A plan to more than double visitation to Cumberland Island National Seashore has raised concerns over the impacts to the park's natural resources and visitor experience/NPS file

Cumberland Island National Seashore officials are open to more than doubling the allowable number of visitors to the park that straddles Georgia's largest barrier island, a decision that has raised concerns that the National Park Service is straying from the very reasons behind the seashore's establishment back in 1972.

The proposal, which is open to public comment through November 30, barring an extension, places recreation at a higher priority than resource protection, believes Jessica Howell-Edwards, the executive director of Wild Cumberland, a nonprofit dedicated to "protecting the wilderness, native species, and the ecology of Cumberland Island.

"I think that this is a unique [park] unit, particularly being the largest barrier island wilderness," she said this past week. "I know that it's complex to balance that dual mandate of both protecting and promoting the parks. That's something that the parks have increasingly struggled with under increased use. And it's apparent to all of us, but prioritizing the visitor experience for the future of the seashore, without prioritizing resource protection first and foremost, if not in tandem with it, is really concerning."

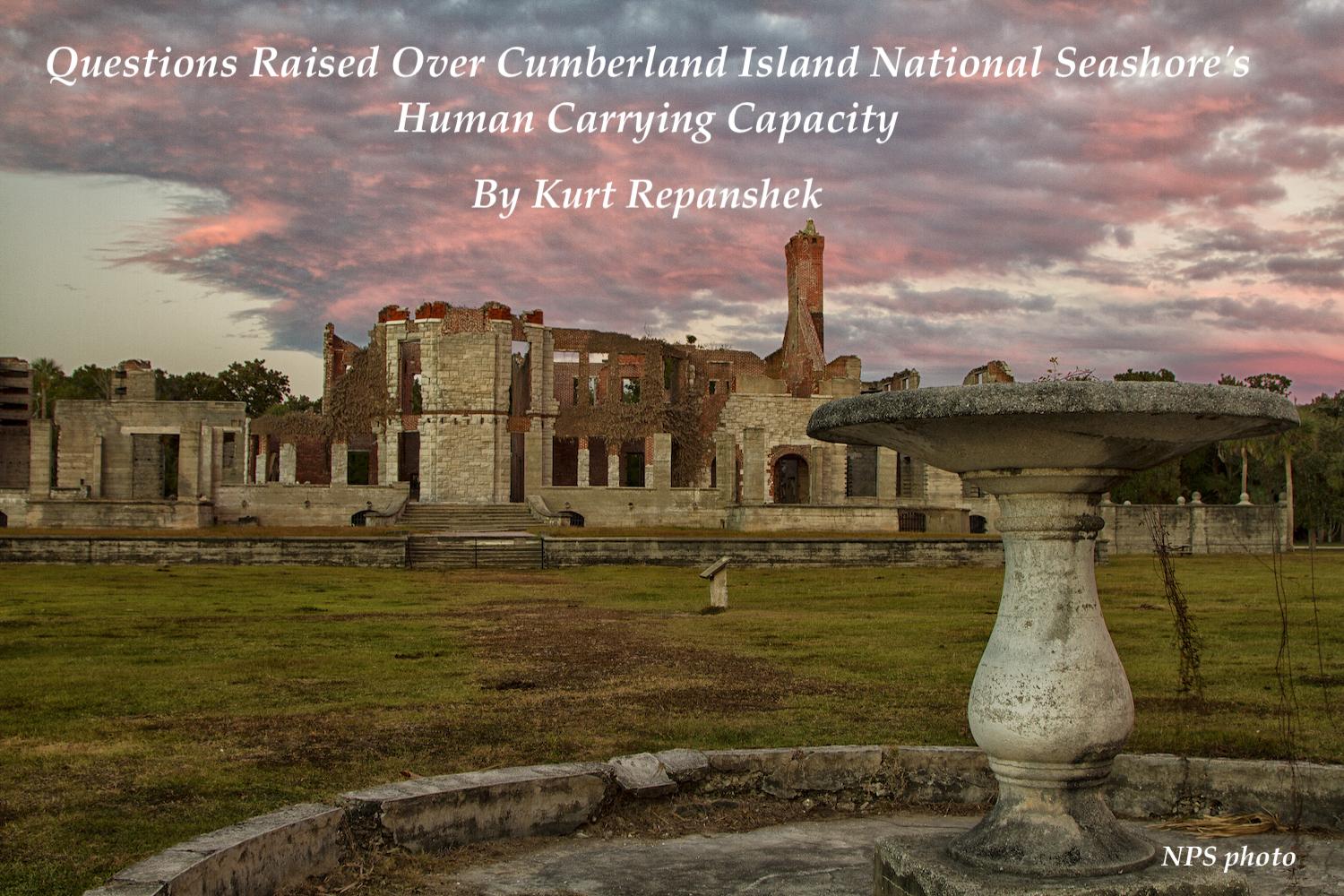

Cumberland Island, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, offers an unusual mix of cultural, historical, and natural resource features. The Dungeness Historic Area interprets the ruins of a mansion built in 1884 for Thomas Carnegie (the younger brother and business partner of Andrew Carnegie), his wife Lucy, and their 9 children. The 22,000-square-foot Plum Orchard Mansion was built in 1898 as a wedding gift for George Lauder Carnegie and Margaret Thaw and is open for tours. There are acres and acres of maritime forest that harbor live oaks draped with Spanish moss that rise over an understory of Saw palmetto, hollies, grapevine, and Virginia creeper, while white-tailed deer, armadillos, feral horses, and wild hogs roam the island. There are roughly 18 miles of beachline that attract loggerhead turtles for nesting; on the northern end of the island stands the First African Baptist Church, which was built in 1893.

Under the national seashore's general management plan, which was adopted in 1984, daily visitation to the park has been held to "approximately 300 people per day." The Park Service's preferred alternative in the visitor use management plan now open for public review says that approximately 600 people per day could be allowed to enter the national seashore via the Dungeness and Sea Camp docks, and another 100 people per day to the Plum Orchard dock if ferry service was available.

"These changes would be implemented adaptively, meaning the park would monitor key indicators to ensure sensitive shorebirds are protected, as are visitor opportunities to experience the rustic atmosphere, quiet solitude, and wilderness character described by visitors and public commenters. Adjustments would be made based on this monitoring," a park release said.

The Dungeness Ruins, the skeletal remains of a mansion that burned down in 1959, are part of the island's rich human history/NPS file

Some visitors to the national seashore say the Park Service is struggling to manage current visitation. They say ranger presence can be fleeting, trash is an issue, some visitors chase after the feral horses for a selfie, kids climb onto the ruins at Dungeness. Between Fiscal Year 2000 and Fiscal Year 2021, the seashore's staff dropped from 34 full-time employees to 30, while the annual visitation climbed from 44,954 to 72,240. The visitors are drawn to largely wild setting of more than 36,000 acres, including nearly 10,000 acres of Congressionally designated wilderness and another 10,710 acres of potential wilderness, a rather large swath of island for visitors to disperse through during their explorations.

"I think given visitation and what we're seeing in the park, there's been such a massive uptick across the country, it's not very surprising to see [the Park Service] really kind of looking at Cumberland Island and thinking about how they can allow more visitors access there," said Emily Jones, the Southeast regional director for the National Parks Conservation Association. "We're glad that they're stepping up and addressing this top-level need for parks all across the country, and this needs to evolve. I think that probably with this uptick [in allowed daily visitation] -- and there's a lot of other things within that plan that will help resource management -- I think that they're going to get some pushback, by and large. But 700 people a day does not seem to me to be unrealistic."

The Traveler has reached out to Cumberland Island National Seashore Superintendent Gary Ingram for comment.

Protecting natural resources in the seashore is key. As the seashore's Foundation Document states, the Park Service mission is to "maintain the primitive, undeveloped character of one of the largest and most ecologically diverse barrier islands on the Atlantic coast, while preserving scenic, scientific, and historical values and providing outstanding opportunities for outdoor recreation and solitude."

That document also noted that the 1984 general management plan [which is not posted on the park website] for the seashore sought to cap daily visitation to 300 per day so as to both provide "outdoor recreation in an uncrowded, undeveloped setting" and to maintain the island's relative isolation to "to preserve and protect the island’s fragile natural and cultural resources."

The draft visitor use management plan recognizes those goals, stating that the plan "should enhance visitor access to the wilderness area, while preserving wilderness character. Wilderness character at the park includes opportunities for solitude and natural, untrammeled, and undeveloped qualities."

While Howell-Edwards acknowledges the plan seeks to maintain wilderness quality, she also worries that it doesn't specifically outline how it will under increased visitation.

The draft plan, she noted, calls for allowing wilderness access at Plum Orchard, which is farther north on the island than the current access point at Stafford, the access point called for under the 1984 GMP. That new access point will make it easier for eBike users to get into the official and potential wilderness areas, creating user conflicts with hikers, said Howell-Edwards. Plus, she said, "to me, it's a visitor risk for those who are not equipped to really go into wilderness and encounter a 10-foot alligator walking your trail, and having to treat their water and things like that. So, it's a really complex thing. Increasing recreational access to the wilderness also changes the experience quite a bit.

"I think that people choose Cumberland for the isolation and sort of that more remote, isolated experience," she went on. "Adaptive management can be an effective tool, but this plan doesn't really detail how and when they will make change in the event that they monitor or observe impacts to the resource or the visitor experience."

The plan does call for greater dispersion of wilderness users through the creation of two new backcountry campsites, at Toonahowie and Sweetwater Lakes, coupled with the closure of the Yankee Paradise sites. Beyond that, the park staff will be monitoring visitor use and adjusting access depending on impacts to resources, both natural and cultural, NPCA's Jones said.

"The other thing, too, is there's a desire to want to create space and place for people who maybe don't traditionally visit Cumberland Island National Seashore, because you have so many great stories. Everybody knows the stories that the Carnegie's, but they don't necessarily know the stories of the Indigenous people, they don't necessarily know the stories of the Freedmen's colonies that were there. There's so much more over there than the story of the industrialists and their summer homes. So, it'll give them an opportunity, I think, to open the park up and provide for fitting groups and other organizational groups to come in.

The not-quite 300-page draft plan also calls for creating an area roughly 1,900 feet wide on the southern tip of the island for private boats to park, and calls for a showerhouse that would require installation of 2,670 feet of water utility line and possibly 1,850 feet of electrical line. That facility would require a roughly 1,200-square-foot septic leach field. You can find the plan, study its details, and comment on this page.

With the comment period squeezed into one month, a month that features Election Day as well as the Thanksgiving holiday break, Wild Cumberland, Sierra Club Georgia Chapter, Georgia Audubon, Center for a Sustainable Coast, St Marys Riverkeeper, Wilderness Watch, Wild Alabama, One Hundred Miles, and National Parks Conservation Association have called on the Park Service to extend the comment period to 90 days.

Add comment

Support National Parks Traveler

Your support for the National Parks Traveler comes at a time when news organizations are finding it hard, if not impossible, to stay in business. Traveler's work is vital. For nearly two decades we've provided essential coverage of national parks and protected areas. With the Trump administration’s determination to downsize the federal government, and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum’s approach to public lands focused on energy exploration, it’s clear the Traveler will have much to cover in the months and years ahead. We know of no other news organization that provides such broad coverage of national parks and protected areas on a daily basis. Your support is greatly appreciated.

EIN: 26-2378789

A copy of National Parks Traveler's financial statements may be obtained by sending a stamped, self-addressed envelope to: National Parks Traveler, P.O. Box 980452, Park City, Utah 84098. National Parks Traveler was formed in the state of Utah for the purpose of informing and educating about national parks and protected areas.

Residents of the following states may obtain a copy of our financial and additional information as stated below:

- Florida: A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR NATIONAL PARKS TRAVELER, (REGISTRATION NO. CH 51659), MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING 800-435-7352 OR VISITING THEIR WEBSITE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE.

- Georgia: A full and fair description of the programs and financial statement summary of National Parks Traveler is available upon request at the office and phone number indicated above.

- Maryland: Documents and information submitted under the Maryland Solicitations Act are also available, for the cost of postage and copies, from the Secretary of State, State House, Annapolis, MD 21401 (410-974-5534).

- North Carolina: Financial information about this organization and a copy of its license are available from the State Solicitation Licensing Branch at 888-830-4989 or 919-807-2214. The license is not an endorsement by the State.

- Pennsylvania: The official registration and financial information of National Parks Traveler may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling 800-732-0999. Registration does not imply endorsement.

- Virginia: Financial statements are available from the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 102 Governor Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219.

- Washington: National Parks Traveler is registered with Washington State’s Charities Program as required by law and additional information is available by calling 800-332-4483 or visiting www.sos.wa.gov/charities, or on file at Charities Division, Office of the Secretary of State, State of Washington, Olympia, WA 98504.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

The wilderness is not Disneyland. Nature is not just another form of human entertainment.

This is America and it runs on money. The best way to preserve Cumberland is to steadfastly enforce wilderness standards in the wilderness area -- including the ban on vehicles, including bicycles, and limit access to the rest of the island to off-road feet.

And for goodness sake, stop letting a handfull of super-priviledged, entitled eliteists hold the fututre of what should be the crown jewel of the SE natural coast hostage -- enforce eminent domain to secure all lands on the island, and pay a fair price. Put one example of government integrity on the books.

The Plan does not call for a 1,900 square foot dock south of Sea Camp, it calls for restricting boat landing to a specific beach section to avoid nesting shorebird habitat.

Good catch, Michael. We've corrected it.

During my occasional visits to Cumberland Island, it is clear the staff is NOT effectively mantaining it, such as boards missing from the boardwalk, etc. I do not see how they can manage a bigger and more complex park. I also feel they are kidding themselves if they think the increased visitors will be spread out over the new accesses, when it is obvious they will be concentrated in the small south end sites that attract most visitors. This approach has overwhelmed other national parks and I fear it will overwhelm Cumberland Island too.

I believe To increase the daily visitors to the Island by more than double was never the intent of the this National Seashore. Has anybody studied the impact to the Island just by trash people leave behind? The wildlife including the horses will be the one who pay for all this! At least have a system in place before you allow such increase! You are supposed to protect this National Treasure...