University Hill, on the left, and Carnegie Hill at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument/Kurt Repanshek

Revealing The 20-Million-Year-Old Secrets Of Agate Springs

By Kurt Repanshek

Heading 34 miles north from Mitchell, Nebraska, on a two-lane highway in various states of resurfacing, I cruised across the prairie on a bright Labor Day Weekend morning. On either side of the road, rolling prairie turning gold stretched off into the distance. It's not the sort of setting where you'd expect 20 million years of prehistory to surface.

It was the beauty of that prairie, cut in places by the meandering Niobrara River, that led James Cook in 1886 to take the woman he planned to marry, Kate Graham, on a horseback ride to enjoy the day. It was a day that took the two across the land that soon would be their ranch and which revealed to them a window with a view some 20 million years into the past that came to stun the scientific world.

This was the golden age of paleontology in the West. O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope, two Eastern paleontologists, were at the height of their "Bone Wars," a very personal and ugly battle between the two to see who could monopolize the fossil riches discovered as they crisscrossed Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska. Cook crossed paths with Marsh in 1874 when the paleontologist came to western Nebraska to hunt for fossils and Red Cloud, an Oglala Lakota chief who knew and trusted Cook, asked him if Marsh really was looking for old bones and not gold.

But it was a dozen years later that Cook's name, at least for a while, could be mentioned in the same sentence with those of Marsh and Cope. Walking across the prairie that today is Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, I tried to envision the excitement shared by Cook and scientists from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Yale University in Massachusetts, and Princeton University in New Jersey as they climbed onto the flanks of two adjacent hills above the thin river to collect the fossilized remains of a faunal menagerie.

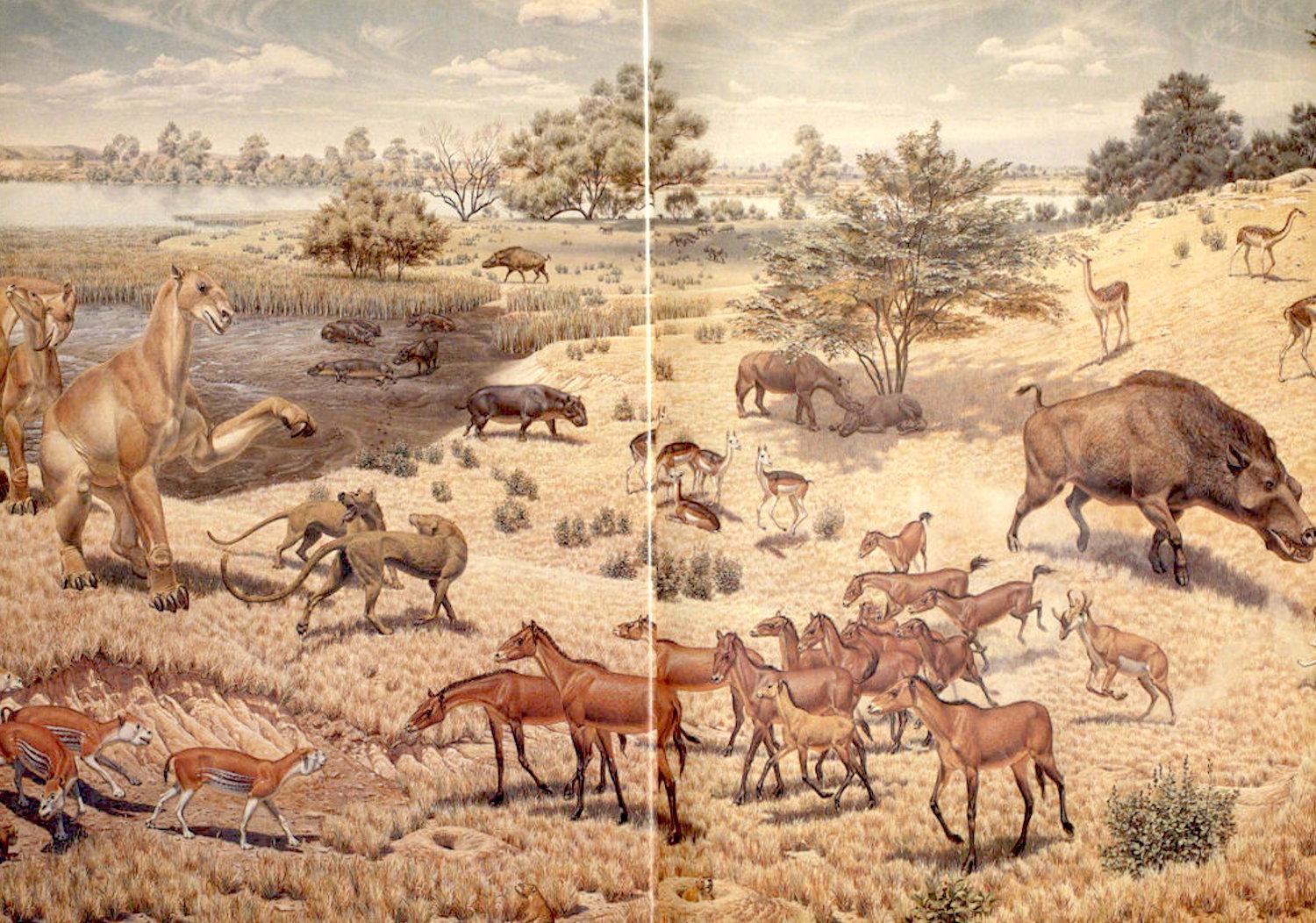

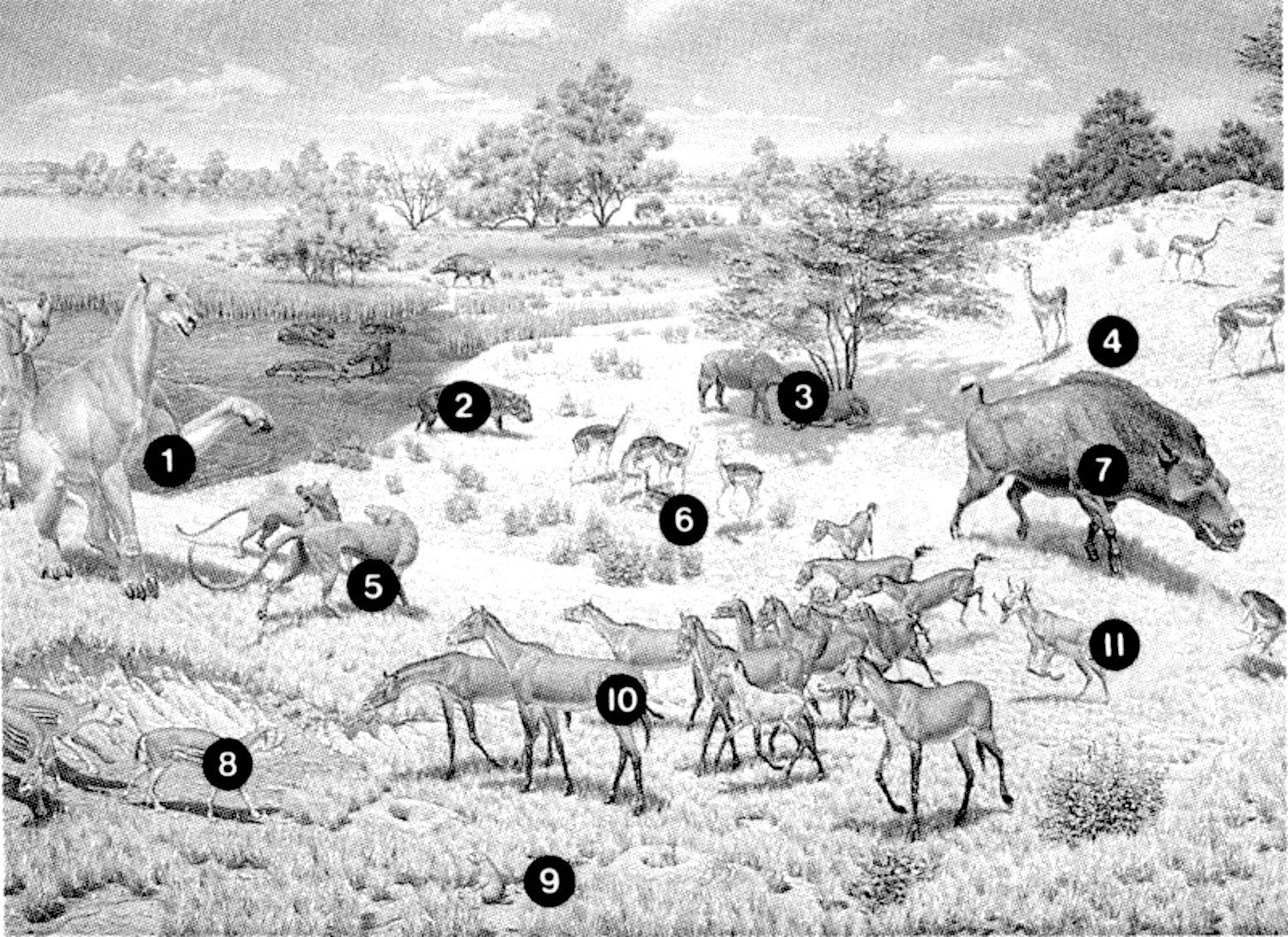

A National Museum of Natural History mural depicts the fauna thought to exist on the landscape of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument during the Miocene epoch.

The treasures they uncovered owed their discovery to Cook and his bride out for a ride across the ranch.

"We came to two high conical hills about three miles from the ranch house. From the tops of these hills there was an unobstructed view of the country for miles up and down the valley," Cook, who would acquire the land from his father-in-law and call it the Agate Springs Ranch, recounted in his autobiography, Fifty Years On The Old Frontier. "Dismounting and leaving the reins of our bridles trailing on the ground—which meant to our well-trained ponies that they were to remain near the place where we had left them—we climbed the steep side of one of the hills. About halfway to the summit we noticed many fragments of bones scattered about on the ground.

"I at once concluded that at some period, perhaps years back, an Indian brave had been laid to his last long rest under one of the shelving rocks near the summit of the hill, and that, as was the custom among some tribes of Indians at one time, a number of his ponies had been killed near his body," he wrote. "Happening to notice a peculiar glitter on one of the bone fragments, I picked it up; and I then discovered that it was a beautifully petrified piece of the shaft of some creature’s leg hone. The marrow cavity was filled with tiny calcite crystals, enough of which were exposed to cause the glitter which had attracted my attention. Upon our return to the ranch we carried with us what was doubtless the first fossil material ever secured from what are now known to men of science as the Agate Springs Fossil Quarries." (Note: The monument took its name from the ranch, not for agate fossils, though there are some there.)

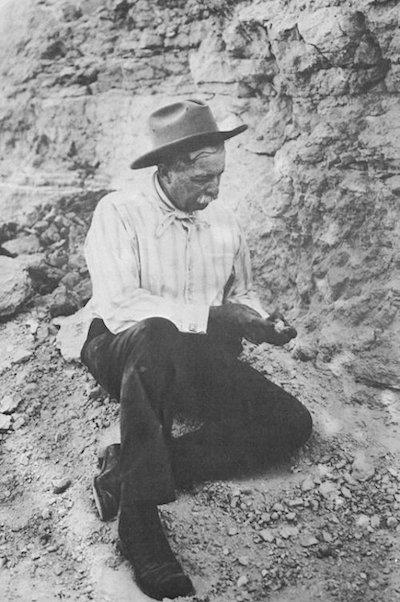

James Cook, examining fossils, around 1918/NPS archives

Despite the fossil chase that was underway in the West, it took nearly 20 years for Cook to convince scientists that his newfound boneyards were worth studying. While Professor Erwin Barbour from the University of Nebraska came out 1891 and 1892 to collect fossils from the surface, it was not until 1904 when Professor Olaf Peterson came out from the Carnegie Museum to see what Cook had found that serious digs began. Peterson's finds spurred other scientists, including those from Yale, Amherst College, and the American Museum of Natural History among others, to join in the bone rush.

Today the hills and the surrounding prairie don't seem terribly noteworthy; there are no jouncing, heavily-laden wagons heading downhill with drivers straining on the reins to hold back the horses, no explosions such as those used a century ago to uncover fossils. The hot sun and the shadeless ground remain, however.

What Cook and his wife had happened upon were burial grounds of prehistoric animals that evidently had died around a vanishing waterhole. The creatures pieced together by the scientists were both docile appearing and terrifying. Among the myriad remains were those of Stenomylus, two-foot-tall camel-like creatures, Menoceras, a three-toed animal similar to today's rhinoceros, Dinohyus, a carnivore whose name means "terrible pig," and also remains of the wolf-like Daphoenodon, another carnivore referred to as "beardog" that preyed on the others.

"The fossil bones which I discovered in Nebraska, at the place on the Niobrara River where I later made my home, proved to be the clew (sic) which led, then, to a veritable house of records," wrote Cook. "In those twin hills, during the early Miocene period of the earth’s history, the remains of vast numbers of the creatures which then inhabited that great flood plain region were deposited under hundreds of feet of sediment."

After viewing the monument's short orientation film that lays out Cook's initial fossil find and then the race of paleontologists, I headed out from the visitor center to the not-quite-three-mile loop trail that took me on a boardwalk across a wetlands created by the Niobrara River and slowly but steadily uphill to the two hills that so astounded science more than a century ago. The day's steady breeze kept the bugs away, but the mixed grass prairie offered no shade from the sun overhead in the cloudless sky. What the prairie did offer was habitat for prairie rattlesnakes, which I successfully managed to avoid.

The cement Fossils Hills Trail (manageable by wheelchairs), as it's called, twists in loops around the hills, taking you directly in front of where the diggings took place. But rather than heading straight for the hills, I detoured down a mile-long trail that crosses the prairie to the simply named "Bone Cabin" that Harold Cook, Jame's son, erected in either 1908 or 1909 to leverage the Homestead Act to legally acquire the land so the family could have better control over the fossil digs. Today the ramshackle-appearing cabin appears to be a tiny conglomeration of rooms that might have been detached from other cabins and nailed together here a bit below the hills named University and Carnegie for the paleontological teams that dug there. Rising above the cabin is a windmill for the ages, one that spins in the wind but no longer draws water, as it once did for the scientists and their laboring crews.

The "Bone Cabin" today/Kurt Repanshek

After Harold "proved up" his homestead, he returned to his father's more comfortable ranch house, and the structure was turned over for use by the bone diggers. Though the Park Service has stabilized the building and restored its look to how it probably appeared in the early 1900s, it's locked tight with no access.

Reversing course, I headed back a short ways to a trail junction that sent me uphill along another path the Park Service keeps mown across the prairie to reach the hills. I soon found myself standing in front of Carnegie Hill's eroding hip.

My untrained eye struggled to spot any fossil bits that might have remained embedded in the hillsides or eroded out by a century of storms. Placards made it easier to envision the chore of recovering fossils a century ago. During the height of the diggings, between 1904 and 1923, the fossil recovery wasn't as carefully done as it is these days. At times dynamite blasted away overburden to reach the two-foot-thick fossil bed. Then, crews used picks and shovels to carve out large stone blocks containing fossils, cover them in plaster, and then use a tripod lift to wrestle the blocks onto horse-drawn wagons to be taken downhill.

Fossil replicas on display in the visitor center/Kurt Repanshek

Returning to the visitor center, I got a closer view of replica skeletons that make it easier to envision the animals that the disappearing waterhole had kept locked in the ground for millions of years.

"In those twin hills, during the early Miocene period of the earth’s history, the remains of vast numbers of the creatures which then inhabited that great flood plain region were deposited under hundreds of feet of sediment," Cook explained in his book. "Minerals in solution, in the form of calcite, silica, and manganese, were abundant in this sediment. As the organic matter in the skeletal parts of the animals were brought in with the sediment by the floods, and disintegrated molecule by molecule, these minerals in solution entered and, in time, transformed the bones into stone."

Backtracking from the visitor center to Nebraska 26, I stopped at the entrance to the national monument and hiked up the mile-long Daemonelix Trail to view a very unusual burrow, a corkscrew one dug by the Paleocastor, described as a sort of dryland beaver that lived here during the Miocene. The burrows that spiral 6- to 8 feet straight down are believed to have offered these large rodents some measure of defense against predators that roamed the plains.

Two of these fossilized burrows are protected today by plastic shelters, one that looks much like a telephone booth. The second shelter, if you hike the trail clockwise as suggested, is truly unique, as it protects a single burrow that, at the bottom, splits into two dens.

Despite being somewhat off the beaten path in a corner of the National Park System, Agate Fossil Beds is only an hour's drive west from Scotts Bluff National Monument, and certainly worthy of tacking on to a park journey that also includes Fort Laramie National Historic Site nearby in Wyoming.

Key to the museum mural. 1/Moropus, 2/Promerycochoerus, 3/Menoceras, 4/Oxydactylus, 5/Daphoenodon, 6/Stenomylus, 7/Dinohyus, 8/Merychyus, 9/Palaeocastor, 10/Parahippus, 11/Syndyoceras/NPS archives

Comments

Great report.

Those Daemonelixes are the darndest looking structures.

Also, don't miss the exhibits of the Cook collection of artifacts he collected from several Indian tribes