Stocking the haypile. Arterra/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Andrew Smith, Arizona State University

Stocking the haypile. Arterra/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Andrew Smith, Arizona State University

Climate change is harming many special places and iconic species around our planet, from Glacier National Park’s disappearing glaciers to California redwoods scorched by wildfires. But for the animal I study, the American pika (Ochotona princeps), there’s actually some good news: It’s not as threatened by climate change as many studies have warned.

I have studied pikas, small cousins of rabbits, for over 50 years and never tire of watching them. These tailless, egg-shaped balls of fluff live primarily in cool mountainous environments in piles of broken rock, called talus.

During summer, observers can see pikas industriously gathering caches of grass and leaves into haypiles that will serve as their food supply through the winter. Their light brown coats blend well with their surroundings, so they are easiest to spot when they perch on prominent rocks and call to alert other pikas of their presence.

Pikas’ calls range from short squeaks to a longer ‘song’

When fellow hikers see me observing pikas in California’s Sierra Nevada, they often tell me they have read that these animals are going extinct. I have collected a stack of press releases that say exactly that. But based on my recent research and a comprehensive review of over 100 peer-reviewed studies, I believe that this interpretation is misleading.

Constrained by climate

As I showed in my early research, pikas’ biology suggests that they are likely to be affected by a warming climate. Most important, their normal body temperature is high, and this puts them at risk of overheating when active in warm environments. When temperatures are warm, pikas retreat into the much cooler depths of their talus habitat.

Temperature also plays a role in pikas’ ability to move from place to place. Warm weather inhibits their movements, while cooler temperatures allow them to more freely colonize new habitats.

A little ancient history is instructive here. Pikas originally came to North America from Asia and spread across the continent some five million years ago, during colder times. Their remains have been found in caves in the Appalachian Mountains and in the Mojave Desert – sites where pikas no longer live.

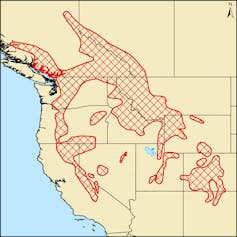

American pikas live mainly in alpine and subalpine mountain areas extending south from central British Columbia and Alberta into the Rocky Mountains of New Mexico and the Sierra Nevada of California. Andrew Smith, CC BY-ND

American pikas live mainly in alpine and subalpine mountain areas extending south from central British Columbia and Alberta into the Rocky Mountains of New Mexico and the Sierra Nevada of California. Andrew Smith, CC BY-ND

As the world’s climate warmed, pika populations retreated to the high mountains of the western U.S. and Canada. Today they occupy most of the available talus habitat in these areas – evidence that challenges the pikas-on-the-brink narrative.

For example, in recent surveys, pikas were found at 98% of 109 suitable sites in Colorado, and at 98% of 329 sites in the central Sierra Nevada. One study of historic pika sites across California’s Lassen, Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia national parks found no evidence that pikas were moving to new sites or higher altitudes due to climate change.

Pikas in warm environments

In contrast, most sites where researchers believe that pikas have disappeared are small, isolated and often compromised by human activities, such as grazing by livestock. These sites generally are lower and warmer than sites in pikas’ core range.

Many of these areas are in the Great Basin – a large desert region spanning most of Nevada and parts of Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Oregon and California. A series of studies on a small number of marginal Great Basin sites formerly occupied by pikas has disproportionately contributed to the narrative that pikas are likely to become endangered.

Pikas have disappeared from some parts of the Great Basin, but climate change may not have been the cause. Kmusser/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Pikas have disappeared from some parts of the Great Basin, but climate change may not have been the cause. Kmusser/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

To investigate the big picture across this region, I worked with state and federal officials on a 2017 study that identified 3,250 site records of pika habitat. Pikas were present at 2,378 sites, not found at 89 sites where they had been seen as recently as 2005, and absent from 774 sites that contained only old signs of pika occupancy.

The extirpated and old sites had the same temperature and precipitation ranges as sites where pikas still were present. This suggests that non-climatic factors may have caused pikas’ disappearance from the vacant sites.

Pikas are still present in other remarkably hot places, such as the ghost town of Bodie, California, the nearby Mono Craters and Idaho’s Craters of the Moon National Monument. At these sites, pikas retreat into the cool nooks of their talus habitat during the warmest part of the day and often forage at night.

In my research, I also found that pikas were much less active and uttered far fewer calls at these low-altitude sites compared with high-elevation pika populations. At low-elevation sites, pikas consumed a diverse diet of Great Basin plants, such as big sagebrush and bitterbrush, that was markedly different from the plants they ate at high-elevation sites. Some even failed to construct their characteristic large haypiles.

Another atypical pika population lives near sea level in Oregon’s Columbia River Gorge. Here, too, they have adapted well to a very different habitat, surviving year-round on a diet that consists mainly of moss. They defend the smallest territories of any pika, and when it gets hot, they simply move off the talus and hang out in the shade of the nearby forest.

Pikas can make dozens of trips daily to build up their haypiles for winter.

A future for pikas

Based on my review of dozens of studies, pika populations appear to be secure in their core range – the mountains of western North America that have large and fairly well-connected talus habitat. In these areas they can move from one habitat patch to another without having to pass through areas that are dangerously warm for them.

The fact that pikas have also adapted to a number of marginal, hot environments suggests to me that they are more resilient to climate change than many past studies have concluded. Most species exhibit losses near the edges of their geographical ranges, simply because individual animals in those zones are living in conditions that are less than ideal for them. This does not mean that they are going extinct.

Climate change is the most critical issue facing the world today, so it is particularly important that scientists communicate accurately about it to the public. In my view, the fact that pikas are coping and altering their behaviors in response to changing conditions is encouraging news for future naturalists setting out to observe one of nature’s most charismatic mammals.

![]()

Andrew Smith, Professor Emeritus of Life Sciences, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments

And, of course, pikas are still common in Denali NPP and other alpine parks and areas of Alaska.