and erosion (especially affecting the cross's "right arm") had diminished the viability of Holy Cross National Monument to the point that its continuation could not be justified. By Act of Congress effective August 3, 1950, the site was stripped of its National Monument designation, removed from the National Park System, and returned to the Forest Service for administration.

Ironically, a commemorative stamp issued in 1951 to honor Colorado's 75th Statehood Anniversary featured a collage of three Colorado icons -- the state Capitol, the Columbine (state flower), and the Holy Cross.

Update

Today, Mount of the Holy Cross is the visual centerpiece and a key recreational attraction of the Holy Cross Wilderness Area, a 120,000-acre tract that Congress added to the National Wilderness Preservation System in 1980. During the prime July through September hiking season, Notch Mountain is frequently summited, and so is Mount of the Holy Cross (now one of Colorado's most popular fourteeners). Neither is particular challenging -- they are scrambles, not technical climbs -- but hikers can lose their way if they aren't careful and must be prepared for abrupt weather changes. There are options for less strenuous recreational activities. The Tigiwon Lodge, which is located at the end of the graded, 2WD-accessible Tigiwon Road, is popular for a variety of recreational gatherings from picnics and family reunions to weddings. When winter arrives, snow sports reign. Snowmobiling is popular on the groomed tracks, including the winter-closed Tigiwon Road.

Postscript: Five other national parks that the National Park System acquired in the 1933 Reorganization were also abolished. Chattanooga National Cemetery was returned to War Department administration in 1944. Father Millett Cross National Monument -- the smallest National Monument ever established -- was abolished in 1949 and transferred to the state of New York. New Echota Marker National Memorial was abolished and transferred to the state of Georgia in 1950. In that same year, Colorado's Wheeler National Monument was abolished and the land was returned to the Forest Service for administration. Castle Pinckney National Monument was abolished in 1956 and transferred to the state of South Carolina.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

This may be regarded as heresy, but might it not be a good time now to inventory all our NPS areas with the eye toward some more pruning?

Perhaps if we considered cutting the inventory of some of our assorted parks, monuments, historic sites and whatever other monikers are out there, the Park Service might be able to actually properly care for those that are left.

Should monuments to past power brokers of various political stripe be Federal? Could many or even most of them -- such as LBJ or the new Clinton Birthplace -- be turned over to states or private entities? Should NPS be burdened with maintaining shrines to departed Presidents of any political persuasion other than those like Washington or Lincoln whose legacy was far greater than some others? (After all, Monticello, home of one of our most pivotal Presidents, is administered by a private foundation. And so is Mount Vernon.)

Is it time to acknowledge the possibility that at least some of our current assemblage of NPS administered sites might really be simply examples of Pork Barrel power grubbing rather than places of really national significance?

Y'know, if NPS could sell tickets to spectators to the fight that would certainly ensue, that might be a great fundraiser for the Service. Because if anyone can ever find the courage to actually try something like this, they'll set off the biggest battle since Bull Run or Gettysburg.

Lee-

Not heresy at all: I totally agree. You picked the right word: courage. Nobody has the courage to take a reasonable look at the national parks to find ones that maybe aren't of national significance. Add to my list: Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, Steamtown NHS, Minidoka NHS (already duplicated subject matter at Manzanar).

I wonder if park units are being created because they're convenient, not because they're an iconic, "national" example of a particular historic or natural feature. Is River Raisin a premier example of War of 1812 battlefield sites? Is it emblematic of the War of 1812? (Not the Battle of Lake Erie [Perry's Victory NMem] or the Battle of New Orleans?) I'd never heard of River Raisin. Or was this site convenient because the land was easily available?

But a fair question: will anyone have the courage to prune the national parks so that those that remain are true iconic representations of America?

To Lee and Chris - you both have said what I have thought and could not begin to say as eloquently. There are so many sites that are not of national importance, or even of importance, that could easily forego the budget and have it put to excellent use in our truly National Parks - Yosemite, Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and on and on. And yes, I never heard of River Raisin either before the article appeared here several weeks back and I thought "what the heck are they talking about". And lets face it - they were really stretching it to call this a place for NPS status. Also, birthplaces of Whoever should not be a national shrine, for crying out loud. Like you said - look at Mt Vernon. If any birthplace should be considered for NPS status, this would be it - the one and only. But I think alot depends on how bold and brash the senator/representative from each state is as to whether they get the federal funding for their little piece of importance back home. Some of these designated areas are an absolute joke to be included in an organization as grand as the National Park Service and what all it stood for at its creation.

Actually, Mt. Vernon is not Washington's birthplace. That IS an NPS area. (At least I think it is . . . . gonna have to double-check that.)

But your comment about "bold and brash" Congresscritters seeking "Federal funding for their little piece of importance back home" is right on.

I completely agree with these comments thus far. I would add the Vanderbilt Mansion to that list as it only became an NPS site because FDR didn't want the land adjacent to his home to fall to developers so it was sold to the NPS for $1.00 and a huge tax write off for the relative who inhereted it. There are so many other examples of guilded age mansions available to the public that are in much better condition.

OK, this is what I have come up with: Mt Vernon is not a National Park Service site. George Washington's birthplace is a National Park Service site at Colonial Beach, VA. Two entirely different entities and I must confess I never realized that. But I still cling to the notion that just because a president was born down the street doesn't mean the house should be a shrine forever more. After all, he's not Shrek!

Given the current direction of our great nation, it is not only a good idea to stoke up the NPS campfire, but to recognize that the pruning process has to take place soon. The NPS basket of diverse units weakens the founding concept of "national parks" and their unique role in American conservation. The management practice of changing basic park values and resource interpretaions away from the original, Congressional intent flies in the face of historic integrity and gradually weakens the understanding and support for the National Park System, in general.

As the son of a Park Service Landscape Architect (Blue Ridge Parkway) I at first was ready to disagree with this. But the concept of the states taking over the presidential sites preservation has a lot of merit. And the Park Service is definitely having issues maintaining the parks without the pork issues.

Everything needs to be on the table to minimize federal spending and to optimize what is kept.

Adopt a park folks!