An intended half-mile-long hike to Spruce Tree House, a well-preserved dwelling carved into a sandstone cliff face at Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado, ended in tragedy for Mitchell Dale Stehling, 51, and his family in the summer 2013.

“We know he is dead,” but his body has never been found, says his wife, Denean.

The trail to the 130-room archaeological site with eight ceremonial chambers, known as kivas, was closed in 2015 due to the possibility of rockfalls from the dwelling’s ceiling. But when the Stehling family left their Texas home to make a swing of some national parks and reached Mesa Verde in June 2013, the trail was self-guided and considered the “easiest” in the park.

Located on the Colorado Plateau in the high desert at elevation ranging from 7,000 to 8,500 feet, Mesa Verde includes some of the best archaeological wonders in the world and provides a glimpse into the Ancestral Pueblo people who lived there. Set atop a series of long, narrow mesas, the national park features rugged terrain with steep cliff and canyon overlooks and crumbling sandstone. Those who made the area home from 600 to 1300 CE were adept at traveling the landscape, and in places had cut toe- and handholds to scale cliffs to reach their dwellings. Due to its many archaeological wonders, today’s visitors to the park are extremely limited in where they can wander; in some places there are hidden cameras to alert staff when someone heads into the backcountry.

Denean speculates her “directionally challenged” husband, hiking without water or a map on a hot and sunny June day, might have been misled by a sign pointing to the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum and inadvertently went off trail.

A family spotted him on the nearby Petroglyph Point Trail. This 2.4-mile long, narrow, and rocky path requires hikers to clamber in places up a stone staircase to reach the top. There are places along the trail where it wouldn’t be hard for someone to wander into the backcountry. The family told Stehling’s wife they leapfrogged past one another and were together at the petroglyph panel 1.4 miles from the trailhead, but they never saw him afterwards. Neither did anyone else, though later there were reports from a hiker on the Petroglyph Point Trail who claimed to have heard someone calling for help

“He could have fallen off into Navajo Canyon,” says Denean, noting there are several steep drop-offs atop the canyon wall. Landslides and rockfalls are part of the park’s history, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

A drone the National Park Service sent into the area to look did not shed light on his whereabouts.

Stehling is one of at least 60 unresolved missing person cases in the National Park System, according to data obtained from the Park Service. The exact number is not publicly available, but could be hundreds or more. Most search-and-rescue missions end quickly with the subject(s) found, but others remain frustratingly unresolved. With landscapes ranging from above-timberline alpine settings and dense forests cut by canyons to desertscapes and oceans, the National Park System can be a surprisingly easy place to go, and stay, missing.

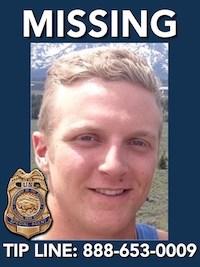

In 1969, 7-year-old Dennis Martin went missing at Great Smoky Mountains National Park during a family campout on Father’s Day Weekend. Eight-year-old Samuel Boehlke went missing in Crater Lake National Park in October 2006 and never was found. Joshua Tree National Park in California frequently is the backdrop for missing hikers. A Canadian man hasn’t been seen since going for a hike there this past July, and Bill Ewasko, a 65-year-old from Georgia, went missing in June 2010. Morgan Heimer, a Cody, Wyoming, man working as a river guide in Grand Canyon National Park, vanished during a group hike on June 2, 2015.

Just last month, after a month of searching, the mission to find a New Jersey man who vanished in the rugged backcountry of Rocky Mountain National Park was suspended as heavy snows of winter arrived. Once spring’s warmth melts the snow and ice the search is expected to resume, but it will be a recovery, not rescue, mission then.

And there are many other cases that fill books, such as Lost! by Dwight McCarter and Ronald Schmidt and Death, Daring, & Disaster By Charles “Butch” Farabee, Jr.

While law enforcement agencies at the Interior Department now record missing persons in the Incident Management and Reporting System, this practice only began in 2013. Missing person information is also entered into the National Law Enforcement Telecommunications System – an information-sharing network available to state, local, and federal law enforcement agencies and organizations. Individual park units also may notify local authorities when someone cannot be found.

There is no comprehensive roster of all persons who have gone missing across the National Park System. Part of the reason is that the Park Service might not be the lead agency in looking for someone reported missing. County sheriff’s departments and even authorities from local municipalities might assume control of the investigations, with information sometimes flowing back to the park in question. The Park Service does, however, record cumulative figures submitted and compiled from its regional offices, says Travis Heggie, a former public risk management specialist and tort claims officer for the Park Service. Now an associate professor at Bowling Green State University, Heggie says individual parks keep the original search-and-rescue reports.

At Yosemite National Park, there are more than 30 missing persons dating back to 1909, when F.P. Shepherd got lost on the way to Sentinel Dome offering views of Yosemite Falls and Half Dome. A new case added this year is that of Maximillian “Max” Lee Schweitzer, whose rented vehicle was discovered January 5 at parking for Camp 4 in Yosemite Valley not far from Yosemite Valley Lodge after the rental company reported the car overdue. A Linked-In profile says he is a clandestine analyst in the Office of Intelligence and Analysis at the Department of Homeland Security. Yosemite National Park posts Facebook and Twitter messages encouraging anyone knowing anything about Schweitzer to contact the Park Service.

Former park ranger Andrea Lankford believes that in time social media will play a greater role in finding missing persons.

“I anticipate the Park Service having a high-profile case at some point,” she said in a call from her California home. “Because of social media, thousands of people can read about the case, get engaged and help.”

On its website, the Park Service’s Investigative Services lists 12 “cold cases” at Yosemite; these are unsolved matters with no active leads, such as the case of Stacey Anne Arras, who disappeared to take photographs on July 17, 1981, after leaving her father and others camped at Sunrise High Sierra Camp. The father and daughter were part of a group of 10 people riding mules on the High Sierra Loop at Tuolumne Meadows, the largest high-elevation meadows in the Sierra Nevada at 8,600 feet. Approximately 100 people, as well as helicopters and dog teams, searched fruitlessly for the 14-year-old girl on several occasions.

Also never found was Peter Jackson, who arrived at Yosemite’s rocky White Wolf Campground at 8,000 feet about September 17, 2016, and paid for his site through September 21, 2016. The 74-year-old man is believed to have gone on a day hike.

Yosemite is not alone with its missing persons list. People young and old have gone missing from parks across the country; the stories are material for reality television programs, like Rescue 911. Indeed, an episode of the X-Files covered the case of Joseph and William Whitehead, whose disappearance in Glacier National Park in Montana during the summer 1924 brought in the FBI’s involvement, says Lankford, whose career provided the fodder for her book, Ranger Confidential: Living, Working, and Dying in the National Parks.

Then there’s the case of Paul Fugate, a park ranger at Chiricachua National Monument in southeastern Arizona. Known for its rhyolite rock pinnacles balancing on small bases that look as if they could easily topple, the remote park spreads across more than 12,000 acres, featuring shallow caves, canyons, faults, ancient lava flows, and a giant volcanic caldera.

At about 2 p.m. on January 13, 1980, Fugate went for a hike wearing his green and grey Park Service uniform. He was never seen again. Investigators suspected foul play. Some people, including his wife, Dody, speculated that he stumbled on a drug deal and was abducted. The case was classified as “cold,” but this year unspecified information renewed investigators’ interest in solving this 38-year-old mystery. The Park Service increased to $60,000 the reward for information leading to his whereabouts and/or the arrest and conviction of whoever was responsible for his disappearance.

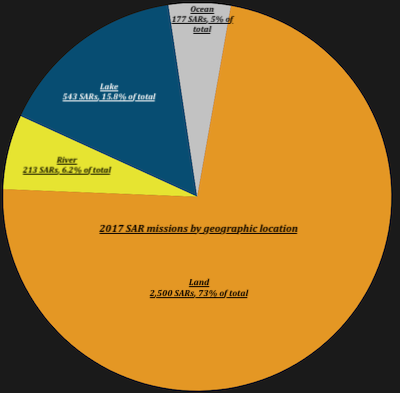

The Park Service’s most recent search-and-rescue database, the 2017 Annual SAR Dashboard, sheds some light on rescue operations across all park units in the more than 84-million-acre park system. In 2017, there were 3,453 reported search and rescue missions, including 1,000 saves; rescues of 1,500 ill or injured people, and 182 fatalities.

Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada with 563 incidents recorded had the greatest number of SAR operations system-wide in 2017. Along with two vast lakes – Mead and Mohave – covering more than 29 squares miles of waterway open to boating, fishing, houseboats, kayaking, canoeing, swimming and water skiing, the 1.5-million-acre park lures mountain bikers, backpackers, and hikers into its mountains and canyons.

Since 2010, four people were reported missing at Lake Mead, including Brian Yule last seen this past August 11. A game warden with the Nevada Department of Wildlife found the 69-year-old man’s 25-foot-long sailing vessel on Lake Mead, but not Yule. Another missing person, Bill Guruley, was last seen November 9, 2010. The 58-year-old is believed to have fallen from a canoe in a Colorado River rapid near Pearce Ferry that day. He was not wearing a life jacket and reportedly was not a good swimmer, either.

In second place for the most number of SAR incidents in 2017 was Grand Canyon National Park, with 290 SAR incidents. Then came Yosemite, 233; Rocky Mountain, 165; Sequoia and Kings Canyon, 138; Zion, 114; Great Smoky Mountains, 100, and; Bryce Canyon, 86.

A number of park units, including Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southern Arizona’s Sonoran Desert, New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park in Louisiana, and Richmond National Battlefield Park in Virginia, had no SAR operations in 2017.

Last year the Park Service spent $3.1 million on SAR operations, plus an additional $314,000 on supplies and other SAR costs – an average of $985 per incident. In general, the agency does not charge those needing to be rescued for these efforts.

The SAR dashboard reveals some interesting trivia. For instance, in 2017, men were rescued 1,800 times compared to 1,300 SAR operations for women; in 549 cases, the person’s sex was not reported. Almost 20 percent of the rescues involved people between the age of 20-29, and 16 percent of the rescues were people over age 60.

The majority of rescue operations -- 2,500 -- were on land, vs. 543 on a lake, 213 on a river, and 177 in the ocean.

As operations chief in charge of the search for a missing 22-year-old man at Grand Canyon National Park in 1995, Lankford recalls the importance of involving families in search operations, but also the difficulty she experienced when she told a father the search for his son, Gabriel Parker, was winding down. It’s incredibly tough to tell someone the search for his or her loved one is over and unresolved, Lankford explained.

“I have cried about this case,” she says, noting that the man’s body was found eight months after the search began at the base of the Redwall Cavern, a giant amphitheater created by the river eroding away from the limestone Grand Canyon walls. It is not clear if his death was by suicide or a fall, says Lankford.

Retired police officer David Paulides criticizes the Park Service for not making the comprehensive list of missing persons available to the public, and has chided the agency for what he perceives as its indifference towards missing people in the parks.

“You can go into any police department in the United States and within an hour the police chief would lay down a list,” he says, but the Park Service will not release anything comprehensive.

In Paulides’ view, a complete list would be helpful to people seeking details from the government bureaucracy about missing family members, and would enable families to share information with others in a similar predicament. Additionally, a list could increase the public’s awareness of potential threats, such as avalanche, topographic issues making hiking in a particularly area dangerous, and parks where there may be “a rash of mission persons,” he says.

When Paulides used the Freedom of Information Act to try and obtain a list of unsolved cases, he was told it would cost him $1.4 million in fees. Even though he is the author of the book series, Missing 411, the Park Service said he did not qualify for a news media fee exemption because his books are not in enough libraries.

Heidi Streetman, an adjunct professor at Denver Community College, agrees with Paulides about the need for openness. She collected more than 10,000 signatures on a petition requesting a national database of persons missing on federal lands. She delivered the petition to the office of U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colorado), but has yet to hear if any action will be taken.

Meanwhile, Denean Stehling continues to press the Park Service to keep looking for her husband at Mesa Verde. She played a key role in getting the Colorado Forensic Canines, specializing in human remains detection, to search the trails on several occasions. She put up posters in the restrooms at Mesa Verde about her missing husband, only to find them removed the next day.

“We feel very jaded that the park has not done more. Everything that has been done has been a fight,” she says.

Park staff, though, are left wondering what more they could have done.

“We did a lot. I was out on a search party. We mounted an extensive two-week-long search. We had a helicopter here for at least a week,” said Tim Hovezak, Mesa Verde’s cultural resources program manager. “We worked really hard to find him."

Lori Sonken held senior staff positions working on natural resource policy in the U.S. Congress and Department of the Interior. Now at Cornell University, she hiked the John Muir Trail passing through Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia national parks during the summer 2018.

Comments

I lived on Ponepe in the Eastern Caroline Islands. I've heard several stories about people that have gone missing, suicides, that Have gone mad, seeing "ghosts" all centered around Nom Midol* log cabin stacking of basalt log built by "giants" not by the locals. In WWII the Japanese stayed out of the area. The allies never landed on this island to over take. The locals are deathly afraid of ghosts. To this day no one walks around certain trees at night. Don't play jokes on them that could scare them. They might go insane or die.

Very frightening and mysterious. Does anyone have an idea ...is there FBI jurisdiction here?

I don't mean to sound harsh, but among all the possible explanations to many of these disappearances, particularly those that seem absolutely incomprehensible, has nobody ever considered it's the parks guards who know best the place and circumstances, and are aware of groups and solo hikers? Linking this to the lack of cooperation and obscuantism of the responsible departments involved, this idea sounds to me far more sensible than U.F.O., Bigfoot, and other such theories.

I pray for closure and strength in your waiting

In the Fall of 1996, on the very last day for that year that Yellowstone National Park would be open to the public, my daughter and I had a one time chance to visit the park sights. I recall it was a beautiful day and we made the best of things in the time allowed us. At one point we sat on a big bolder taking pictures of ourselves with the sight of one most frequently photograped YSP waterfall in the background.

There were very few people we encountered during our visit, so when during our photo shot break time, it was obvious when a man walked up to stand near us and observe the falls with us. He stood just to the right of the bolder and closer to the view of the falls. Being I was visiting my college age daughter for just 2 days we spent our time enjoying the natural beauty of the park while also catching up on things. wed just come thru our first big separation. It was when we prepared to leave, we suddenly realized we never saw the man depart, and he would have needed to pass in front of us to leave the area. I recall we questioned what could happened to him. We even looked about to see if he'd taken some path or something. There were no paths, trails or possible other routes out due to a very sheer drop off that led to the river. We even strained to see if we could see anything down below, but nothing was visible, no were there skid marks that he might have slid ad fallen, nor had we heard anything. It was as if he just disappeared. We figured we must have just missed seeing him depart during our conversation with each other and enjoying the view.

back in the car, we decided we would tell the park rangers before leaving the park. Then a short distance down the road while making our way back to the park exit gate before closing at dusk our rental car suddenly became totally surrounded by a very large herd of bison. The huge animals were literally on all four sides of us, even pressing against the car. We could move no faster than the huge animals crept along as the afternoon sky was losing sunlight. The time restraints and scary experience with the bison weighed on us so we did not think of trying to locate a ranger to report the situation with that man after passing thru the exit gate and there being no rangers about. Unfortunately I had to leave my daughter at her dorm room in Rexburg and head several hours back to Salt Lake City that same night for some job training That would begin the next morning.

it may seem odd to readers that I would report this all now, but they are details i had not thought of for years until recently hearing reports about the many missing people in our national parks. My hopes are that should someone have been searching for a missing man in Yellowstone during that time frame, hopefully this might provide some answers. Sadly we can no longer recall enough of what this man looked like to provide a description of him, other than to believe he appeared to be in his 20s or 30s. I want to believe he was think, about 5'9" and wearing a hat.

hello,

Don't understand why you are calling David Paulides a "kook"? HE is the one who is bringing light to this subject. He has not ONCE given a theory as to what it is.......in the books.

I don't think BF is responsible for ALL of these instances, but it can be related to a few thru eyewitness testimony. Just because you don't believe in BF, doesn't mean it doesn't exist.

Good luck to you,

and people, DO NOT GO INTO THE WILDERNESS ALONE, EVER!!

Not a bad idea to propose it to them! Be a great project if they actually accepted that kind of offer.

However, based on what I have read, including the comments of the loved ones of persons reported missing, and the efforts of researchers such as David Paulides, I am inclined to think that the reason for the lack of a public database and the obvious resistance to creating one, is not just apathy or laziness or lack of technical ability; but primarily political. The brass simply doesn't want the negative press and the damage to the reputation of the NPS that could result if these incidents featured more prominently in the public consciousness because it would cause fear and would result in a decline of visitors and revenues, which could threaten the entire bureaucracy. Like a black eye for management, because it would also open them up to criticism ("Why aren't you doing a better job at ensuring the safety of park visitors, Mr. Superintendent of the Park Service?") Who wants that kind of scrutiny and liability? That's the kind of thing that can end careers. So there's that political/self-preservation dynamic operating...and despite the fact that the NPS is funded with many sources including substantial federal funding from Congressional appropriations, I can appreciate that the fees and the concessions and all of that kind of thing must be a significant portion and probably looked on as a metric of management success.

As an aspiring park adventurer (I have visited many Western parks during my life, but it is my dream and goal to visit ALL of the parks in the system after retirement), I have to say I'm of two minds on this. On the one hand, I really like the idea of full transparency...a complete view into every serious incident involving serious injury, loss of life, or disappearance reported in the system. I believe that it is usually not possible to have too much information and I think because the public pays for these parks, we deserve to have that information. And on the other hand, I appreciate that these spaces are wilderness and inherently they are dangerous. Even in the modern era, and perhaps especially in the modern era, there are few places so bereft of human presence as the further reaches of national parks. Heck, even in State or County parks it is possible to go to places where you will not see another human the entire time you are there...and that means that when it comes to safety, and security, you're on your own. It is just you and Nature and all of its predators, including the most dangerous ones (other humans).

But I think if nothing else, knowing the full extent of the actual hazards that have occurred in parks allows visitors to take them as seriously as they should. Personally I don't need the information in order to be cautious - I really just need it to be better informed as to the nature of the risks. I've always been a cautious person, and I never hike the backcountry without survival items: GPS, water, first aid kit, whistle, emergency shelter, fire tool, and a weapon. If I am in a wilderness area, that includes not just weapons useful against humans but against animals as well (bear spray). Despite taking these precautions, which others have deemed paranoid (or which may even be prohibited in that place), there is still a possibility of accidental injury and death...which is why in addition to carrying a first aid kit I have practiced self-rescue techniques. Of course, there are many situations imaginable in which neither weapons nor first aid kits will be of any use, and I have to believe that of these certainly inexplicable disappearances, many or possibly most, are simply due to unfortunate accidents and natural causes, and not to foul play, malice or animal predation. But some of those situations, such as getting lost and dying due to exposure, are preventable or avoidable.

That being said, you can't be too prepared, or too informed....so its good to try to be both. Some find this a chore...but I find it very relaxing. Knowing that I have done all that I could have to be prepared and safe....brings me tranquility and peace of mind and allows me to focus simply on enjoying my experiences rather than worrying about what might happen. IF something happens, I will deal with it the way I have been trained to and have prepared for. And that's all I can really do. If I still wind up dead or injured despite all of that effort, well, c'est la vie. You can't avoid EVERY risk that exists in the world. You have to live your Life too.

Yes, I also don't understand the vitriol here. I don't think he is a kook. He could be eccentric, but I don't think he's insane or anything. Remember, he was a police officer. They pass a mental health screening, they are trained observers, they are taught to be analytical (or they are analytical people before ever being trained as cops). I know cops are just people, most are certainly just normal average people, but the point is, I think his interest in the unknown is certainly in line with the training and personality of a good police officer. Whether he has less or more credulousness than the average person is hard to say as well. Look at what percentages of Americans harbor supernatural beliefs, or subscribe to religious dogma that is far more incredible than a theory that a previously unknown species exists (as a matter of fact unknown species continue to be discovered at a fairly regular rate).

I have read only one of his 411 books, but nothing in the books would lead me to question his sanity or mental stability.

I took a little road trip recently down to Santa Barbara, and on the trip we passed not one, not two, but THREE "Psychic Reader" businesses. I have to be honest here, I feel that a sincere, well-researched belief in the existence of a Sasquatch-like creature is more defensible and reasonable than belief in psychics or astrology, or homeopathy (the latter two of which are proven outright frauds with no scientific basis).