Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Michael Poland, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey and Scientist-in-Charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

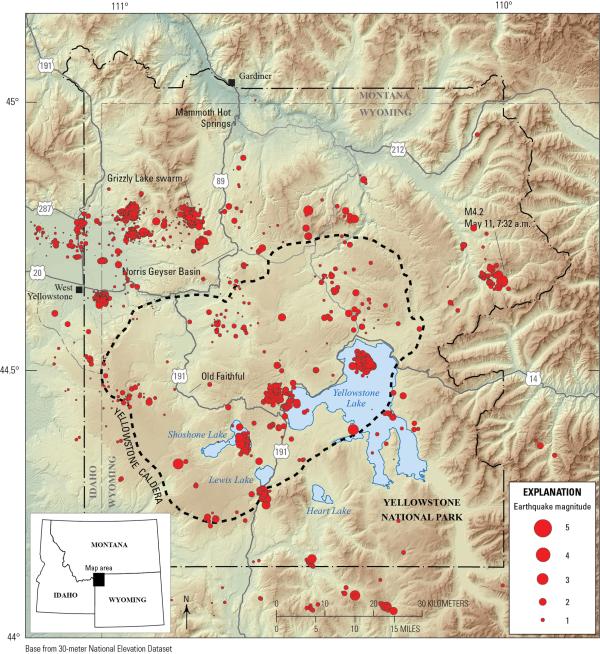

As most Yellowstone geology aficionados are aware, earthquakes are pretty common in the region—1500–2500 events are typically located by the University of Utah Seismograph Stations every year, with about 99% M2 or below. In 2023, seismicity was on the low end of that range, with a bit over 1600 located earthquakes. The largest was a M3.7 event on March 29.

Map of seismicity (red circles) in the Yellowstone region during 2023. Gray lines are roads, black dashed line shows the caldera boundary, Yellowstone National Park is outlined by black dot-dashed line, and gray dashed lines denote state boundaries.

And as is also typical, about half of the earthquakes occurred as part of swarms—sequences of earthquakes that occur in roughly the same place in rapid succession. The two most significant swarms of 2023 both occurred in March. One included 147 located earthquakes (max M2.7) a few miles east-southeast of West Yellowstone, MT, while the other included 106 events (max M3.7) beneath the north part of Yellowstone Lake. These swarms are generally driven by interactions between groundwater and existing faults.

Ground deformation patterns continued trends that have been ongoing since 2015—namely, subsidence of the caldera by about 1 inch (~3 cm) per year. The subsidence is interrupted in summer months as snowmelt and runoff recharges groundwater, causing the surface to swell like a wet sponge, but downward motion resumes by late summer or early fall. No significant deformation was recorded in the area of Norris Geyser Basin during 2023.

Geyser activity was also relatively calm. Major water eruptions of Steamboat Geyser continued to decrease in number, as they have since the record-setting show in 2020, when 48 eruptions occurred. The year 2023 saw "only" 9 eruptions of the geyser (most recently on December 30!). It was not all about geysers going to sleep in Yellowstone, though. Giant Geyser, in the Upper Geyser Basin near Old Faithful, erupted on November 23, 2023—the first eruption of that geyser since a sequence of numerous eruptions during mid-2017 to early 2019.

The only noteworthy hydrothermal unrest of the year occurred in May–June, when some previously dormant features became active, and new features formed, on Geyser Hill, also near Old Faithful. This resulted in part of the boardwalk in the area being closed to visitors—hot water and debris were splashing onto the walkway—but the activity soon waned, and the boardwalk was reopened by early August. The sequence had some similarities to 2018 unrest in the same general area and is a good reminder of the dynamic nature of Yellowstone’s geyser basins.

Thermal feature UNNG-GHG-17a, not far from Sponge Geyser on Geyser Hill in Upper Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park. The feature formed during a period of thermal unrest that began in May 2023 and threw debris and hot water onto the adjacent boardwalk, which was closed for safety. National Park Service photo by Kiernan Folz-Donahue, May 31, 2023.

Unlike the earthquake activity, ground deformation, and most geysers, Yellowstone Volcano Observatory scientists were definitely not calm in 2023. Geologists continued studying the Lava Creek Tuff—the thick, compressed ash deposit left by the most recent caldera-forming eruption at Yellowstone. Layering in the deposit and the recognition of new geologic units are a testament to the complexity of this large eruption.

Researchers also studied Steamboat Geyser, dating wood fragments from long-dead trees that were embedded in the geyser’s sinter deposits. The ages of the wood indicate that the geyser has been active for hundreds of years—far longer than the formation date of 1878 as claimed by Philetus Norris, second superintendent of Yellowstone National Park and namesake of Norris Geyser Basin.

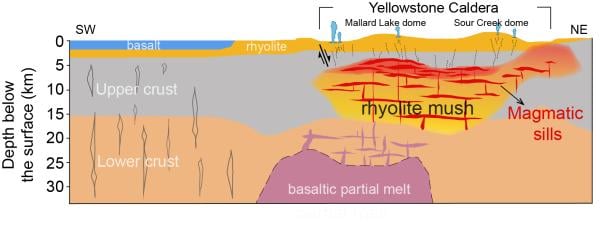

In addition, the magma chamber beneath Yellowstone caldera continued to come into greater focus. In 2020, hundreds of seismic stations were deployed throughout the park. Data from these stations were used to map the seismic wave speeds in the subsurface, providing a picture of the structure of the magma system. The results indicate that the top of the magma complex is characterized by horizontally elongated areas of localized magma storage, called sills, and that magma is stored in a sheet-like manner, instead of being evenly distributed within the rock matrix. After accounting for the textural fabrics, the melt fraction was estimated to be up to 28% in this region of the magma chamber.

Schematic model of Yellowstone’s subsurface magmatic sill complex based on seismic data collected in 2020. The presence of magmatic sills with higher amounts of melt—about 28%—compared to their surroundings is revealed by data collected from a dense deployment of about 650 3-component (capable of measuring vertical and horizontal motion) seismometers in Yellowstone National Park during August-September 2020. Adapted from Wu et al. (2023).

Field work also included the usual station maintenance to ensure that remote equipment remained operational throughout the year. New satellite communications technology was installed at a few sites, offering better connectivity for some monitoring stations. And at Norris Geyser Basin a brand-new monitoring station was installed—one that includes microphones that can “hear” geyser activity. Stay tuned for more information about this exciting new collection of data!

Happy New Year! From all the members of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory consortium, take care, be safe, and best wishes for 2024.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places