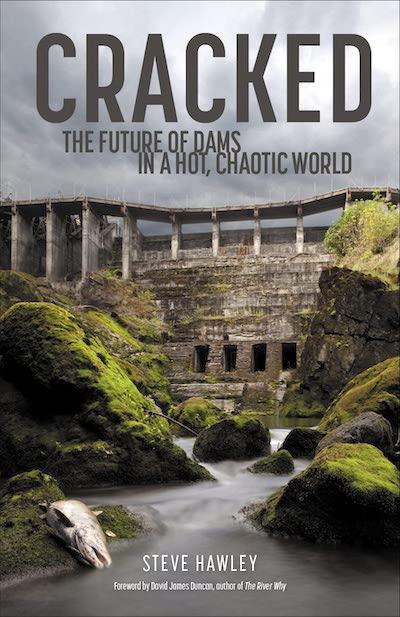

Patagonia Books, a publisher with a clear mission, releases reasonably priced (this hard bound book lists for $28), profusely illustrated, solidly written works that aim to “inspire and restore a connection to the natural world and encourage action to combat climate chaos.”

Cracked is such a book, taking on the big and complex issue of dams, their impact on rivers worldwide, the weakening rationales for maintaining dams already built or for building more, and how people are working with some success to “crack” these monolithic structures.

Some dams have been symbolically cracked, like Glen Canyon Dam, and some physically cracked, like the dams on the Elwha River in Olympic National Park. In his Foreword, David James Duncan of The River Why fame writes, “Steven Hawley has written, and Patagonia has brilliantly supported, an undamming book powerful beyond anything I thought possible in a time of cynicism, greed, and cave-troll politics. Cracked is itself a mass-breaching of the lies, corruption, and betrayals that have fueled the insane parade of dam-building by disembodied bureaucracies and totalitarian governments worldwide.”

A mighty strong and justified endorsement.

Cracked is illustrated throughout with full color photographs, and on page 16 is a shocking photo of a dense cheek-to-jowl housing development, the caption for which reads, “Las Vegas sprawl is reliant on Colorado River water. What will happen when the water runs out?”

This development is a warren of nearly identical houses surrounded by a sere brown desert with no vegetation in sight. It requires Colorado River water, and the developers squeezed every house they could into their rectangular plot of desert regardless of whether such water would be assured from an already over-allocated river.

The words in this book are powerful, but the photos strongly amplify those words. Two hundred pages later, in a chapter titled “Drain Powell First,” in bold print is the following: “Las Vegas is building a $1.4 billion dollar drainpipe into the bottom of Reservoir Mead, so that, when it reaches dead pool, the fountains at the Bellagio will keep on pumping.” Hawley doesn’t refer to “Lake Mead” or “Lake Powell” as in common parlance because both are reservoirs, a nice touch.

Cracked is unapologetic, fact filled, readable, advocacy journalism. Hawley makes clear his stance and intention in the first paragraph, writing, “This book was written with a reliance on one of the basic tenets of good faith in the written word; that interested readers may extrapolate to the universal from the examination of the specific. Your home water may not be depicted here, but the patterns of destruction that come with any dam-building regime are as recognizable as the American flag, and as reliable as the sunrise.”

He begins with a “speed date” of 100 years of Western American water control and the politics thereof, starring the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation. The role dam-building has played in violation of Native American rights and abrogation of treaties is highlighted, as is the role dams played in America’s splitting of the atom. Readers cannot but feel outrage reading the 50 pages of this chapter of fraught American history.

Next Hawley focuses on a specific case of the way dam-building has violated Native Americans, the example being the tribes of the lower Snake River where four dams were completed between 1961 and 1975. The dams buried sacred sites and blocked salmon migrations to a vast habitat, putting long-term sustenance of any salmon runs on the Snake River at risk and egregiously ignoring Native traditions. Why were these large and relatively recent dams built? Hawley writes, “Columbia River dams have played a starring role in manufacturing vast fortunes for corporate America, with companies like Alcoa, Weyerhauser, Boeing, and Google all profiting handsomely from cheap hydropower. Dams created wealth out of water for European immigrants who arrived to farm newly irrigated land, and in subsequent generations, made millions for corporate agriculture ventures.”

Reader outrage grows in these early chapters.

To give relief, Hawley inserts “Interlude: Getting the Garden Back” describing removal of the Condit Dam on Washington’s White Salmon River. He shares a river journal entry as he watches the free-flowing river pass below him. “Free-river advocates are part of what writer Paul Hawken in Blessed Unrest describes as the civil society movement. Over one million groups — from the smallest nonprofit to major international NGOs — are all doing their level best to preserve or create wilderness, peace, justice, clean air and water, healthy food, access to health care, gender equality, and the atmosphere surrounding our planet that supports life. Tearing down old dams and preventing new ones deserves recognition among these many worthwhile causes.”

Watching a river return has many benefits, not the least of which is that it “restores faith in the cycles of nature, including human nature, in an age when loss of faith in nature happens all too quickly.” The White Salmon story is an antidote to outrage, calming the reader, at least temporarily.

After this respite, Hawley moves on to discuss the future of the Colorado River. He briefly reviews the history of its dams, a familiar story to anyone who has paid any attention to water in the American West, then explains some of the issues less covered, such as evaporation from reservoirs in the desert, sediment traps behind the dams, and how dams add methane to the atmosphere, contributing to the global warming crisis.

Throughout the book Hawley interviews experts who have been working to document the problems associated with dams, and his discussion of the methane problem features interviews with John Harrison, a Washington State University professor who is a leader in the field of studying reservoir methane emissions. Hawley concludes that, “hydropower and the sprawling water storage and delivery systems of the twentieth century are nowhere near as clean and green as hydropower advocates have claimed.”

Professor Harrison says, “In every system where we’ve measured methane emissions, reservoirs are producing methane and releasing it to the atmosphere.”

Hawley thinks Glen Canyon Dam should go.

Because it threatens not only the health but the flowing existence of everything downstream of it, because it loses through evaporation five times more water every year than Denver uses, because it drowned Glen Canyon, because its bathtub ring rivals the height of the Statue of Liberty, because its marinas are silting in — Reservoir Powell is a growing mess. Like all man-made messes, the longer it takes to reckon with the disaster, the harder it will be to clean up.

On the facing page is a color photo of a buoy that reads, ironically, “No Boats” and sits “high and dry on cracked earth that was previously under the water of Reservoir Mead, June 2022.” Point made!

After this Hawley goes on juxtaposing good and bad news on the dam front. He describes many dam disasters, such as the collapse of the Teton Dam in Idaho and the Vaiont Dam in Italy that wiped out the village of Longarone and killed at least 2,000 people. But in the latter part of the book, good news outweighs the bad. Progress is being made on dam removal in the Klamath Basin, a struggle that has been raged for decades.

The Elwha River on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula is a dam removal success story, two dams taken out and salmon returning to the pristine habitat in Olympic National Park from which they were blocked for a century. But not entirely a success story, as Hawley explains problems associated with fish hatcheries, one of which the Elwha Klallam tribe insisted be built as part of the dam removal. Hatcheries are another issue, threatening wild salmon runs, and in Hawley’s view, wild salmon should be the priority.

The chapter “Patagonia Sin Represas” tells the story of the battles in Chile to keep dams off the Baker River that were ultimately successful, a campaign in which Americans Doug and Kris Tomkins played a role. Hawley tells this epic story well. He interviews Juan Pablo Orrego Silva, known as “the John Muir of Chile.” He quotes Peter Hartmann, another activist in Chile.

“When Juan Pablo was organizing the protests of the Biobio Dams, most people thought he was just some crazy man talking about stopping dams. Now of course he is the most often quoted spokesperson for the Sin Represas campaign. That he’s taken seriously is a tribute to how far the movement has come.”

Sin Represas (Patagonia Without Dams) is a coalition of community groups and national and international NGOs that launched the campaign against Patagonia dams in 2009. Five dam permits in Aysén were cancelled in 2014, but “as David Brower observed, all environmental victories are temporary, and all defeats permanent.” Aysén is a vast unroaded section of Patagonia, and activists doubt dam builders will give up. The campaign continues.

Orrego has practical advice for leading fights against water exploitation but believes that the defense of beauty is “as important as the practical directives he issues about the nuances of networking.”

“The defense of beauty is behind everything we do.” says Orrego. “When you bring up the idea of beauty with industry people, they tend to get very sarcastic. If you ask, ‘Why do you want to destroy such a beautiful thing?’ They‘ll accuse you of sentimentality, of having emotional problems. But I’m an ecologist. And I’ve been thinking about these kinds of rebukes. The fact is when you see an ecosystem, because it's complex, because its diverse, somehow beauty is an external manifestation of ecosystem health and integrity. But beauty also is an important part of human mental health. We need beauty to be really healthy internally.”

As he flies out of Chile, Hawley reflects on Orrego’s vision of a “still-attainable earthly paradise” in places which, by luck or design, have avoided industrial development and might be more than refuges. He writes, “If they exist by design, if the human history of their defense is taken into consideration, they could double as blueprints for rebuilding a better world, a map for the way out of the ruins. It’s possible.”

Writers covering stories like the one Hawley has embraced need hope, and he finds some in Orrego’s thought and work.

Design for protection of places like Aysén takes work, of course, so Hawley includes a chapter titled “Dam Removal 101.” This is an excellent overview of strategies and tactics, from assessment of whether the dam you wish to remove is a reasonable candidate, to organizing campaigns, to the arcane subject of permits — lots of good information.

Hawley includes a section on “Small Dam Removal Success Stories.” He quotes Sam Mace, who was a leader of the effort to remove the lower Snake River dams.

“Dam removal is about building consensus. It’s about saying ‘yes’ to an alternative view of the future of a river. Consensus building around a ‘yes’ is more complex than building a critical mass of people saying ‘no’ to something — no to development, no to clear-cutting, no to drilling. Both kinds of activism are important. The only way to do it is to keep forging relationships, keep the conversation going, especially with people who you don’t see eye-to-eye with right away.”

Throughout this book Hawley’s stories offer examples of what Mace says here, people at odds eventually finding some common ground and getting to “yes.” Organizing for dam removal, Hawley contends, is “a grassroots organizing project, an endeavor in door-to-door diplomacy, a revival of the practice of community-level democracy to which politicians are always vaguely alluding, and which the vast majority can’t quite seem to remember how to perform.”

Cracked is an excellent book, at once enraging and inspiring. Tim Palmer, author of many books about American rivers, says of it, “Steve Hawley has cracked and shattered the myth that dams have universally served us well. His informed outrage at the unnecessary loss of natural rivers is outdone only by his sense of hope for a better path.”

That path seems steep, but the stories of dedicated, persistent, and informed people taking on the climb is inspiring. Any of us with dams in our places that should go (and the map on pages 24 and 25 clearly shows that there are probably some near you), should get this book, read it for inspiration and ideas, and get to work.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment