Wing of Western Small-footed myotis (Myotis ciliolabrum) under ultraviolet light. The orange fluorescence on the wing is characteristic of infection by Pd. Peter Kienzler, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database

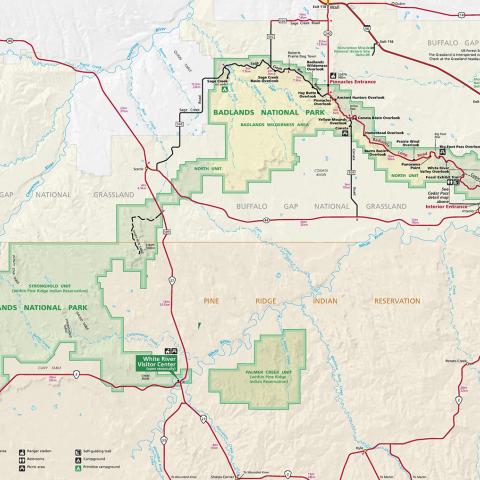

A fungus that causes white-nose syndrome, a deadly disease of bats, has been detected on bats in South Dakota for the first time. The fungus was detected on one Western Small-footed bat (Myotis ciliolabrum) and four Big Brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) in Jackson County at Badlands National Park in May.

The fungus was spotted on May 10 during proactive WNS testing conducted by the National Park Service Northern Great Plains Network in collaboration with the University of Wyoming. This is also the first known detection of the fungus on a Western Small-footed bat. Current evidence indicates that WNS is not a direct health risk for humans.

Bats are important for healthy ecosystems and contribute at least $3 billion annually to the U.S. agriculture economy through pest control and pollination. WNS has killed millions of bats in North America —with mortality rates of up to 100 percent observed at some colonies—since it was first seen in New York in 2006. To date, WNS has been confirmed in bats from 32 states and seven Canadian provinces. South Dakota joins Mississippi and Texas as states that have detected Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd) but not confirmed WNS. WNS drew its name from the powdery, white Pd growth that often appears around infected bats’ muzzles.

The fungus was detected in South Dakota during field examination of live bats using ultraviolet light and swab samples sent to the Colorado State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for testing. Those results were repeated in follow-up tests by the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center. While these results confirm the presence of the fungus, they do not confirm the WNS disease, which can only be confirmed by microscopic examination of tissue samples. Tissue samples were not taken during this sampling.

“The early detection of the fungus in South Dakota was the result of collaborative efforts made possible by a National Plan to respond to white-nose syndrome,” said Jeremy Coleman, National White-nose Syndrome Coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which leads the national response to WNS. “As the disease continues to spread across North America, biologists from many agencies are working together to prepare for and detect Pd as soon as possible and are ready to respond.”

The National Park Service supported the operation with funds dedicated to WNS response in national parks to actively protect bats and their habitats.

The National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, USGS National Wildlife Health Center, University of Wyoming, and South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks will continue to work together to screen for Pd and WNS in South Dakota.

“Because these bats were captured after they emerged from winter hibernation, we don’t know where they came from or where these individual bats encountered the fungus,” said Silka Kempema, biologist with South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. “We’d like to find that out.”

Pd affects bats while they are hibernating. Bats can disperse hundreds of miles when they leave hibernation sites in the spring.

“The National Park Service works with many other state and federal agencies of the White-nose Syndrome Response Team to learn more about the fatal disease and how to slow its spread,” said Michelle Verant, a Park Service wildlife Veterinarian and WNS expert. “Because of these proactive efforts to look for Pd, we are better positioned to respond and protect valuable bat populations.”

The Park Service is asking the public for help in stopping the spread of this disease. The best way you can help protect bats is by staying out of caves and areas that are closed. If you see a dead or sick bat, notify park rangers or state biologists. Do not handle bats. Additionally, you can help slow the spread of WNS by decontaminating your caving and hiking gear and boots. Do not reuse gear that has been used in WNS-affected areas. Visit https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/ for more information.

Public and private partnerships are also ready to respond with funding for innovative disease treatments through the Bats for the Future Fund. Response actions include a growing number of options available or under development, such as enhanced decontamination procedures, bat habitat modification, biocontrol of Pd, UV light to kill Pd, and a vaccine for bats

For more information about WNS, see https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/ For information about WNS response in the National Park Service, see https://www.nps.gov/subjects/bats/white-nose-syndrome.htm.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places