Editor's note: A much publicized conference, Science for Parks, Parks for Science: The Next Century, opens today at the University of California, Berkeley. Led by the National Park Service and National Geographic Society, conference sponsors propose 'to launch a Second Century of stewardship for the parks, 100 years after the historic meetings at UC Berkeley that helped launch the National Park Service.' A specialist on those meetings of 100 years ago, Alfred Runte reports for the Traveler why the story does not end there.

Here billing itself as the National Association of National Park

Superintendents, the National Park Conference of 1915 poses before the

Southern Pacific Railroad Building at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Stephen T. Mather (light coat, dark hat) stands in the front row, 12th from the left. His assistant (and eventual successor) Horace M. Albright (dark suit and hat, holding

coat) is 7th from the left. In all, the conference registered 73 participants. Of the 53 people pictured here, one or two are likely railroad officials/Library of Congress

As the holder of a Ph.D. from the University of California, I obviously take note when one of its campuses lays claim to a 'historic' moment. As is the case today, March 25, 2015, in a conference recognizing the relationship between science and the national parks. For the next three days, scientists from across the nation will be meeting at UC Berkeley. As heralded on the conference website and in a Park Service news release, the meeting occurs 'exactly a century after an historic conference at Cal brought together scientists, conservationists and park leaders to focus on the need for a federal agency to manage park science, stewardship and public engagement. The March 1915 gathering catalyzed the formation of the National Park Service one year later.'

In fact, the history of the 'gathering' is far more complicated, and indeed, far less about science than these words suggest. For starters, the National Park Conference (its official name) was already the third in a government series. The first, called by Secretary of the Interior Walter L. Fisher, met at Yellowstone in September 1911. He then presided over an identical meeting in Yosemite National Park in October 1912, referring to it as the 'Second Annual National Park Conference.' In 1915, as assistant to Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane, Stephen T. Mather called for the third meeting at UC Berkeley, although not, as the Park Service implies today, specifically to form a lasting relationship with the university on behalf of 'managing' science.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition

Better said, Mather's inspiration lay across San Francisco Bay. In 1914, the United States had brought to completion the building of the Panama Canal. In commemoration, the U.S. Congress had chosen San Francisco as the site of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE). Yet a second world's fair, the Panama-California Exposition, was running concurrently in San Diego. Although both were elaborate undertakings, the PPIE was the official national fair, including one square mile of buildings and exhibits stretching from Fort Mason to the Presidio (the Marina District). Still surviving in its original location, the Palace of Fine Arts reminds us what a spectacular fair it was.

The point is that the National Park Conference of 1915 was inspired entirely by the PPIE. Both at the conference and at the fair itself, the principal participants were America's railroads as the parks' major concessionaires. Although a sprinkling of scientists (and conservationists) attended the UC conference, Berkeley listed only one. With that exception (a self-described botanist), the few scientists were government foresters invited to detail the ravages of forest insects. Their presentations may have sounded 'scientific'; however, they proposed manipulation in the interest of protecting scenery, speaking entirely to the need for 'salvage' logging to rid infested areas of 'unsightly' trees.

In short, as in 1911 and 1912, still the principal discussion at the 1915 conference involved promoting the national parks as vacation resorts. When approved, the National Park Service would help streamline park development. With World War I gripping Europe, the railroads especially saw their chance. Finally, their long-standing 'See America First' campaign might be realized now that Americans no longer felt safe abroad.

Union Pacific's Yellowstone exhibit at the PPIE included a horse-drawn tour.

Imagine the boost such images--in this case a promotional postcard--gave to

the National Park Service bill/Runte Collection

In today's dollars, the railroads spent an estimated $100 million mounting their buildings and exhibits at the fair. Sprawled across more than four acres of the fairgrounds known as 'The Zone,' the Union Pacific was modeling Yellowstone, complete with a full-size replica of Old Faithful Inn. Encompassing six acres, mostly indoors, the Santa Fe Railway was modeling Grand Canyon and giving 'parlor car' tours along the rim. The train ride lasted 30 minutes and stopped at seven of the 'grandest points.' The palatial, columned building of the Southern Pacific Railroad featured Yosemite Valley and the giant sequoias. At the Great Northern Railway Building, Blackfeet Indians in full ceremonial dress played host to exhibits of Glacier National Park.

The Conferees at the PPIE

On its third and final day, the National Park Conference itself moved from California Hall on the UC campus to the auditorium of the Southern Pacific Building. Conferees then lunched at Old Faithful Inn'exact in every detail to the actual lodge in Yellowstone (and twice the cost), but now a huge restaurant seating 2,000 guests. An 80-piece orchestra gave afternoon and evening concerts. Afterwards, visitors might stroll over to the 1,000-seat Spectatorium, where a replica of Old Faithful Geyser played. 'All of a sudden it shows signs of life. It grumbles a little. It throws out a puff of smoke, then a jet of water, followed quickly by another. Then a mighty roar fills the auditorium and the heavy artillery of 'Old Faithful' goes into action. A mighty column of boiling water is lifted by successive upheavals to the apparent height of 150 feet and the attendant rush of steam obscures the sky.'

Above lay Eagle Nest Rock, overlooking the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The 'Great Falls of the Yellowstone' completed the spectacle, that is, if by some chance (very remote) anyone had missed the great relief map fronting the Inn. 'If one could fly ten miles above the real Yellowstone Park, equipped with a field-glass powerful enough to overcome the distance, he would get the sort of view of Yellowstone which this topographical map affords,' the Union Pacific wrote. Fashioned of painted cement, highlights included 'the important geyser and other plutonic formations; hot springs, roaring mountains, lakes, falls, cascades, grottoes, government roads, trails and other outlines; so correctly located that any one familiar with the Park can readily point out the roadways taken by him, as well as all the important natural wonders which astound and electrify tourists. Nothing to compare with it was ever before attempted on so large a scale'somewhat more than one acre in area.'

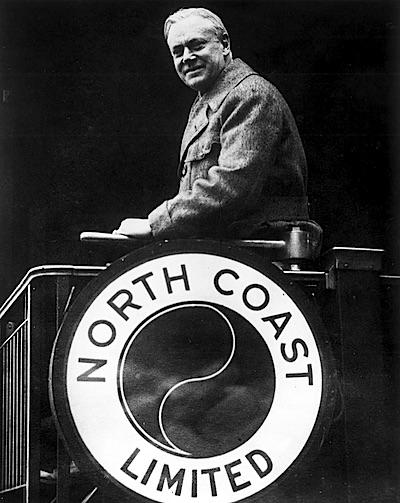

Although the first director of the National Park Service, Stephen T. Mather was by no means the founder of the agency. Many civic leaders share that honor. Here he gives tacit credit to their critical allies--the railroads of the American West. Mather valued and knew them all, in this case, the

Northern Pacific Railway as operators of the celebrated "North Coast Limited" (Chicago-Seattle). Likely Mather's train will itself split at Livingston, Montana, offering through service to Yellowstone National Park via Gardiner/National Archives

Only recently appointed to the Interior Department, Mather realized he was a late-comer to the party. The proposed National Park Service needed a rallying cry, and suddenly, the railroads were doing all of the rallying. Beginning several years before the PPIE, they had already unleashed a torrent of specialty advertising. Seeking legitimacy of his own, Mather then looked to UC for a forum that would link him to the PPIE.

He acknowledged as much in his opening remarks. 'When I asked Secretary Lane if I could hold a conference of the park superintendents, of which two had already been held in previous years, 1911 and 1912, my thought naturally turned here to Berkeley. I felt that here was the place, especially this year, with the thoughts of the country on the great exposition, to hold this conference, and that this would be the natural place for all of the superintendents to come. When I telegraphed out here and asked permission of President Wheeler to use one of the university buildings, or one of the halls for this purpose, he responded most heartily.'

A Berkeley alumnus, Mather next prevailed on his fraternity brothers to provide the conference with sufficient lodging. 'I want to thank also the members of my own fraternity [Sigma Chi], who so willingly threw open their house as an abiding place for our superintendents, supervisors, and members of the official party from Washington. . . . The boys in this case gave up their house and went elsewhere, and gave us the opportunity to have that peculiar home life that otherwise we could not enjoy.'

In other words, Mather's 'partnership' with UC was a plea for space. That may sound cynical, but consider the PPIE. How many hotel rooms were left in the Bay Area for a conference of any size?

As for science, it remained for UC President Benjamin Ide Wheeler to showcase the university's intellectual accomplishments, including its biological station, forestry station, farm school, Lick Observatory, and now fledgling campuses across the state. 'The concept of the university has grown in years enormously,' he noted. 'We are no longer training callow boys who are spending four years of rollicking.' Instead, Wheeler was proud to note that UC was evolving into a 'community.' 'We are trying to do the best we know how. We give you all a hearty welcome here.'

The point remains that by 'you all' he still spoke to a preponderance of business interests bent on developing the national parks. James K. Moffitt, a UC regent, further listed 'engineering, botany, geology, forestry, and entomology,' along 'with the love of the mountains' for which UC was renowned. But that again was sidebar to Mather's purpose. As in 1911 and 1912, he insisted the conference stay on message about improving the parks as destination resorts.

There especially, the PPIE was the catalyst'the truly 'historic' moment of 1915. By then, there was nothing new about a meeting of park superintendents, or for that matter, the Park Service bill. It, too, was five years old. Although its originators had made little progress, Stephen Mather realized he was about to stall himself. 'Science' would never break the logjam in Congress. He rather needed the railroads and the PPIE.

Imagine up to three years of preliminary advertising on a par with Super Bowl Sunday. Imagine playing the game itself before an average of 65,000 spectators, not once but over 270 days. During those nine months, visitors clicked the turnstiles nearly 19 million times. Even accounting for the many repeats, an estimated five percent of the country saw the PPIE in person.

Like Yellowstone by the Union Pacific Railroad, the Santa Fe Railway's

exhibit of Grand Canyon received accolades for its true-to-life colors and

rich details. Unfortunately, high-speed film was still in its infancy, to

say nothing of color film. At least we have this rare interior view to

confirm what millions of fairgoers saw. Then imagine what they impressed on

their fellow Americans, and how that unlimited stream of publicity helped

promote the Park Service bill/Fred Harvey Collection, University of Arizona

Archives.

The National Park Service did not hang on a government conference'or a university conference. It rather hung on the PPIE. Thanks to the railroads and their exhibits, henceforth no one in Congress could deny what Americans wanted for the future of their parks.

Why does the Park Service forget this today'and the National Geographic Society? And the University of California? Because Mather's biographers got to the history first, and made sure the focus stayed on him. Consequently, the Park Service continues to celebrate its history still believing that Mather 'did it all.' He was a major player, no doubt about it, but in this case the rest is legend. So is the web page proclaiming UC Berkeley as the 'birthplace' of the 'National Park Service idea.' No.

Why should we even need a birthplace? However, since apparently some people do, it would legitimately be the offices of the American Civic Association, headquartered in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. In those offices would be found J. Horace McFarland, who proposed the agency in 1910.

Afterwards, many distinguished Americans campaigned for the National Park Service, including President William Howard Taft. As to why they remain at the bottom of the storyline, again, think Mather's biographers. Their preferred 'historic' event is the so-called Mather Mountain Party. Certainly, those 20-some people he took through Sequoia National Park two months after the Berkeley conference figured prominently in promoting parks. But 20 people compared to the PPIE? Now you know the problem with writing history when a legend gets to it first.

Still to allow ourselves to forget the greater history is to forget what the National Park Service really is'and needs. It was always America's creation, as were the parks themselves. If UC and the Park Service want to talk about a 'historic' gathering, they should start with the PPIE. The National Park Service won America's heart in San Francisco, where Old Faithful the Second gushed on cue.

Joseph Grinnell and the Science of Sanctuary

Joseph Grinnell in the field. By 1915, when this picture was taken, he was already an outspoken champion of predators/ Wikimedia Commons

Science was still in the wings'and still, because it challenged development, destined to be marginalized for decades to come. Indeed, because scientists preferred not to alter the national parks, they and the Park Service would find themselves at constant odds. When science did enter the picture, yes, the major contributor was at UC. But there was little mention of his skills in 1915. For the contributor was himself a critic of the Interior Department, the zoologist Joseph Grinnell.

Already intimately familiar with California's flora and fauna, in 1908 he was appointed director of UC's new Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. After completing his Ph.D. at Stanford in 1913, he applied to the U.S. Department of the Interior for permission to conduct a transect of Yosemite National Park, as he proposed to Secretary Franklin K. Lane, 'along a line through Yosemite from Merced Falls to Mono Lake.' The objective of the survey included the identification of all mammals, birds, and reptiles, with special attention to their ecological relationships; 'in other words,' Grinnell elaborated, 'their natural history.'

Throughout his career, Grinnell's springboard to the national parks remained Yosemite. With a colleague, Tracy I. Storer, he then disclosed his ideas for all of the parks in a major article for Science magazine. The date of publication was September 15, 1916, barely three weeks after the National Park Service had been approved.

Although diplomatic, the article was critical, and not what the Interior Department wanted to hear. The title said it all: Animal Life as an Asset of National Parks. The national parks were more than scenery and a business opportunity for the tourist industry. The deeper object of preservation was to educate the public to enjoy the totality of the natural world.

That meant ecology as well as mountain tops. The national parks in fact were universities of the wilderness in which all flora and fauna should claim a refuge. 'As settlement of the country progresses,' Grinnell and Storer elaborated, 'and the original aspect of nature is altered, the national parks will probably be the only areas remaining unspoiled for scientific study.'

Although a national park, Yosemite regularly called on California's official

lion hunter, Jay Bruce, to eradicate predators from the backcountry. Here

Bruce poses in front of the valley administration building in 1927. Joseph

Grinnell finally succeeded in ending the practice in 1931/Yosemite National

Park Research Library

Here Grinnell threw down the gauntlet. 'It almost goes without saying that the administration should strictly prohibit the hunting and trapping of any wild animals within the park limits. A justifiable exception may be made when specimens are required for scientific purposes by authorized representatives of public institutions.' Otherwise, 'as a rule,' even 'predaceous animals should be left unmolested and allowed to retain their primitive relation to the rest of the fauna.'

The true objective of the national parks was not recreation as such, but rather that form of recreation allowing the parks to serve as refuges of biological diversity. Only the national parks, Grinnell and Storer reemphasized, held forth the hope of preserving for scientists'and the American people''samples of the earth as it was before the advent of the white man.'

Although their wording may now be dated, their science was sincere. Predators especially deserved the government's care. There remained no possible rationale for eliminating them other than human prejudice. Besides, 'many of the predatory animals like the marten, the fisher, the fox, and the golden eagle, are themselves exceedingly interesting members of the fauna, and as their numbers are already kept within proper limits by the available food supply, nothing is to be gained by reducing it still further.'

Stephen Mather would never agree. He rather insisted that the national parks be cleared of predators, and persisted until most were gone. Repeatedly, Joseph Grinnell's letters abhorring the practice of killing predators languished on Mather's desk.

A person of lesser conviction might have been discouraged; Grinnell knew human nature. A precedent'however small'is not easily overturned. Obviously, he needed to make precedent of his own. For the next 25 years, he perfected concise, well-worded letters arguing the points he wished to make. Defending predators, he would gently prod, then diplomatically back off, then gently prod again.

'I wish to repeat my belief,' he thus wrote the acting superintendent of Yosemite in 1927, 'that it is wrong to kill mountain lions within Yosemite, or within any other of our National Parks of large area. They belong there (emphasis his), as part of the perfectly normal, native fauna, to the presence of which the population of other native animals such as the deer is adjusted.'

The reasonable exceptions were obvious. Other than individual animals posing an actual threat to visitors, there was no excuse for what appeared to be a purposeful relaxation of national park philosophy. 'It would seem to me,' he repeated, 'that national parks should comprise pieces of the country in which natural conditions are to be left altogether undisturbed by man. The greatest value of parks from both a scientific and recreational standpoint will thereby be conserved.'

Well into the 1930s, Grinnell's ultimate strategy was to 'infiltrate' the Park Service with his best and brightest students. From Harold C. Bryant to George M. Wright, UC can deservedly take pride in those students. That said, the fact remains that they'like Grinnell'were the ones who took the risk. The persistence necessary was entirely personal. Bureaucracies do not like people making waves.

Grinnell especially was UC's Student Placement Center, pleading repeatedly with his students to take any job with the Park Service just to get a foot in the door. He thus wrote Harold Bryant in 1919: 'The main thing is to get a precedent set.' In this case, the precedent uppermost on Grinnell's mind was a natural field guide service in Yosemite Valley. Bryant and a colleague started with the Park Service the following year, much to Grinnell's delight'and relief.

The Foundations of Interpretation

To be sure, he had dogged Stephen Mather on the subject ever since his article with Tracy Storer in Science magazine. After securing the parks for science, they asked 'that provision be made in every large national park for a trained resident naturalist who, as a member of the park staff, would look after the interests of the animal life of the region and aid in making it known to the public.' Grinnell then elaborated to Mather that Yosemite would be the perfect venue for 'a natural history leader or guide' who would 'be available for service at the several public camps in the Valley, particularly those with the largest registration, such as Camp Curry.'

Of course, Grinnell modeled his exemplary guide after what he expected from his students. The guide should have 'the highest standing as a biologist,' be of a 'pleasing personality,' and be 'a facile and polished speaker.' In short, 'he should not (italics his) be a casual pick-up, of unpolished language and manner.' The leader or guide would 'give twenty minute evening talks on local natural history'birds, mammals, reptiles, fishes, forests, flowers'perhaps two or even three such talks could be given at different centers in one evening.'

As featured on the cover of this Union Pacific Railroad brochure, the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition inspired the transcontinental railroads to contribute stunning exhibits of the national parks. Now San Francisco's Marina District, the fairgrounds encompassed an entire square mile, four acres of which Union Pacific turned into Yellowstone National Park./Runte Collection.

Again, only because Mather's biographers have written a 'protective' storyline has the deeper history of these events been suppressed. Science was not on his agenda in 1915, or for that matter when he left the Park Service in 1929. To be sure, spotlighting Joseph Grinnell's defense of predators alone, science arguably did not become a Park Service priority until 1995, when wolves were returned to Yellowstone.

That is 79 years past the agency's founding. The point remains that if the Park Service wants a truthful history, it needs to recognize that professional historians may in fact interpret delay as opposition. Was science a priority in 1915? Or in 1916 when the Park Service was established? No, unless the countless documents I have examined in Berkeley's archives were put there to mislead.

Mather's singular priority was the agency, and there he could see it, too. He needed the railroads to push the Park Service over the top. Anything less spectacular, as in academic, would allow Congress to stall and flounder. He was not at UC to pursue an academic defense of the national parks but rather to court real power. Across the country and at the PPIE, the railroads were wielding power. Never had any fair, let alone a world's fair, so confirmed the popularity of the national parks.

In asking that the spotlight remain on a limited narrative, we only admit that the greater narrative is beyond our grasp. Where is our Panama Canal? Where is our PPIE? Where is our celebration of American greatness? For that matter, where are the railroads that once loved the parks? Any corporation can write a check and claim philanthropy. The railroads once believed in the parks, is the point.

No wonder we ask history to support our foibles. Looking back too honestly, we might see too clearly exactly what we have lost. Was America a perfect country in 1915? Far from it. But at least America knew it was on its way.

If 2015 were anything like 1915, we would know what to celebrate'and what not to miss. Nor would we exaggerate for effect. Now we see it. Science and the national parks are indeed a natural. It is just that few Americans saw it then. As for the Park Service, it needed a boost from industry'and got it'on the wondrous grounds of the PPIE. That was the catalyst for the National Park Service'the perfection'that the nation knew not to squander.

Will the country ever be that optimistic again? I hope so, because nothing idealistic can survive without it. Our current cultural malaise defies optimism. Only a true catalyst'a true reawakening'can possibly renew what it means to teach, love, and protect 'the best idea we ever had.'

____________

A frequent contributor to National Parks Traveler, Alfred Runte holds a Ph.D. in American Environmental History from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he specialized in the national parks. His article here is derived from his research at the University of California, Berkeley, for three of his books: National Parks: The American Experience (4 editions, 1979-2010); Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness (1990), and; Trains of Discovery: Railroads and the Legacy of Our National Parks (5 editions, 1984-2011).

___________

A Look Back At The Panama-Pacific International Exposition

Featured here in a promotional postcard, the Southern Pacific Railroad

Building at the Panama-Pacific Exposition hosted the third day of the

National Park Conference of 1915. Popular exhibits included Yosemite and the

giant sequoias/Runte collection

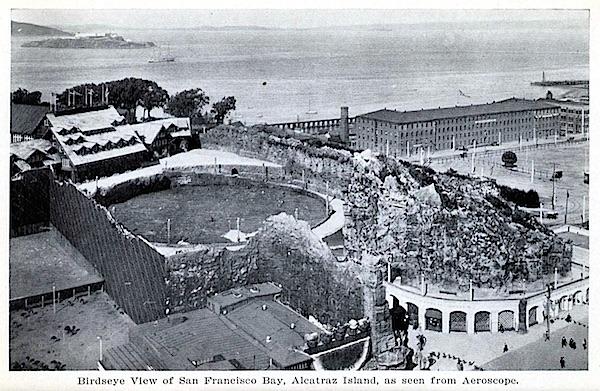

On a site that otherwise would have allowed a spectacular view of San

Francisco Bay, Union Pacific's massive Yellowstone exhibit at the PPIE drew

19 million visitors. Note Alcatraz Island in the background over the top of

Old Faithful Inn/Runte Collection

Fairgoers entering the Great Northern Railway Building received this

promotional postcard from their Blackfeet hosts. The back of the postcard

reads in part: "Visit Glacier National Park. Where mountains surround and

beauties abound."/Runte Collection

Using dioramas to simulate a transcontinental railroad journey in miniature,

The Globe was the product of four western railroads hoping to attract more

tourists west. Note how the exterior of the exhibit, mapping possible

routes, prominently features Yellowstone./Runte Collection

No less popular than Union Pacific's Yellowstone, the Santa Fe Railway's

massive indoor model of the Grand Canyon included a Pueblo Indian village on

the roof./Runte Collection

Afternoon and evening concerts at the Old Faithful Inn featured an 80-piece

orchestra. Arriving guests received this program/Runte Collection

Comments

Thank you Dr. Runte. Truly an outstanding article. However, I would say that science played a role much earlier in the NPS history than the 1990's. I think of George Wright's introduction of the idea of an ecoystem approach to park managment during the 1930's, the "Leopold Report" of the early 1960's, the introduction of fire as a management tool to protect seedling germination in groves of giant sequoia in Yosemite and Sequoia Kings Canyon National Parks during the 1960's and 1970's with research of Drs. Hartesveldt, Shellhammer, Harvey, Briswell and others. In fact, there was a time when the Chief Naturalist was the second most important member of the NPS staff in a park, second only to the park superintendent.

Agree, an excellent, well written story, Dr. Runte.

Yes, Owen, I recall SEKI had a truly

outstanding Chief Naturalist, Russ Grater, whom I had met when Russ was working

out of Harpers Ferry, W Va., prior to arriving at SEKI. We witnessed the pioneering

fire ecological contributions of Dick Hartesveldt and his research team from

San Jose. State Univ. Ron Stecker was their entomologist who discovered the insect

boring into the peduncle or stem of the green giant sequoia seed cone causing it to

dry and shed seeds, hopefully on recently burned forest floor devoid of thick litter.

Dick Hartesveldt realized that old sequoias were growing well following

fire in Yosemite during his tree ring studies of Human Impacts on giant sequoia

groves.

Early in their field work, giant sequoia seedlings following prescribed

research burns were actually numbered by stakes until the entire sunlit unit looked

like a green lawn of thousands of seedlings.

http://www.nps.gov/seki/learn/nature/upload/hh_tt67.pdf

http://www.bandbbooks.com/giant-sequoias-by-hartesveldt--harvey--shellha...

Dr. H. Biswell was with the Univ. of Calif., Berkeley,

researching landscape visual effects of fire at Whitakers Forest. beyond the ridge

of Redwood Mtn. Grove.

http://www.fs.fed.us/psw/publications/documents/psw_gtr158/psw_gtr158_01_vanwagtendonk.pdf

Thank you Dr. Runte and thanks also to Owen and ml3cli for their comments. I must agree, science is an important aspect of many National Parks. Owen and ml3cli pointed it out well and there are many more excellent examples. Dr, Runte, an issue here is that science presents the best evidence available on a subject, the information then enters into the public discourse and then the political arena. Science has little say in the final political decisions in many cases. Often times the objections are based on little knowledge of the issue or a simple resistance to change for many reasons. Whatever the public perception is that is pandered to by many of those running for office, or in office, is a difficult hurdle to cross. A very interesting recent issue is the new Golden Gate National Recreation Area Dog Management Plan. It will be interesting to see how it turns out.

Perhaps another scientist worthy of mention was Dr. John C. Merriam. J. C. Merriam, who studied at UC Berkeley under Prof. Joseph LeConte, had a pioneering influence on the promotion of national parks as outdoor universities and centers of education in the disciplines of natural history and geology. He was also influential in founding the Save the Redwoods League.

http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520241671

A provocative article, Al. We need to meet over brandy someday to discuss it.

Cheers,

Don Scott