Elizabeth Valencia remembers swimming through a steel bulk freighter, the Chester A. Congdon, submerged at Isle Royale National Park, a remote island archipelago on Lake Superior in Michigan. Transporting wheat from Ontario, Canada, the ship smashed into Canoe Rocks in November 1918, several days before World War I ended.

“The bow is still in pretty good condition. It’s open, you can look around and pretend you’re driving the ship,” and also see the pilot house equipped with pots, pans, dishes and other items lodged about 75 feet below the water surface, said Valencia, the interpretation and cultural history manager at the national park.

Ten shipwrecks, all listed on the National Register of Historic Places, are underwater at Isle Royale. Some like the Kamloops, found in 1977 at a depth of 195 feet about 50 years after it wrecked, require technical equipment and a scuba diving permit to visit. Parts of other wrecks, such as the America, a steamship ferrying passengers between ports in Michigan and Chicago from 1898-1928, rest from two to 80 feet below the surface and can be seen by kayak. Wrecked in 1928, the America was “the Greyhound bus and truck service of its day,” said amateur historian Dan Fountain.

The America on the bottom/NPS

Across the country, the National Park Service, in tandem with the states, manages an underwater world dotted with shipwrecks seen only by those who take the time, including divers, historians, treasure hunters (pilfering is illegal) and everyday visitors interested in the stories the wrecks tell.

“We find amazing historic things,” including rolls of Life Savers candy still in a wrapper, boxes of leather shoes, toothpaste tubes, and bathtubs, said Dave Conlon, chief of the National Park Service’s Submerged Resources Center, the underwater archaeology team responsible for documenting and interpreting what they find, including shipwrecks, sunk airplanes, and coral. The parks too have their own dive teams — Valencia used to be on Isle Royale’s.

Joshua L. Marano is on the dive team for national parks in south Florida where more than 5,000 shipwrecks, including several thousand in the Florida Keys, have occurred. The wrecks don’t look like those depicted in movies such as The Goonies or Scooby Doo cartoons where the sails flap in the current, said Marano. Instead, the ships break down, frequently becoming habitat for fish and other marine organisms.

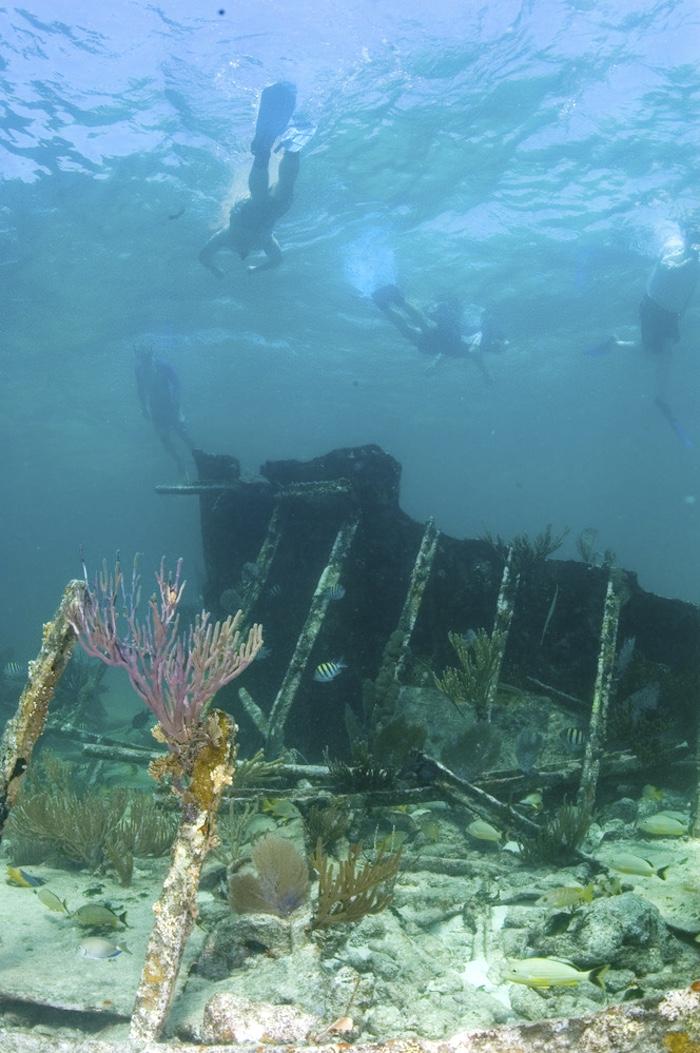

At Biscayne National Park in Florida, a maritime heritage trail guides visitors to five mapped and moored wrecks occurring from 1878-1966. Snorkelers can swim around the Mandalay and the Arratoon Apcar, while the Erl King, Alicia and Lugano wreckages are only available to scuba divers. A boat is needed to get to all five wrecks.

Snorkelers can explore the Mandalay in Biscayne National Park/NPS

For now, the Windjammer, a large, iron-hulled wreck on Loggerhead reef, south of Loggerhead Key, is the only interpreted wreck at Dry Tortugas National Park in Florida. Formerly called the Avanti, the ship sank in 1907 on its way to Montevideo, Uruguay, from Pensacola, Florida. Today, the ship rests at a depth of 20-25 feet below the water’s surface but parts jut above the water line and can be seen from a boat.

Efforts are underway to interpret other wrecks for the public at Dry Tortugas, said Marano, an archaeologist who dives to submerged cultural sites throughout the year. Since joining the National Park Service as an intern in 2012, he has witnessed how warming waters and storms with increased intensity can erode and scour the marine environment.

The Windjammer “used to be absolutely covered in a beautiful coral reef that has been dying off to the extent that I don’t recognize it anymore,” he said.

Heading back to Lake Superior, also home to Apostle Islands National Lakeshore in Wisconsin and Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore in Michigan, there have been up to 550 shipwrecks — more than one half still have not been found — and many remain in decent shape.

The water temperature three feet below the Lake Superior’s surface hovers in the upper 30s Fahrenheit year-round

“It’s like a giant refrigerator, keeping everything in-tact,” said Edward Jakaitis, cultural resources program manager at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore.

Most wrecks on Lake Superior require donning a dry suit — that’s what Valencia wore to see the Congdon and another wreck, the Glenlyon, where a buoy connected to the ship’s stern sits on a sinker 50 feet below the lake’s surface. The Glenlyon’s bow has never been found.

“Lake Superior is well known for its rough waters and storms that come through. While some days are placid, the weather can change very abruptly,” said Jakaitis.

The Glenlyon wreck/NPS

In the 19th century before radar, captains tried to steer their ships during storms toward the leeward side of the Apostle Islands, away from the winds, for protection. But they didn’t always make it, and some got stuck on shoals and beaches, Jakaitis said.

Today there are five shipwrecks — Savona, Noquebay, Lucerne, Fedora and Pretoria, dating from 1872-1900 — listed on the National Register of Historic Places at what is now Apostle Islands. It’s possible to canoe or kayak out to the Fedora, a bulk cargo steamer that wrecked in 1889, resting below the water line along the shoreline of the Bayfield Peninsula, said Jakaitis.

East of Apostle Islands about 250 miles lies Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, known as the “Shipwreck Coast” or “Graveyard Coast” due to the rocky cliffs, sand dunes and fog creating treacherous conditions for mariners, said Hannah Bradburn, the park’s public information officer and visual information specialist.

There have been hundreds of shipwrecks recorded in Pictured Rock's vicinity but three — the Mary Jarecki, Sitka and the Gale Staples — marked with a sign on the lakeshore saying “shipwrecks this way” are offshore Au Sable Point. Located near Hurricane River Lower Campground, the Mary Jarecki was a wooden steamer that wrecked in 1883 while carrying iron ore from the Upper Peninsula.

“Today, you can see beams and the bottom hull of the boat with nails sticking out. Sometimes people don’t always know what they are looking at because they’re expecting a full boat but that’s not what is still around anymore,” said Bradburn.

The Sitka wrecked in 1904 and the Gale Staples in 1918 but both wreckages have intermingled making it difficult to delineate the two. Parts wash ashore, as shipwrecks often do.

Across the country, North Carolina’s coast is known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” due to the estimated thousands of wrecks that have occurred there, said Jami P. Lanier, deputy chief of cultural resources at Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

“Back in the day in the age of sail, the currents off our coast were like highways for merchants,” said Lanier.

Captains would use the Labrador current that runs north to south and the Gulf Stream running south to north to travel efficiently. But this was a risky maneuver, she said. The two streams converge at Diamond Shoals, a shallow underwater sandbar on the Outer Banks and the site for many shipwrecks.

A hurricane grounded the G.A. Kohler at Cape Hatteras in 1933/NPS file

Only those wrecks that sit above the beach’s low tide line, such as the G. A. Kohler that ran ashore in 1933 during a hurricane, are National Park Service property, Lanier said. Located north of Salvo, North Carolina, the ship “appears and disappears” based on the currents.

The vast majority of the shipwrecks in N.C., including the Oriental, a Civil War transport vehicle that sunk in 1862 offshore Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, are the state’s responsibility. Most require scuba gear to access them.

Like the G.A. Kohler, remnants from the schooner Tay used to be visible on Sand Beach at Acadia National Park in Maine.

“In January 2024, sustained high water levels and repeated flooding from high tides moved the wreck, which broke apart as it battered against the exposed, rocky floor of the beach,” said Amanda Pollock, the park’s public affairs officer in an email.

The bones of the Tay, which seem to come and go with the seasons and the storms/NPS

Aside from photographing, measuring and mapping the timbers, park staff attached tags with a QR code or URL to the wreck’s larger pieces, as part of the Shipwreck Tagging Archaeological Management Program (STAMP), a partnership of federal and state agencies focused on tracking shipwrecks and timbers. Now, anyone who comes into contact with a tagged shipwreck remnant can scan the QR code or download the URL to provide information about the wreck’s whereabouts

“With the help of visitors, the fate of the Tay can now be more closely followed,” Pollock said.

Wrecks have been documented in the waters near Fire Island National Seashore in New York since 1954, said Elsa Toman, museum technician at the William Floyd Estate on park property. Park records show shipwrecks have been suspected in the area since the 18th century.

Some wrecks, such as the Bessie White and the Glückauf appear from time to time on the seashore's beaches. Like Acadia National Park, Fire Island participates in the STAMP program.

Even inland parks, such as Yellowstone National Park, have shipwrecks. The frame of the E.C. Waters rests onshore Stevenson Island in Yellowstone Lake, said Michael Poland, the U.S. Geological Survey’s scientist-in-charge at Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, in an email.

One of the first people to benefit monetarily from the park’s natural resources, the boat’s owner, E.C. Waters, was unable to obtain to obtain a license for the 500-passenger steamship to carry passengers on Yellowstone Lake due to his reportedly unscrupulous business practices in running another ship, the 125-passenger Zillah. A caretaker responsible for the E.C. Waters, estimated to cost almost $2 million in today’s dollars, died of a heart attack after rowing the boat to Stevenson Island where it now rests, according to the USGS.

Throughout the country, Park Service staff stress the importance of researching shipwrecks before heading out to see them.

“No one should take on diving activities without adequate training and support. All wrecks should be treated as sensitive irreplaceable resources,” said Jakaitis.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

There is a great book

Underwater Wonders of the National Parks : A Diving and Snorkeling Guide Paperback - December 29, 1997

available from Amazon (and possibly your local library), which outlines not only the shipwrecks, but also many other underwater wonders in our National Parks.