Understanding the historian's role in the National Park System/Buddy Secor

Editor's note: Interpreting history is a key role of the National Park Service. In the following column, former NPS historian Harry A. Butowsky outlines the role of historians in the agency.

The National Park Service takes care of and interprets some of the most powerful and instructive historical places in the nation. Millions of Americans cultivate a deeper appreciation of the nation’s past through encounters with historic buildings and places. A thorough knowledge of our own history is essential in the making of Americans. The study and understanding of American history is important to the preservation of our democracy.

The National Park Service preserves sites of national significance in the evolution of the history of the United States. Our parks represent the key turning points in our history. They help us to understand ourselves as a people and nation in today’s complex world.

The Park Service historian is the keeper of the essence of American history. Unlike the academic historian who spends his life in the classroom and has never worked in government or business and spends his time in lectures and reading history to classes of undergraduate students, the Park Service historian meets the American people every day. Their audience is the nation. They are the ultimate student of history. They read all of the significant literature pertaining to their subject, and also walk the ground where it occurred. In many cases, they also interview the key people who have taken park in the history of their site.

The Park Service historian is not only a teacher and interpreter, but also the best subject matter specialist on the history of his park.

As individuals, communities, and countries, we are nothing without the fabric of history. History gives meaning to the stories of our lives. It provides the fabric upon when we can all stand to assess the present and hope for the future.

The National Park Service preserves this function for the nation.

The National Park Service preserves the key turning points in American history. At Independence National Historical Park, visitors learned how the 13 colonies changed and evolved into an independent nation based on the principles written in the Declaration of Independence. The park visitor also learns how only a few years later the newly independent states came together again to write the U.S. Constitution and created the most successful document for government in human history.

At Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, the visitor learns how America finally came together with the promise of equality embodied in the Declaration and the Constitution and outlawed the practice of segregation forever. Brown v. Board represents the fulfillment of the ideas of the Declaration and the Constitution and the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments of the Constitution.

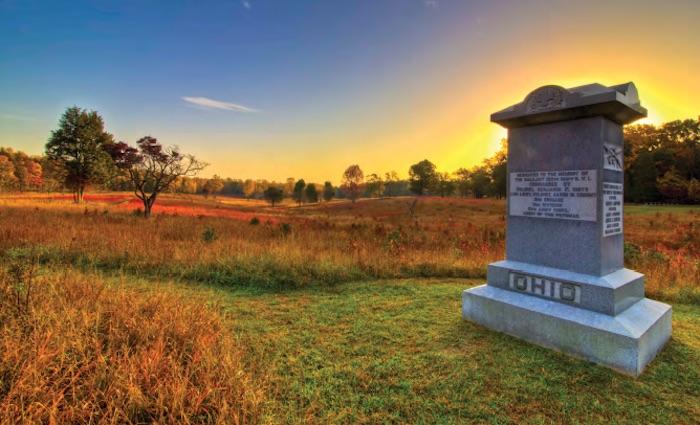

Similar lessons are learned from out many other parks. From Fort Sumter to Antietam, Vicksburg, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Petersburg and finally Appomattox, the visitor learns how America fought a terrible Civil War to preserve the unity of the nation. They learn how more than 600,000 Americans died in this struggle and why it is important today.

From Lowell National Historical Park, Americans learn of the early path of the nation to becoming the industrial power that is the marvel of the world today. From Pullman National Monument they learn of the price American workers paid in the evolution of the Industrial Revolution.

From the homes of the many presidents and other prominent Americans preserved, they learn the importance of these men and women who guided the nation throughout its history. Walking the grounds of Franklin D. Roosevelt's home at Hyde Park in New York, the Eisenhower National Historic Site, or the Harry S Truman National Historic Site gives a new dimension to understanding these prominent Americans.

Visiting the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal teaches Americans of the first movement of the colonies to the west. Other parks, such as Arkansas Post National Memorial Site, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Gateway Arch National Park (aka Jefferson National Expansion Memorial) continue this story of the expansion of the United States from coast to coast and the clash with Native Americans.

The parks also teach us about the diverse ethnic heritage of the United States, from African Americans and Alaska Natives to American Indians, Asian Americans, and others of European and Hispanic roots.

Parks and National Historic Landmarks, such as Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center, Apollo Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center, and a not yet designated historic site, the Santa Susan a, field laboratory, teach us about the history of the American space program. Santa Susana Field Laboratory is a complex of industrial research and development facilities located on a 2,668-acre portion of the Southern California Simi Hills in Simi Valley, California. It was used mainly for the development and testing of liquid-propellant rocket engines for the U.S. space program from 1949 to 2006, nuclear reactors from 1953 to 1980, and the operation of a U.S. government-sponsored liquid metals research center from 1966 to 1998.

The National Park System and its associated preservation programs, such as the National Register of Historic Places, preserve and encapsulate the history of the entire nation. It is this history that the park historian interprets to millions of Americans every year

During the time I worked for Ed Bearss, (NPS chief historian, 1981-1994) Bearss saw that it was the job of the chief historian to be familiar with as many parks as possible. He also tried to meet as many park historians, interpreters, park planners, naturalists, and management superintendent as possible. Ed could claim a personal relationship with many historians, such as Robert Utley, Jerry Greene, Gordon Chappell, Richard Sellars, John Paige, Barry Mackintosh, Harlan Unrau, John Williss, John Paige, and Harry Phanz. Carolyn Pitts, Melody Webb, and Polly Welts Kaufman all published books that are recognized at the best in their field. Mackintosh set the standard for doing park administrative histories, which is still adhered to this day

Pitts published a landmark study of the architecture of Cape May, New Jersey, that resulted in the designation and saving of the architectural heritage of the entire community. Webb wrote A Woman in the Great Outdoors: Adventures in the National Park Service. This book is a classic history of the role of women in the mostly male-dominated ranger ranks.

Gordon Chappell is recognized as the best historian who ever worked on Western railroads. Richard Sellars wrote a classic history of Natural Resources Management in the National Park Service. Jerry Greene is acknowledged to be one of the best historians ever to write about the Indian wars following the Civil War. Harry Phanz’s three-volume history of Gettysburg is a classic and will never be equaled, while Bob Utley is one of the best historians ever to work in the field of Western history. Harland Unrau and John Willis wrote the classic history of the expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s. John Paige’s history of the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service will never be equaled.

Bearss did everything possible to support these historians to see that they were able to do their work. He knew that historians who work for the National Park Service are a different breed of individual.

Their jobs are desirable and therefore highly competitive. A National Park Service historian has to know not only his craft but also his subject matter material. He/she has to meet the public, either through daily tours or public meetings where talks are given and questions asked and answered. Of course, not all park historians can answer all questions, but if there is a lack of historical information on the subject, the NPS historian has to looked into it and do the research. This process does not stop until a satisfactory answer is found and ready for the next meeting. This is all done through interaction with the public. Yes, the park historian writes books and publishes in academic journals, but it primarily though his/her interaction with the pubic that his knowledge and craft are honed to a fine edge.

National Park Service historians may work in more than 400 parks and eight regional offices, but they are a team. They work together, gather at meetings, and compare notes. Everyone meets the public, and there is no better training than interpreting American history to the general public.

Let us work to ensure that the practice of history in our National Park System does not fail. The preservation and interpretation of American history is one of the most important role for the National Park Service to play.

Traveler postscript: How do you think the National Park Service is doing in terms of interpreting history in the parks?

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Al--

I'm not sure downgrading the position of chief historian is politicizing it.

I actually care much less about a NPS chief historian than I do about historians actually in parks. Park historians don't report in a chain of command to the chief historian, so I'm not sure how much a chief historian can do for history in parks. One of CJ's former parks had its historian retire. When I expressed my valuation of historians and asked where updated interp program content would come from, the chief of interp said without a pause: "Harper's Ferry". I expected at least an answer of trying to hire an interp ranger with some history background, essentially downgrading the importance but retaining the capacity. The answer I got stunned me.

Sadly, Historians are being phased out, look at the SE region's CIvil War parks, over the last few years as one retires the position is done away with. Right now, I know of only one Historian left in the region. Fort Sumter gone, Shiloh gone, Vicksburg gone, Kennesaw Mountain gone.

I think the importance and status of the history programs of the NPS has collapsed. Sadly there is no one in the agency speaking out in support of the importance of history. There is no leadership. This decline needs to be reversed but I do not see any way this will happen now until we hire qualified historians and fill vacant positions in our parks.

I've been following, as well as worrying about, this thread for a while now, contemplating the implications of "downgrading the importance" of NPS historians, of who gets hired and placed into these positions, the level at which they're placed in the hierarchy, the educational qualifications they must or may not meet, and the process by which they get to say what they say. I believe history is important; but, more than that, it is powerful. What people are led to see as their history almost automatically becomes their culture. Culture can enlighten and inspire; but, it can also institutionalize ignorance and incite division. It can raise the level of discourse; but, it can also motivate the most perverse, foul, and dangerous forms of prejudice. My experience, firsthand experience, is that, allegedly due to budgetary constraints, the interpretation of history, actually the interpretation of practically everything associated with the NPS, from biology to simple public health and safety, is gradually being monetized and delegated to the concessionaires, as marketable forms of entertainment in most cases. In the hands of an enlightened society, the very act of relating history can ennoble us all. But, privatized into the hands of less enlightened commercial operators or even left to less qualified NPS staff who may have been hired for the wrong reasons, it can slide toward a skewing of the truth. Let me offer some specific examples.

I have a folders of papers on my desk. Among them are certifications, a certification as a naturalist, a certification as an interpretive guide, a certification as a wilderness first responder, and even a certification as a leave no trace trainer. I earned my certification as an interpretive guide, not only on the basis of my knowledge of history, but more on my ability to shape how I conveyed, or did not convey, that knowledge in ways that supported the line endorsed by the concessionaires who actually control the park where I was being certified. It was blatant to the point of actually being amusing. I was coached that the certification was an employment qualification and that, if I wanted the certification, I had to demonstrate my ability to turn serious concepts into a marketable form of entertainment because the role of the interpretive ranger was, again allegedly due to budgetary constraints, giving way to the performance art practiced by the tour guides employed by the concessionaires. It was only slightly better with the process for my naturalist certification. To cope with the sustained erosion of our public schools, I had to prove I could sugarcoat news of an eminent global mass extinction and present it at roughly an eighth grade level.

And, there's the ever present political dimension. I'm not a consistent fan of everything Terry Tempest Williams writes. As with many conservation writers, I find her tendency to appeal to the heart to be more emotional than I tend to be and I find that she struggles with her culture more than either the struggle or the elements of her culture that she struggles with are worth. However, with regard to the comment about the declining presence of NPS historians in "the SE region's CIvil War" units, I'm looking at my copy of her book "Hour of the Land" and recalling the chapter on Gettysburg National Military Park. In writing that chapter, she paints a viscerally evocative picture of efforts to convey history that have gone horribly wrong. The true history of Gettysburg is painful, but also ennobling and uplifting. The story Williams' tells is how reenactors' efforts to turn that history into some form of commercially marketable performance art seem bound and determined to feed and reinforce a toxic culture and incite the worst and most perverse forms of division. Let me give you a couple of other examples of how this happens more widely.

On past occasions, I've related a particular story from my time working in a national park bookstore; please forgive me if you've heard it before. An older woman, dressed in a cowgirl outfit, entered the bookstore one day, glared at our selection of works on Native Americans, voiced belligerent animosity toward Bears Ears National Monument, and loudly endorsed an apparently regional publication that she insisted the bookstore should be selling. By her account, this publication argued that Native Americans were too impaired to progress past the Stone Age on their own, remain inherently impaired today, and thus the government should give them no say in how any land, reservation or otherwise, is managed. This past August, I had another experience that illuminated the episode with the aging cowgirl. I stopped at an NPS visitor center that formerly housed a collection of artistically significant Native American artifacts. As I parked my vehicle and walked toward the building, I passed a yellow school bus where a large man, again dressed in western garb, was unloading what appeared to be just short of a dozen junior high kids. I went on into the visitors center to see that most of the collection had been removed for conservation due to the inadequate humidity control in the building and was looking at the few items left on display when the school group entered and saw the signs about the items that had been removed. At that point, the man leading the group announced that the kids shouldn't be disappointed, explaining that they already knew that the artifacts were silly and primitive and that the government shouldn't be wasting money on preserving or displaying them. I was appalled; but, it didn't stop there. He went on to remind the kids that they already knew that their ancestors had settled the region centuries before the "Lamanites" ever got there and that the government should be displaying artifacts of their culture and not wasting money on preserving or displaying any of the "trashy" stuff from Native Americans.

So, history can be ennobling and uplifting, except when it serves culturally twisted and perverse purposes and shoving NPS interpretive responsibilities onto commercial interests is a sure way to send the wrong message.

Thank you for your thoughtful comments. I am worried about the declining state of history interpretation and research in the NPS. The problem is not just lack of staff and money but the absence of any sort of leadership from the office of the Chief Historian of the NPS. Until we get strong leadership the future will look bleak.

harryb3570

I don't think an administration that treats accurate reporting like replaying video, as "fake news" really wants historians preserving accurate records.

Harry Butowsky, you are correct! We should keep the Office of our Chief Historian of the NPS and their staff strong and active. As Americans, we pride ourselves in honesty; learning from the past, and through true reflection, to build for our Nation's future. The success of the National Park Service Historians is paramount to the preserving our national story, the good, and the not so good. But most importantly, we must continue to document and recognize the true facts of our Nation's history through first hand observations and preservations. Only through accurate internal reflection, documentation, preservation, and accurate examinations of our Nation's past, can we continue to fulfill our nation's goal of promoting unity and freedoms for all. History has taught us time and again, history repeats, and we must continue to learn from the past to build a successful future. It is the Chief Historian's obligation, to continue to document our shared past, such that all who encounter our historical sites, can learn the truth and us build a successful tomorrow.

Hello, I am a prospective MA History student who was planning to go into NPS as a historian? Should I look elsewhere to be a historian? I turned from academia since stable jobs seem to be almost non-existent. Yet from what you all have said, it seems like the NPS is a similar story. But what about the new jobs that come up? It seems like a fair amount of historian positions come up on USA Jobs now and again. I would very much appreciate any advice.