Franklin Roosevelt’s popular New Deal conservation program, which had a transformative effect on the nation’s parklands and the young men who filled its ranks, began 85 years ago.

“National Parks of the Country Will Ring with Sound of Conservation Workers.”

So read a headline in the May 20, 1933, edition of the Happy Days newspaper, the official publication of the newly formed Civilian Conservation Corps. And it was true: Established in March of that year, the corps became the most popular and enduring of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal “make-work” programs. It sent thousands of young men across the country to establish camps, create parks, plant forests, and construct roads, trails, shelters, and picnic areas. The CCC’s profound impact on the National Park System, as well as numerous state park systems, can still be felt today, 85 years after its founding.

Although the program was initially called Emergency Conservation Work, it quickly became known as the CCC by the press and nearly everyone involved. It was an early, bold step for the Roosevelt administration, a test of government dollars during the Great Depression. The program was designed to lift up an economically challenged nation, with $25 out of a CCC man’s $30 monthly paycheck automatically sent home to his family. “The eye of the nation is upon the Civilian Conservation Corps,” said ECW Director Robert Fechner early in his tenure. “The young men who make up its ranks are on trial, so to speak, with the whole country.”

Over the next nine years, more than two million boys and men joined the CCC in all 50 states. Although the official entry age was 18, recruits were often younger; the upper age limit was 25. Some would leave the CCC and go directly into the military, especially at the outbreak of World War II. They were well-prepared to do so, as the camps were initially operated by the U.S. Army and run with militaristic precision.

The first CCC camp was pitched in George Washington National Forest near Luray, Virginia, with the first national park camps opening soon afterwards in the Skyland and Big Meadows areas of what would become Shenandoah National Park. In 1933, along with his U.S. Forest Service counterpart Robert Y. Stuart, NPS Director Horace Albright was eager to use the new workforce and had infrastructure and reforestation plans ready before the first men left their hometowns. Eventually, CCC camps stood in nearly every major national park, as well as in numerous battlefields and national monuments. The National Park Service also used CCC personnel and funds to help states set up their own park systems. In total, although not all would last the entire nine-year run of the program, 841 CCC camps were established in the national parks, and 2,500 more were set up in state parks.

For the boys themselves, the CCC offered a steady income, regular meals, shelter, and the promise of hard work, which weren’t always givens during the Depression, when the country was facing a 25 percent unemployment rate. Early reports home were often that the men were gaining weight and making what would become, for many, lifelong friends. Marriages happened too, as CCC boys were known to socialize on their nights off with young ladies from nearby towns. (“Workers Divide Time with Pennsy Girls,” wrote one Happy Days article.)

In July 1933, the National Park Service sent one of its editors, Elizabeth Pitt, to tour camps in several Western national parks, including Yellowstone, Rocky Mountain, and Glacier. “Everywhere I have found the same spirit,” Pitt wrote afterwards, “boys from the East, for the most part, dropped down in the wilds of the mountains and taking hold of things like veterans of the woods.”

“With the right leadership and resources and the willingness to compromise and work together, more can be accomplished than we ever thought possible,” says Robert W. Audretsch, a former NPS ranger who has written several books about the CCC in Arizona and Colorado, including Shaping the Park and Saving the Boys: The Civilian Conservation Corps in the Grand Canyon. “With the CCC and other New Deal programs, as much as 50 years’ worth of conservation work was accomplished in national parks in less than ten years.”

Many CCC-built structures have long disappeared. But some remain in many national parks, and most parks find ways to share their CCC history through markers, ranger programs, and online and printed materials. In this anniversary year, you can visit these and other sites and remember the strong young men who changed the parks for the better.

"Iron Mike" stands in honor of the millions of CCC workers at the Byrd Visitor Center in Shenandoah National Park/NPS

Shenandoah National Park, Virginia

Director Fechner personally inspected the Big Meadows camp in 1933. As a newspaper account recalled, “Young men conducting their own religious services, maintaining their own morale, and carrying on the work prescribed for them with dispatch and initiative made a deep impression on him.” Today, though relatively hidden in the meadow’s northeast corner, the ghostly outlines of the CCC camp remain visible. Although no buildings remain, the NPS has staked the perimeters of some, such as the former mess hall, and included historical markers to describe camp life. Directly across Skyline Drive, the bare-chested statue of a CCC man, known as “Iron Mike,” stands in front of the Byrd Visitor Center, which also includes several exhibits about the CCC. The Pocosin Cabin, located on the Appalachian Trail, is also a well-preserved example of the CCC’s handiwork.

Acadia National Park, Maine

Hugging the shoreline near Sand Beach, the Ocean Path is one of Acadia’s most pleasant hikes, taking visitors near Thunder Hole, where the surf rushes loudly into a hole in the rocks, and on to the scenic Otter Point. This is also one of the CCC’s enduring projects. Other work on park trails included the Perpendicular Trail, where workers moved and cut large granite blocks and deftly put them into place. Crews also helped with firefighting and fuel reduction in the park, and constructed the Blackwoods and Seawall campgrounds. Today, ranger programs will often mention the CCC, and a plaque commemorating the crews can be found at McFarland Hill.

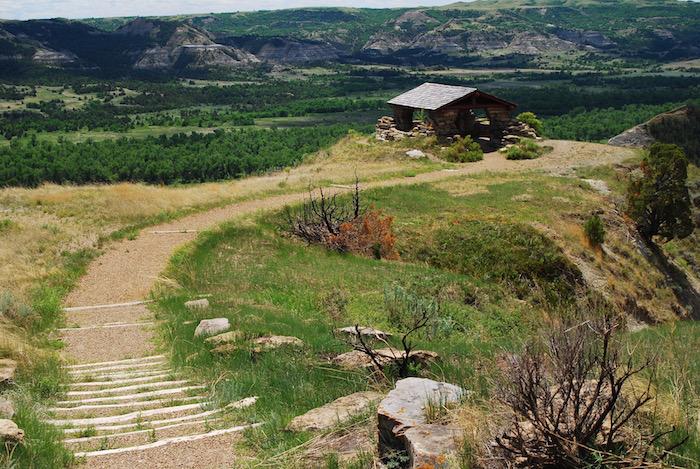

The River Bend Overlook in Theodore Roosevelt National Park provides sweeping views of the park’s badlands and Little Missouri River/Kurt Repanshek

Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

It is an interesting historical irony that CCC workers operating under the auspices of one Roosevelt would work on parkland that would eventually honor another. Beginning in 1934, the CCC built shelters and buildings in the North Dakota badlands that would become Theodore Roosevelt National Park in 1947. Theodore Roosevelt was Franklin’s fifth cousin and uncle of his wife, Eleanor. Today, their work stands in the form of two picnic shelters in the Juniper campground area, and the rustic River Bend Overlook shelter, high above the Little Missouri River.

Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

The Painted Desert Inn, a national historic landmark, is one of the most distinctive extant buildings associated with the CCC in the National Park System. When the NPS acquired the Stone Tree House, a circa-1920s tourist attraction made of petrified wood, in the 1930s, the CCC provided the perfect workforce to upgrade the structure. Working with well-known Pueblo Revival architect Lyle Bennett, the CCC men helped to reinforce and redesign the inn, hand-making light fixtures from punched tin, crafting wooden tables and chairs in a Southwestern style, and painting skylight panels to mimic prehistoric pottery. The inn also features the work of renowned Southwestern architect Mary Colter and murals by Hopi artist Fred Kabotie. Despite its historical significance, however, the inn faced demolition in the 1970s until it was saved by a public-relations campaign.

Skylights in the Painted Desert Inn were painted by CCC crews/Kurt Repanshek

Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

The imprint of the CCC can be found in many places at the Grand Canyon, which was home to seven camps between 1933 and 1942. The park has a walking tour brochure that outlines several places where you can view the CCC’s contributions, which include the stone stairway near the Kolb Studio, the Grand Canyon Community Building, and a pair of wooden bridges along the Village Loop Road. A rock wall along the rim near the El Tovar Hotel is also the CCC’s creation, and it features a surprise for eagle-eyed visitors, according to author Robert Audretsch.

Almost as proof of the heart they put into their work is this heart-shaped rock built into a rock wall on Grand Canyon’s South Rim / NPS

“My favorite spot along the wall is opposite where the Fred Harvey Women's Dormitory used to be located,” Audretsch says. “Here there is a stone carved in the shape of a heart, the only stone in the whole wall not shaped like a box, rectangle or diamond. Was it carved by some love-struck CCC boy? We will never know.”

“Congratulations are due those responsible for the gigantic task of creating the camps, arranging for the enlistments, and for launching the greatest peacetime movement this country has ever seen.” -- Franklin Roosevelt, after reviewing the earliest CCC camps

Traveler postscript: We’d love to hear from former CCC workers, or their relatives, so we could collect more of their stories. Please contact [email protected]