Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Shaul Hurwitz, research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

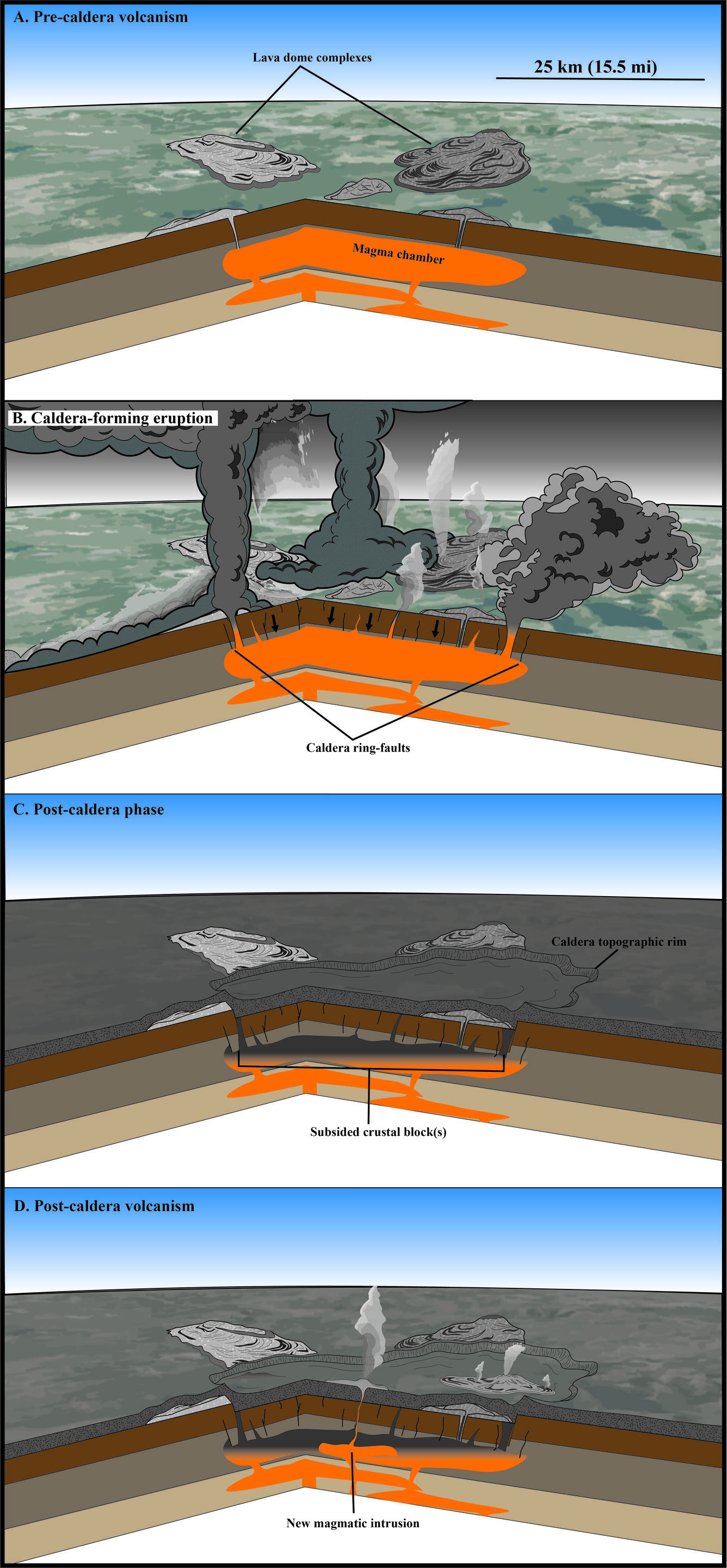

Based on geologic mapping and dating of minerals, we know that the Yellowstone caldera formed 631,000 years ago. But how did the caldera collapse? Observations and monitoring data from several caldera collapses at other volcanoes in the 20th and 21st centuries provide clues.

Many concepts and models used for explaining past caldera-forming eruptions and subsequent collapses were formulated by USGS scientist Robert L. Smith and his colleagues, mainly based on their work at Valles caldera in New Mexico. Subsequently, USGS scientist Peter Lipman’s research at Tertiary calderas of the San Juan Mountains in Colorado illuminated many fundamental processes linking large-volume eruptions and caldera collapses. Geologic mapping by USGS scientist Bob Christiansen suggested that the collapse of the Yellowstone caldera 631,000 years ago in response to the eruption of about 1,000 cubic kilometers (240 cubic miles) of magma occurred within hours or days.

However, recent field observations indicate a more complicated story of large caldera forming eruptions.

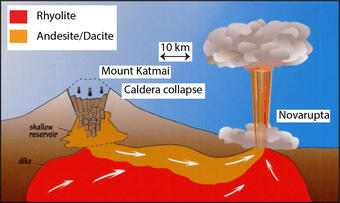

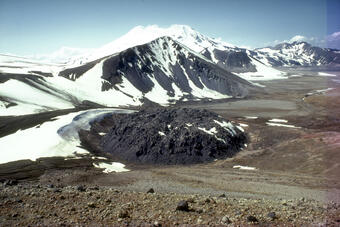

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the establishment of volcano monitoring networks allowed scientists to capture several caldera collapses in unprecedented detail. One of the best examples is from the 2018 eruption of Kīlauea Volcano on the Island of Hawai’i. Data collected with seismometers, tiltmeters, high-rate Global Positioning System (GPS) stations, and gas sensors helped document precursory activity, growth of the caldera, and subsurface lateral magma transport from Kīlauea‘s summit to the eruption site in the volcano’s Lower East Rift Zone, not unlike what occurred at Katmai and Novarupta 106 years prior. Over the three months of the eruption, the caldera at Kīlauea‘s summit subsided by more than 500 meters (1640 feet).

Many types of monitoring instruments captured the onset of subsurface magma transport, the evolving geometry of the subsiding caldera and its faults, and the amount of magma erupted during the 2014–2015 collapse of Bárðarbunga Caldera under the Vatnajökull glacier in Iceland. As at Katmai and Kīlauea, magma propagated laterally in the subsurface away from the caldera, erupting 1.5 cubic kilometers (0.35 cubic miles) of basaltic magma at Holuhraun, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) to the northeast.

Other caldera collapses in the 21st century that were captured by volcano monitoring networks include the 2000 collapse at Miyakejima Volcano in Japan and the 2007 collapse of Dolomieu crater at Piton de la Fournaise Volcano on Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean. Because of the increasing capacity to monitor volcanoes from space, even the 2018 eruption and caldera resurgence (in contrast to collapse) at the remote Sierra Negra volcano in the Galápagos Islands (Pacific Ocean) were documented in great detail by multiple instruments.

The ability to capture and document caldera collapse with modern monitoring networks provides scientists with diverse datasets to improve upon the early models proposed by Smith, Lipman, Christiansen, and others. Although a massive caldera-forming eruption like the one that resulted in Yellowstone caldera has never been witnessed, geologists can use modern examples, coupled with insights from the geologic history of the Yellowstone region, to better understand how caldera collapse occurs.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places