Water.

There are some places where everything depends entirely upon the life-giving magic of water. It was water, or the lack thereof, that turned back some of the earliest Spanish explorers of the West and sent them home.

When the explorer priests, Fathers Dominguez and Escalante, headed west from Santa Fe in 1776, it was water that determined their routes. It was water that guided them northwest into what is now Utah. It was water that lured them toward the blue expanse of the place we call Utah Lake. And it was the absence of water that forced them back.

Back towards the southeast, down to places now connected by Interstates 15 and 70. Then east across a desolate dry land to their crossing of the Colorado River and back to the Spanish capital of Nuevo Mexico. As they turned east, they skirted along the northern edge of the chasm we call Grand Canyon.

It’s doubtful they realized it -- water -- was there, only a few miles south, as they struggled from one green spring to another across a land that even today is so empty it almost defies comprehension. The two padres would have climbed to high points to scan the route ahead, looking for tell-tale beacons of light green against an otherwise dark green or brown landscape.

Light green meant life. Water from a spring or a place where digging a shallow hole would bring water in a land where springs are hard to find and far apart. A land where today the lives of cattle and humans alike depend upon a few scattered windmill-powered deep wells that dribble water into tanks that hold it there for anyone or anything that needs it.

And it was water that drew Mormon settlers to a place that is still special today.

Emptiness Called The Arizona Strip

The Arizona Strip is still a desolate looking place. Lee Dalton photo.

The Arizona Strip is that expanse of mostly empty land north of the Grand Canyon. It is the bottom step of the geologic formation known as the Grand Staircase that climbs up to the colorful rocks of Bryce Canyon National Park.

In this arid land, water is as important as air itself when it comes to sustaining life. Early geologist Clarence Dutton wrote, “Pipe Spring is situated at the foot of . . . the Vermillion Cliffs, and is famous throughout southern Utah as a watering place. Its flow is copious and its water is the purest and best throughout that desolate region.”

Long before Dutton and his fellow Americans, before the Spaniards, Pipe Spring’s water supplied a long series of settlers and travelers. As early as 300 B.C., ancestors of present pueblo people lived, farmed, and traded with others around the shaded banks of Pipe Spring. But the time between 1000 and 1250 A.D. brought long drought that finally drove them from the land.

They were followed by Paiutes who had learned to adapt to the arid land and were able to support themselves and their families by living in small nomadic groups and making use of almost everything the dry environment offered. If there was any possible value to anything they found around them, they discovered ways to use it.

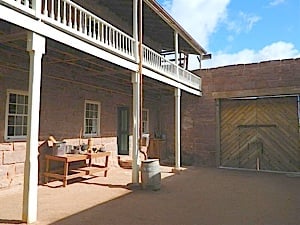

The courtyard at Pipe Spring. Lee Dalton photo.

At Pipe Spring, the Paiutes found a place where they were able to raise a few crops and were perhaps able to remain in almost permanent settlement.

Then came the Spanish Catholic explorers and missionaries. When the Fathers wandered by as they tried to find an easy route from Spanish settlements near Santa Fe to those in California, they probably owed their very survival to the Paiutes who provided food and directions that let them skirt the northern edge of the great canyon just to the south.

In 1858, Mormon missionary Jacob Hamblin stopped frequently at the spring. Famous explorer and surveyor John Wesley Powell was another who used the spring’s water several times in the 1870s. In the 1850s and -'60s, Mormon pioneers fanning out from settlements in the north and in St. George discovered the plentiful waters of Pipe Spring and moved cattle operations to the spring. Their livestock didn’t take long to decimate fragile resources Paiutes and Navajo had long depended on for life.

Communication with the world outside was provided by the telegraph at Pipe Spring. Photo by Lee Dalton.

In 1863, Mormon rancher James Whitmore gained title to lands around the spring and built a dugout shelter and some corrals. Conflict between the natives and encroaching whites led to bloodshed. Whitmore and one of his herdsmen were killed. Mormon militiamen built a small stone cabin near the spring for protection. Mormon church president Brigham Young sent more settlers south to grow cotton and sources of food were needed to support them.

One of the places chosen was Pipe Spring, where beef and diary products such as cheese and butter were produced for shipment to distant St. George. Anson Winsor was selected to run the ranch operation at the spring. In an effort to provide greater protection for his family and workers at the ranch, Winsor built two sandstone buildings that could serve as a fort. The spring was enclosed beneath one of the buildings for security.

The fort soon became known as “Winsor Castle.” The castle was a welcome and hospitable stopping place for travelers passing by. It became one of a number of stations on the new Deseret Telegraph where messages were received and relayed by skilled operators who could tap out and understand the dots and dashes of Morse Code. Later it became a place of refuge for polygamous Mormon wives who were being hunted by federal marshals as the United States tried to stamp out polygamy among Utah’s Mormons.

Enter The National Park Service

Finally, Pipe Spring caught the attention and intense interest of the first director of the National Park Service, Stephen T. Mather, who worked tirelessly until President Warren G. Harding proclaimed Pipe Spring a national monument in 1923.

It had been a long time since I had visited Pipe Spring, and when I stopped there in mid-March this year, I was curious to find what might have changed. I remembered a wide range of terrific living history demonstrations provided by local craftspersons and the monument’s staff when I’d been there years ago.

A more modern visitor center has been constructed, and the monument is now a joint effort between the NPS and Kaibab Paiute tribe. The day was cold with a ferocious wind blowing that chilled its way through even a good jacket and warm cap.

Pipe Spring is not on the main road to anywhere and even in summer it’s one of those quiet, peaceful places that make so many small sites like this such gems for anyone who discovers them. On this day, there was only one other visitor around when I walked out to the castle to meet Ranger Stephen Rudolph for a tour. When pressure of visitation is that low, schedules lose their importance and Ranger Rudolph was able to lead the two of us on a very personalized exploration of the fascinating stories found within those walls. His knowledge of the spring’s many tales seemed encyclopedic.

The telegraph was the best connection to the rest of the world. Lee Dalton photo.

He introduced us to some of the critters living there now to represent the cattle, chickens and other animals that were once such important parts of the Pipe Spring story. In fact, ducks and chickens range free just as they did more than a hundred years ago. Visitors are cautioned to watch out for bird poop on the trails.

Ranger Rudolph led us through the castle’s two stone buildings filled now with furniture and other essentials of frontier life. He wove stories of the people – men, women, children – who lived and passed by here long ago. We saw the cheese-making room down in a cellar cooled by the spring’s flow.

It wasn’t hard to imagine the clickity-clack of the telegraph key as a young woman received and relayed messages from one part of the growing territory to another. The ranger told us how the telegraph operators, who were mostly female, could listen to and pass along the latest gossip when they were off duty. How the telegraphers were the ones entrusted with confidences of all kinds – but who could still discuss it all among themselves because only they were able to understand the chattering code.

He told us of the cowboys who raised the cattle that gave the milk and provided meat for the men laboring to build a great white building that would become the first Mormon temple in Utah territory. He passed along the story of hospitality to all who passed this place and how people of all kinds shared bedrooms and beds with strangers who happened to be fellow travelers along the way.

There were stories of Indian raids. Of fear of attack. Of hardship almost unimaginable to us today that was simply part of the daily lives of those who passed here before us. We heard how Pipe Spring became a refuge for polygamous wives when their husbands were threatened with prison as the government tried to squash the “Mormon problem” in the 1870s and '80s.

Even now, not far down the road to the west lie the twin towns of Hilldale, Utah, and Colorado City, Arizona, where the population of “fundamentalist” Mormons still try to hang on to the practice of plural marriage.

I was reassured to learn that the living history I remembered so well from years past is still a vital part of telling the story of Pipe Spring – but only when weather is happier. Yet despite frostbitten ears and fingers so cold it was difficult to push the right buttons on my camera, there was no desire to rush through the place. But it did feel awfully good when we finally got back inside the warm visitor center.

Inside, out of the cold, the outpost was cozy. Lee Dalton photo.

A short interpretive film draws the whole story together, and gave me a chance to thaw out. The staff is busy and friendly. One of the women working for the cooperative association, Western National Parks Association, was busy cutting strips of cloth from worn clothing.

In summer, cowboys still brand cattle. A loom weaves woolen cloth and those strips of rags will become rugs. A blacksmith makes horseshoes and other implements needed to keep the ranch running, and the smell of baking bread wafts through rooms where this day only penetrating cold greeted us.

Pipe Spring is located along one of several possible routes from Zion National Park to the Grand Canyon’s north rim. It’s also part of the historic "Grand Circle" of national parks in southern Utah and northern Arizona — Zion, Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon and Cedar Breaks. A fine highway runs right past the monument, but it does take some effort to find and reach the place. It’s worth it, though.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

We visited Pipe Spring a couple of weeks ago and enjoyed it immensely. The author is correct that it receives very few visitors and that is exactly what was so nice about the place. That, and the very dedicated, informed and friendly staff. Pipe Spring is a true oasis in the desert. It is well worth a couple of hours visitation.