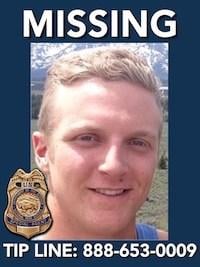

An intended half-mile-long hike to Spruce Tree House, a well-preserved dwelling carved into a sandstone cliff face at Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado, ended in tragedy for Mitchell Dale Stehling, 51, and his family in the summer 2013.

“We know he is dead,” but his body has never been found, says his wife, Denean.

The trail to the 130-room archaeological site with eight ceremonial chambers, known as kivas, was closed in 2015 due to the possibility of rockfalls from the dwelling’s ceiling. But when the Stehling family left their Texas home to make a swing of some national parks and reached Mesa Verde in June 2013, the trail was self-guided and considered the “easiest” in the park.

Located on the Colorado Plateau in the high desert at elevation ranging from 7,000 to 8,500 feet, Mesa Verde includes some of the best archaeological wonders in the world and provides a glimpse into the Ancestral Pueblo people who lived there. Set atop a series of long, narrow mesas, the national park features rugged terrain with steep cliff and canyon overlooks and crumbling sandstone. Those who made the area home from 600 to 1300 CE were adept at traveling the landscape, and in places had cut toe- and handholds to scale cliffs to reach their dwellings. Due to its many archaeological wonders, today’s visitors to the park are extremely limited in where they can wander; in some places there are hidden cameras to alert staff when someone heads into the backcountry.

Denean speculates her “directionally challenged” husband, hiking without water or a map on a hot and sunny June day, might have been misled by a sign pointing to the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum and inadvertently went off trail.

A family spotted him on the nearby Petroglyph Point Trail. This 2.4-mile long, narrow, and rocky path requires hikers to clamber in places up a stone staircase to reach the top. There are places along the trail where it wouldn’t be hard for someone to wander into the backcountry. The family told Stehling’s wife they leapfrogged past one another and were together at the petroglyph panel 1.4 miles from the trailhead, but they never saw him afterwards. Neither did anyone else, though later there were reports from a hiker on the Petroglyph Point Trail who claimed to have heard someone calling for help

“He could have fallen off into Navajo Canyon,” says Denean, noting there are several steep drop-offs atop the canyon wall. Landslides and rockfalls are part of the park’s history, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

A drone the National Park Service sent into the area to look did not shed light on his whereabouts.

Stehling is one of at least 60 unresolved missing person cases in the National Park System, according to data obtained from the Park Service. The exact number is not publicly available, but could be hundreds or more. Most search-and-rescue missions end quickly with the subject(s) found, but others remain frustratingly unresolved. With landscapes ranging from above-timberline alpine settings and dense forests cut by canyons to desertscapes and oceans, the National Park System can be a surprisingly easy place to go, and stay, missing.

In 1969, 7-year-old Dennis Martin went missing at Great Smoky Mountains National Park during a family campout on Father’s Day Weekend. Eight-year-old Samuel Boehlke went missing in Crater Lake National Park in October 2006 and never was found. Joshua Tree National Park in California frequently is the backdrop for missing hikers. A Canadian man hasn’t been seen since going for a hike there this past July, and Bill Ewasko, a 65-year-old from Georgia, went missing in June 2010. Morgan Heimer, a Cody, Wyoming, man working as a river guide in Grand Canyon National Park, vanished during a group hike on June 2, 2015.

Just last month, after a month of searching, the mission to find a New Jersey man who vanished in the rugged backcountry of Rocky Mountain National Park was suspended as heavy snows of winter arrived. Once spring’s warmth melts the snow and ice the search is expected to resume, but it will be a recovery, not rescue, mission then.

And there are many other cases that fill books, such as Lost! by Dwight McCarter and Ronald Schmidt and Death, Daring, & Disaster By Charles “Butch” Farabee, Jr.

While law enforcement agencies at the Interior Department now record missing persons in the Incident Management and Reporting System, this practice only began in 2013. Missing person information is also entered into the National Law Enforcement Telecommunications System – an information-sharing network available to state, local, and federal law enforcement agencies and organizations. Individual park units also may notify local authorities when someone cannot be found.

There is no comprehensive roster of all persons who have gone missing across the National Park System. Part of the reason is that the Park Service might not be the lead agency in looking for someone reported missing. County sheriff’s departments and even authorities from local municipalities might assume control of the investigations, with information sometimes flowing back to the park in question. The Park Service does, however, record cumulative figures submitted and compiled from its regional offices, says Travis Heggie, a former public risk management specialist and tort claims officer for the Park Service. Now an associate professor at Bowling Green State University, Heggie says individual parks keep the original search-and-rescue reports.

At Yosemite National Park, there are more than 30 missing persons dating back to 1909, when F.P. Shepherd got lost on the way to Sentinel Dome offering views of Yosemite Falls and Half Dome. A new case added this year is that of Maximillian “Max” Lee Schweitzer, whose rented vehicle was discovered January 5 at parking for Camp 4 in Yosemite Valley not far from Yosemite Valley Lodge after the rental company reported the car overdue. A Linked-In profile says he is a clandestine analyst in the Office of Intelligence and Analysis at the Department of Homeland Security. Yosemite National Park posts Facebook and Twitter messages encouraging anyone knowing anything about Schweitzer to contact the Park Service.

Former park ranger Andrea Lankford believes that in time social media will play a greater role in finding missing persons.

“I anticipate the Park Service having a high-profile case at some point,” she said in a call from her California home. “Because of social media, thousands of people can read about the case, get engaged and help.”

On its website, the Park Service’s Investigative Services lists 12 “cold cases” at Yosemite; these are unsolved matters with no active leads, such as the case of Stacey Anne Arras, who disappeared to take photographs on July 17, 1981, after leaving her father and others camped at Sunrise High Sierra Camp. The father and daughter were part of a group of 10 people riding mules on the High Sierra Loop at Tuolumne Meadows, the largest high-elevation meadows in the Sierra Nevada at 8,600 feet. Approximately 100 people, as well as helicopters and dog teams, searched fruitlessly for the 14-year-old girl on several occasions.

Also never found was Peter Jackson, who arrived at Yosemite’s rocky White Wolf Campground at 8,000 feet about September 17, 2016, and paid for his site through September 21, 2016. The 74-year-old man is believed to have gone on a day hike.

Yosemite is not alone with its missing persons list. People young and old have gone missing from parks across the country; the stories are material for reality television programs, like Rescue 911. Indeed, an episode of the X-Files covered the case of Joseph and William Whitehead, whose disappearance in Glacier National Park in Montana during the summer 1924 brought in the FBI’s involvement, says Lankford, whose career provided the fodder for her book, Ranger Confidential: Living, Working, and Dying in the National Parks.

Then there’s the case of Paul Fugate, a park ranger at Chiricachua National Monument in southeastern Arizona. Known for its rhyolite rock pinnacles balancing on small bases that look as if they could easily topple, the remote park spreads across more than 12,000 acres, featuring shallow caves, canyons, faults, ancient lava flows, and a giant volcanic caldera.

At about 2 p.m. on January 13, 1980, Fugate went for a hike wearing his green and grey Park Service uniform. He was never seen again. Investigators suspected foul play. Some people, including his wife, Dody, speculated that he stumbled on a drug deal and was abducted. The case was classified as “cold,” but this year unspecified information renewed investigators’ interest in solving this 38-year-old mystery. The Park Service increased to $60,000 the reward for information leading to his whereabouts and/or the arrest and conviction of whoever was responsible for his disappearance.

The Park Service’s most recent search-and-rescue database, the 2017 Annual SAR Dashboard, sheds some light on rescue operations across all park units in the more than 84-million-acre park system. In 2017, there were 3,453 reported search and rescue missions, including 1,000 saves; rescues of 1,500 ill or injured people, and 182 fatalities.

Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada with 563 incidents recorded had the greatest number of SAR operations system-wide in 2017. Along with two vast lakes – Mead and Mohave – covering more than 29 squares miles of waterway open to boating, fishing, houseboats, kayaking, canoeing, swimming and water skiing, the 1.5-million-acre park lures mountain bikers, backpackers, and hikers into its mountains and canyons.

Since 2010, four people were reported missing at Lake Mead, including Brian Yule last seen this past August 11. A game warden with the Nevada Department of Wildlife found the 69-year-old man’s 25-foot-long sailing vessel on Lake Mead, but not Yule. Another missing person, Bill Guruley, was last seen November 9, 2010. The 58-year-old is believed to have fallen from a canoe in a Colorado River rapid near Pearce Ferry that day. He was not wearing a life jacket and reportedly was not a good swimmer, either.

In second place for the most number of SAR incidents in 2017 was Grand Canyon National Park, with 290 SAR incidents. Then came Yosemite, 233; Rocky Mountain, 165; Sequoia and Kings Canyon, 138; Zion, 114; Great Smoky Mountains, 100, and; Bryce Canyon, 86.

A number of park units, including Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southern Arizona’s Sonoran Desert, New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park in Louisiana, and Richmond National Battlefield Park in Virginia, had no SAR operations in 2017.

Last year the Park Service spent $3.1 million on SAR operations, plus an additional $314,000 on supplies and other SAR costs – an average of $985 per incident. In general, the agency does not charge those needing to be rescued for these efforts.

The SAR dashboard reveals some interesting trivia. For instance, in 2017, men were rescued 1,800 times compared to 1,300 SAR operations for women; in 549 cases, the person’s sex was not reported. Almost 20 percent of the rescues involved people between the age of 20-29, and 16 percent of the rescues were people over age 60.

The majority of rescue operations -- 2,500 -- were on land, vs. 543 on a lake, 213 on a river, and 177 in the ocean.

As operations chief in charge of the search for a missing 22-year-old man at Grand Canyon National Park in 1995, Lankford recalls the importance of involving families in search operations, but also the difficulty she experienced when she told a father the search for his son, Gabriel Parker, was winding down. It’s incredibly tough to tell someone the search for his or her loved one is over and unresolved, Lankford explained.

“I have cried about this case,” she says, noting that the man’s body was found eight months after the search began at the base of the Redwall Cavern, a giant amphitheater created by the river eroding away from the limestone Grand Canyon walls. It is not clear if his death was by suicide or a fall, says Lankford.

Retired police officer David Paulides criticizes the Park Service for not making the comprehensive list of missing persons available to the public, and has chided the agency for what he perceives as its indifference towards missing people in the parks.

“You can go into any police department in the United States and within an hour the police chief would lay down a list,” he says, but the Park Service will not release anything comprehensive.

In Paulides’ view, a complete list would be helpful to people seeking details from the government bureaucracy about missing family members, and would enable families to share information with others in a similar predicament. Additionally, a list could increase the public’s awareness of potential threats, such as avalanche, topographic issues making hiking in a particularly area dangerous, and parks where there may be “a rash of mission persons,” he says.

When Paulides used the Freedom of Information Act to try and obtain a list of unsolved cases, he was told it would cost him $1.4 million in fees. Even though he is the author of the book series, Missing 411, the Park Service said he did not qualify for a news media fee exemption because his books are not in enough libraries.

Heidi Streetman, an adjunct professor at Denver Community College, agrees with Paulides about the need for openness. She collected more than 10,000 signatures on a petition requesting a national database of persons missing on federal lands. She delivered the petition to the office of U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colorado), but has yet to hear if any action will be taken.

Meanwhile, Denean Stehling continues to press the Park Service to keep looking for her husband at Mesa Verde. She played a key role in getting the Colorado Forensic Canines, specializing in human remains detection, to search the trails on several occasions. She put up posters in the restrooms at Mesa Verde about her missing husband, only to find them removed the next day.

“We feel very jaded that the park has not done more. Everything that has been done has been a fight,” she says.

Park staff, though, are left wondering what more they could have done.

“We did a lot. I was out on a search party. We mounted an extensive two-week-long search. We had a helicopter here for at least a week,” said Tim Hovezak, Mesa Verde’s cultural resources program manager. “We worked really hard to find him."

Lori Sonken held senior staff positions working on natural resource policy in the U.S. Congress and Department of the Interior. Now at Cornell University, she hiked the John Muir Trail passing through Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia national parks during the summer 2018.

Comments

I was watching missing 411 the odd part was I had not seen the episode with your brother's story. It came back to me in a flash about his story and the similarities to the other stories being told. So the latest update I read was they found his personal items but still have not found his body? It is hard enough losing a loved one but never finding remains would be devastating. I would think with all the technology they could look with drones? I hope you get some answers. I will keep you all in my prayers. I hope others will as well.

There is something in those parks also in canada 50 hikers have gone missing have you heard about the slendermans forest is now apart of a national park heh maybe Siren head or Cartoon cat probly they killed the hikers

There is definitely something sinister & strange going on with these national/state parks. To include woods, forests, & deserts. Too many people are either found missing, or deceased. Unexplained cause of death. How come thereare no listings available to the general public? It appears the government, FBI, & other associated agencies know a lot more than what they are willing to reveal!!! Ask yourself WHY???

In August 2021, a family & their dog were found dead on a trail inside Yosemite National Park. A husband, wife, their one year old little girl, & the family dog. Again, "unexplained cause of death!" What is going on here? Why are these incident so hush-hush? What is being covered up? The lost of revenue generated by those who camp, fish, hunt, or hike would be tremendous. Yet, there is more going on here than meets the eye!

Never happened.

There was a rather well-covered case of a family of three with an infant and dog that died in Sierra National Forest in August 2021, but that was outside of Yosemite National Park. And the latest report indicates that they died of heat stroke and possible dehydration. It was over 100 deg F that day and they started late in the day. Nothing really all that mysterious about those circumstances. And they were found 2 days later.

https://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article255157607.html

I have been a seasonal park ranger for the last eight summers at 4 different parks, including Yosemite, Rocky Mtn and Grand Teton. During those 8 summers I witnessed dozens of SARS. in every case the rescue Rangers worked themselves almost to exhaustion trying to find the missing persons. The problem is, you can make not so bright decisions in normal life and usually get away with it. In a wild National Park nature doesn't care about you when you make careless decisions, she will kill you without hesitation. We in the parks try to drive home this information, but most visitors ignore the advice, much to the detriment of some of them.

God be with you and your family, I'm so sorry for the loss of you're brother and how he just went missing may the lord be with you in these trying times in America.

Like it or not some of these people were likely taken prey by Cougar, Grizz or Black bear & devour'd...!

Mentioning David Paulides as a source in this article really strains its credibility, as he uses these cases to enrich his own pocketbook with sensationalist books, many which stretch the truth and even make up stuff. Here's part of a Wiki page about him, which also says: While working as a court liaison officer in December 1996, Paulides was charged with a misdemeanor count of falsely soliciting for a charity.

David Paulides is a former police officer who is now an investigator and writer known primarily for his self-published books dedicated to proving the reality of Bigfoot, and establishing the Missing 411conspiracy. Missing 411 is a series of books and a film, which document cases of people who have gone missing in national parks and elsewhere, and maintain that these cases are unusual and mysterious, contrary to data analysis which suggests that they are not actually statistically mysterious or even unexpected.

Kyle Polich, a data scientist and host of the Data Skeptic podcast, documented his analysis of Paulides' claims in the article "Missing411" and presented his analysis to a SkeptiCamp held in 2017 by the Monterey County Skeptics. He concluded that the allegedly unusual disappearances represent nothing unusual at all, and are instead best explained by non-mysterious causes such as falling or sudden health crises leading to a lone person becoming immobilized off-trail, drowning, bear (or other animal) attack, environmental exposure, or even deliberate disappearance. After analyzing the missing person data, Polich concluded that these cases are not "outside the frequency that one would expect, or that there is anything unexplainable that I was able to identify." This presentation was discussed in a February 2017 article in Skeptical Inquirer, a publication of the CSI. In the article, Susan Gerbic reported "Paulides... gave no reason for these disappearances but finds odd correlations for them. For example, two women missing in different years both had names starting with an 'A' with three-letters, Amy and Ann." Polich concluded in his analysis: "I've exhausted my exploration for anything genuinely unusual. After careful review, to me, not a single case stands out nor do the frequencies involved seem outside of expectations."