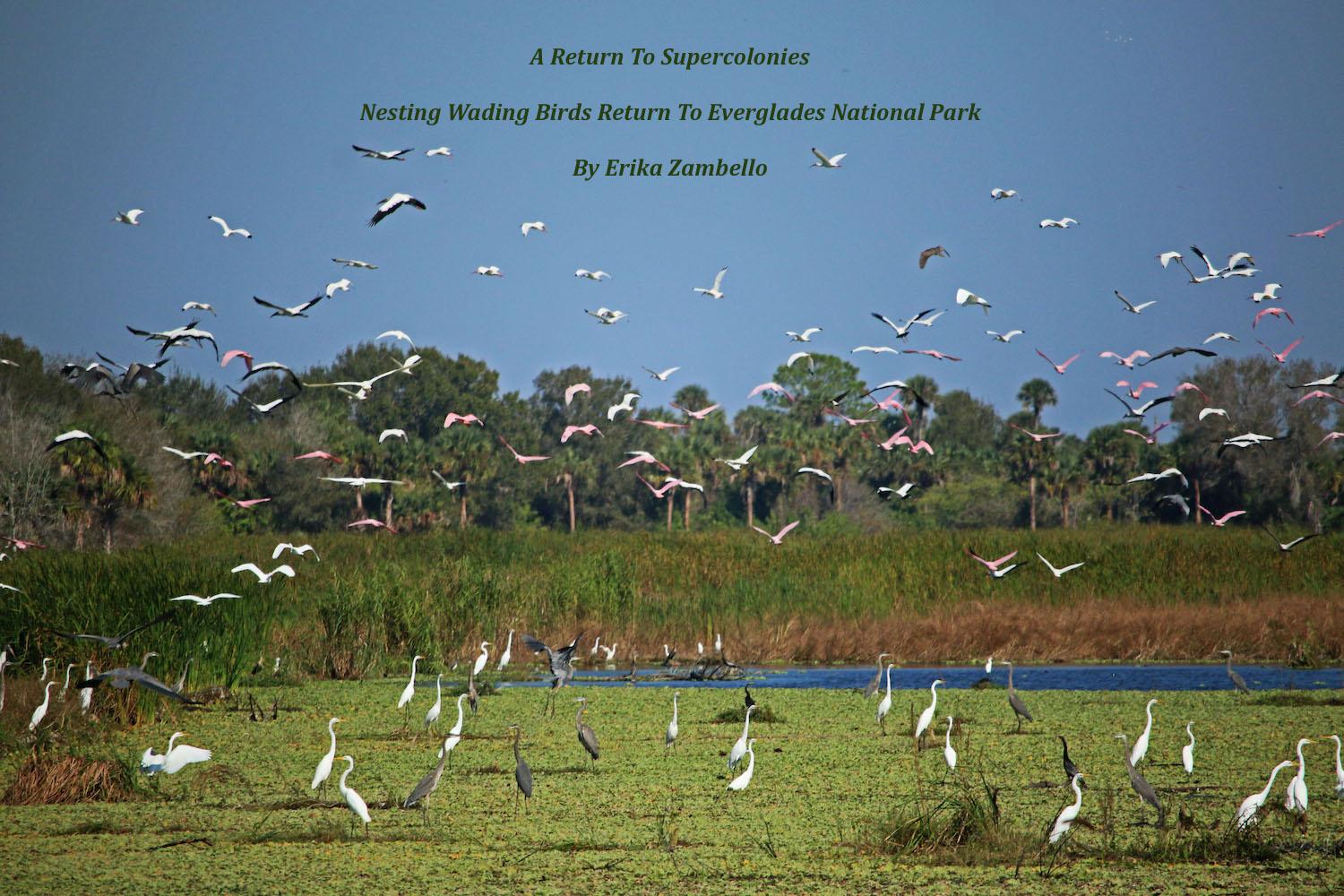

Flights of colorful birds fill the air in Everglades National Park during the nesting season. This past season brought the largest number of birds in years to the park for nesting, and hopefully is a harbinger for future nesting seasons / Erika Zambello

Swirling clouds of blue, white, and pink once rose above the Everglades in drifts that practically stained the sky when herons, egrets, storks, ibises, and spoonbills that numbered in the hundreds of thousands nested in the River of Grass. They took to the sky in giant, whirling clouds of feathers, intent on providing their chicks with enough food to fledge.

Adapted to the historic water conditions in South Florida, the mind-boggling nesting seasons of these birds first faced decimation by humans during the hat-plume craze at the turn of the 20th century, and then by the massive draining and reshaping of the Everglades after World War II.

By 2016, the numbers looked particularly bleak. According to the South Florida Water Management District’s annual wading bird report, nest counts had plummeted to their lowest numbers since 2008. Of the monitored species, White Ibises, Wood Storks, Snowy Egrets, Little Blue Herons, Tricolored Herons, and Great Egrets all experienced plunges in nesting levels, some over 50 percent. Only Roseate Spoonbills had increased nesting success, and only in inland regions. Birders and environmentalists began to despair; was the Everglades too far gone for restoration?

Then, the summer of 2017 rolled around. In a public workshop panel centered on the Everglades wading birds, Dr. Mark Cook of the water management district summarized that “a ‘perfect storm’ of ideal climatic conditions caused [a] super-colony event.” The birds had surged and made the 2018 nesting season one of the most prodigious in decades.

Wood storks turn trees into multi-story nesting units / Mark Cook

But let’s back up. Before the human-caused destruction of Everglades’ plumbing, years of poor nesting seasons contrasted with fantastic successes, according to normal fluctuations in annual weather and climate conditions. One year’s amazing nests would make up for the failure of another. However, as Everglades author Michael Grunwald described in his 2006 book, The Swamp, with the ambitious but ill-conceived Central and Southern Florida Project “[m]ore than 90 percent of [Everglades] wading birds and alligators had vanished” by the end of the 20th century. Not enough water flowed to the River of Grass.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, nesting of four wading bird indicator species (Snowy Egrets, White Ibises, Great Egrets, Wood Storks) averaged less than 8,500 nests total. After decades of fixes that yielded few results, Congress adopted the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan in 2000 to return the “right quality, timing, and distribution of water to the area.” Since then, nesting has picked up, with an average of almost 31,000 nests total from 2000 to 2017. As an example, in 2009 researchers counted more than 63,000 nests. Still, since 2011 nesting had been at, or below, this mean, with 2016 a particularly bad dip.

It’s no surprise then that in 2018 Dr. Cook says he “almost literally fell off my chair when I came to the final count of 112,000 nests.”

That would be 112,073, to be exact, close to the nesting levels prior to dredging and diking in the region. A total of 91,656 nests came from White Ibises, 14,130 from Great Egrets (the highest number ever counted), 2,769 from Snowy Egrets, and 3,518 from Wood Storks.

What happened?

While restoration efforts certainly helped, the weather conditions in 2017 that proved to be devastating to Puerto Rico and the Florida Keys provided a critical water pulse for the Everglades wading birds. From the air, Lori Oberhofer, a wildlife biologist at Everglades National Park, saw colonies so dense the birds appeared to coat the landscape like snow. Walking through the nesting areas themselves would showcase squawking young, the air alive with parents returning to their chicks

and then leaving again in search of food. Nests were clustered in close proximity to one another, many species sticking together in dense clusters, but often multiple wading varieties forming colonies together.

In short, the second half of 2017 proved to be wet. That moisture that arrived after a dry April and May of 2017 helped increase crayfish populations. Then, what the National Audubon Society described as “biblical downpours,” in the summer kicked off bands of precipitation, culminating in Hurricane Irma in September and peak water levels in October.

Along with nourishing vegetation, the moisture that fall and into 2018 pooled in the sloughs and estuaries before nesting season actually began. And that, for hungry adults and chicks, created an additional bird food explosion.

During nesting season, a gradual drydown of the water concentrated fish, crayfish, and other prey into small, easy-to- hunt pockets, allowing parents to bring food back to hungry young with ease. Wading bird chicks such as Roseate Spoonbills are intense feeders, explains Dr. Jerome Lorenz, state research director for Audubon Florida. The baby birds grow from their hatchling size close to a chicken egg all the way to nearly adult dimensions in only eight weeks. With the typical Roseate Spoonbill nest holding three eggs, that’s a lot of caloric needs for the avian family. When food is scarce, parent birds must spend too much time foraging, and not enough food reaches their chicks.

The final boon to nesting in 2018 came as spring turned to summer, when no huge rainstorms in April or May hit the region to cause water reversals, thereby avoiding the negative impacts of dispersing food sources. Those three weather patterns: a wet summer and fall, a gradual dry-down period, and a drier spring, created the happy proliferation of nests.

Wading birds act as critical indicator species for the Everglades region as a whole. Their strong nesting numbers in 2017-2018 provide evidence that both the bird species and the Everglades itself continue to harbor resilience.

A mix of wood storks, white ibis, and egrets made their nests along the Broad River on the gulf side of Everglades / NPS

Dr. Lorenz specifically addresses the important question: “Does [nesting success] mean we have succeeded in restoring the Everglades?”

“Not yet,” he concludes. “Mother Nature was really good to us this year.”

Dr. Lorenz did go on to say that restoration and management changes have helped. The water management district and other agencies try to give water to the conservation areas when possible, and additional projects are continually going from the design stage into the ground.

For example, in nearby Picayune Strand raised roads and canals are evened out to restore natural water flows to more than 50,000 acres. In the future, planners hope, among other things, to build water storage areas south of Lake Okeechobee to prevent large water discharges to the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuary ecosystems, remove levees and parts of the Miami Canal to increase both water sheetflow and freshwater flows to wetland areas. Overall, 18,000 square miles will be affected by restoration activities.

As restoration continues, park staff, locals, and wildlife lovers alike hope that the 2018 nesting success becomes the new normal, and that the scenes Alexander Sprunt, Jr. described in 1942—“as if humanity ceased to exist, and that we were intruders in a world which was people entirely by birds”—return for good.

Comments

Looks Good