Understanding the historian's role in the National Park System/Buddy Secor

Editor's note: Interpreting history is a key role of the National Park Service. In the following column, former NPS historian Harry A. Butowsky outlines the role of historians in the agency.

The National Park Service takes care of and interprets some of the most powerful and instructive historical places in the nation. Millions of Americans cultivate a deeper appreciation of the nation’s past through encounters with historic buildings and places. A thorough knowledge of our own history is essential in the making of Americans. The study and understanding of American history is important to the preservation of our democracy.

The National Park Service preserves sites of national significance in the evolution of the history of the United States. Our parks represent the key turning points in our history. They help us to understand ourselves as a people and nation in today’s complex world.

The Park Service historian is the keeper of the essence of American history. Unlike the academic historian who spends his life in the classroom and has never worked in government or business and spends his time in lectures and reading history to classes of undergraduate students, the Park Service historian meets the American people every day. Their audience is the nation. They are the ultimate student of history. They read all of the significant literature pertaining to their subject, and also walk the ground where it occurred. In many cases, they also interview the key people who have taken park in the history of their site.

The Park Service historian is not only a teacher and interpreter, but also the best subject matter specialist on the history of his park.

As individuals, communities, and countries, we are nothing without the fabric of history. History gives meaning to the stories of our lives. It provides the fabric upon when we can all stand to assess the present and hope for the future.

The National Park Service preserves this function for the nation.

The National Park Service preserves the key turning points in American history. At Independence National Historical Park, visitors learned how the 13 colonies changed and evolved into an independent nation based on the principles written in the Declaration of Independence. The park visitor also learns how only a few years later the newly independent states came together again to write the U.S. Constitution and created the most successful document for government in human history.

At Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, the visitor learns how America finally came together with the promise of equality embodied in the Declaration and the Constitution and outlawed the practice of segregation forever. Brown v. Board represents the fulfillment of the ideas of the Declaration and the Constitution and the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments of the Constitution.

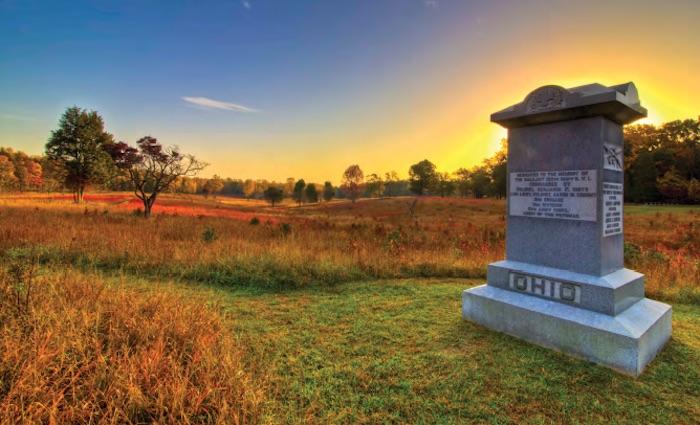

Similar lessons are learned from out many other parks. From Fort Sumter to Antietam, Vicksburg, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Petersburg and finally Appomattox, the visitor learns how America fought a terrible Civil War to preserve the unity of the nation. They learn how more than 600,000 Americans died in this struggle and why it is important today.

From Lowell National Historical Park, Americans learn of the early path of the nation to becoming the industrial power that is the marvel of the world today. From Pullman National Monument they learn of the price American workers paid in the evolution of the Industrial Revolution.

From the homes of the many presidents and other prominent Americans preserved, they learn the importance of these men and women who guided the nation throughout its history. Walking the grounds of Franklin D. Roosevelt's home at Hyde Park in New York, the Eisenhower National Historic Site, or the Harry S Truman National Historic Site gives a new dimension to understanding these prominent Americans.

Visiting the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal teaches Americans of the first movement of the colonies to the west. Other parks, such as Arkansas Post National Memorial Site, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Gateway Arch National Park (aka Jefferson National Expansion Memorial) continue this story of the expansion of the United States from coast to coast and the clash with Native Americans.

The parks also teach us about the diverse ethnic heritage of the United States, from African Americans and Alaska Natives to American Indians, Asian Americans, and others of European and Hispanic roots.

Parks and National Historic Landmarks, such as Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center, Apollo Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center, and a not yet designated historic site, the Santa Susan a, field laboratory, teach us about the history of the American space program. Santa Susana Field Laboratory is a complex of industrial research and development facilities located on a 2,668-acre portion of the Southern California Simi Hills in Simi Valley, California. It was used mainly for the development and testing of liquid-propellant rocket engines for the U.S. space program from 1949 to 2006, nuclear reactors from 1953 to 1980, and the operation of a U.S. government-sponsored liquid metals research center from 1966 to 1998.

The National Park System and its associated preservation programs, such as the National Register of Historic Places, preserve and encapsulate the history of the entire nation. It is this history that the park historian interprets to millions of Americans every year

During the time I worked for Ed Bearss, (NPS chief historian, 1981-1994) Bearss saw that it was the job of the chief historian to be familiar with as many parks as possible. He also tried to meet as many park historians, interpreters, park planners, naturalists, and management superintendent as possible. Ed could claim a personal relationship with many historians, such as Robert Utley, Jerry Greene, Gordon Chappell, Richard Sellars, John Paige, Barry Mackintosh, Harlan Unrau, John Williss, John Paige, and Harry Phanz. Carolyn Pitts, Melody Webb, and Polly Welts Kaufman all published books that are recognized at the best in their field. Mackintosh set the standard for doing park administrative histories, which is still adhered to this day

Pitts published a landmark study of the architecture of Cape May, New Jersey, that resulted in the designation and saving of the architectural heritage of the entire community. Webb wrote A Woman in the Great Outdoors: Adventures in the National Park Service. This book is a classic history of the role of women in the mostly male-dominated ranger ranks.

Gordon Chappell is recognized as the best historian who ever worked on Western railroads. Richard Sellars wrote a classic history of Natural Resources Management in the National Park Service. Jerry Greene is acknowledged to be one of the best historians ever to write about the Indian wars following the Civil War. Harry Phanz’s three-volume history of Gettysburg is a classic and will never be equaled, while Bob Utley is one of the best historians ever to work in the field of Western history. Harland Unrau and John Willis wrote the classic history of the expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s. John Paige’s history of the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service will never be equaled.

Bearss did everything possible to support these historians to see that they were able to do their work. He knew that historians who work for the National Park Service are a different breed of individual.

Their jobs are desirable and therefore highly competitive. A National Park Service historian has to know not only his craft but also his subject matter material. He/she has to meet the public, either through daily tours or public meetings where talks are given and questions asked and answered. Of course, not all park historians can answer all questions, but if there is a lack of historical information on the subject, the NPS historian has to looked into it and do the research. This process does not stop until a satisfactory answer is found and ready for the next meeting. This is all done through interaction with the public. Yes, the park historian writes books and publishes in academic journals, but it primarily though his/her interaction with the pubic that his knowledge and craft are honed to a fine edge.

National Park Service historians may work in more than 400 parks and eight regional offices, but they are a team. They work together, gather at meetings, and compare notes. Everyone meets the public, and there is no better training than interpreting American history to the general public.

Let us work to ensure that the practice of history in our National Park System does not fail. The preservation and interpretation of American history is one of the most important role for the National Park Service to play.

Traveler postscript: How do you think the National Park Service is doing in terms of interpreting history in the parks?

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Thanks, Harry!

I'm a natural resources guy. But there are at least 100 historical/cultural NPS units with no natural resources, while _perhaps_ there are a handful of Alaska natural resource parks with little to no history. Also, I assert that most additional NPS units over the next 100 years should be cultural not natural: preserving for future generations aspects of the American experience in the latter half of the 20th century and beyond. NPS needs historians every bit as much as it needs scientists. And as you write above, NPS can be dream jobs for both historians and scientists.

As for how I think NPS is doing interpreting history in parks: my one word would be "coasting". Yet another park historian who just retired won't be replaced by a historian, or even an interp ranger with a strong history background as part of the PD or KSAs. That means no new scholarship or updated history for visitors, no one with specific knowledge to teach interp rangers and park guides, and no one to revitalize the living history program. My impression is that WASO-level history positions are declining, too. Will park interp programs and displays simply get old, or will their updates be contracted out? Apparently, subject matter knowledge is no longer required or even valued for interp rangers: neither the interp chief nor the park guide at that park know the natural resources, either.

I hope that my impressions are biased by what I see myself, and that things are better elsewhere in NPS. Or, that this is cyclical, and historians will become more valued in NPS over the next decades.

Tomp 2

Your comments are correct. The practice of history is declining in the nps. Historians retire every week and are not replaced. We are losing our trained cadre of exprience historians in our parks, regional offices and even in the Washington office. There is no one speaking for our park historians It is all in decline and we are still adding historical parks. The practice of history is not promising for the future of the nps and no one seems to care.

Nicely said.

My wife is a curator/archivist, and her entry to the Park Service a decade or so ago was smoothed by the professionalism and courtesy of several historians. Personally, I believe that her discipline and yours are complementary, and the NPS is properly served by a strong cadre of historians, curators, and archivists. Unfortunately, that isn't exactly what is being funded.

Two words: Imperiled Promise

See: https://www.oah.org/site/assets/files/10189/imperiled_promise.pdf

NPS history is incredibly rich in some areas, abysmally poor in others. The agency does not really support robust history work (or the employment, either permanent or as contractors, of trained historians) at anything like what the resources it shepherds would demand.

Harry, I think what you wanted to say--and pulled your punches--is that the Office of Chief Historian no longer measures up. It used to be a GS-15, and subject to presidential privilege/approval. Now the position is GS-14, and strictly Civil Service, yes? In other words, President Trump cannot touch the Chief Historian, but in the past every president could--and sometimes did. I believe I am right on this, but feel free to correct me.

In any event, who is the Chief Historian now? Who represents all of the ideals you beautifully explain above, and yes, daily assists historians everywhere, both inside and outside of academe? Whoever that historian is has never contacted me. In contrast, all of the people you mention above did contact me at some point, if only to say hello and invite me to visit the office. That is how we met, as I recall. You extended me the invitation having read my books.

It's a big hole in the National Park Service, and yes, no academic will ever fill it. Not that I disparage our colleagues, but the politics of academe get in the way. Just my saying this would get me into "trouble" with the PC Brigade. How dare I question President Obama's decision to demote the Office of Chief Historian and keep it "safe?"

Well, is the office "safe," or now just like academe? I wish I could be optimistic that the Park Service "gets it," but all I see is another retreat from the truth. At least, that is how I interpret politicizing the Office of Chief Historian, but again, do correct me if I'm wrong.

As a bright spot, if I may be so immodest, Yellowstone has kept and filled the historian position. Lee Whittlesey, who retired after decades in the NPS, retired in April 2018. I was hired as his replacement in late May, 2018. Yellowstone is often thought of as a natural park, but we have a strong cultural resources program, are the only park to be a NARA affiliate (so all our records stay here), and our history is closely tied to the history of conservation as a whole. It is a priveledge to work as Yellowstone's historian and I hope to live up to the high standards outlined in this article. That said, there are very few historians in the Intermountain Region.

I wonder what the present Chief Historian has to say about all of this. How does she see the state of history in the NPS.

Park historians are dinosaurs and us aspiring historians in the agency have nowhere to go. We take on dozens of collaterals and make ourselves marketable but we know no matter how much we study and work hard to be the go to subject-matter expert, we will never receive a historian position at our park. Park management has dictated that they need to work with what they are given: no increass in base funding, shrinking staffing and pushing more onto field employees. What happens when new historical resources are folded into the embrace of the agency? The answer: the overtaxed, do-it-all ranger.

I will say a retired park historian tells me to be optimistic. That when he was in the same boat, a superintendent stepped up and reestablished the position as an essential position for the park. Ed Bearss was the Chief Historian at the time and there was a renew emphasis for park historians. Not anymore. There is no advocate for them. We don't need to be GS12/13 at the park level. But a GS9/11 would give us a living wage and a resource a park vitally needs to continue discovering new, diverse stories for the a larger, broader audience.