Gnarly and wizened, she can’t compete with Crater Lake’s impossibly blue beauty. Nor does she try as she stubbornly clings to life at the edge of the caldera. They quietly call her the Grandmother Tree but don’t mark the spot where she stands with her name or story.

Far from the lake and away from the crowds, a woman’s sensual form is carved into a boulder. The Lady of the Woods is quietly celebrated, at least by those who find the forest trail that bears her name.

And then there’s the Old Man, an unusual log that calls North America’s deepest lake home.

Crater Lake National Park is considered Oregon's crown jewel and people come to marvel at the brilliant blue water/Jennifer Bain

At Crater Lake National Park — an Oregon park that celebrates a volcanic mountain that collapsed and became an astounding lake — this tree, this rock and this log have stories to tell.

“You’ll notice she has some tags on her,” ranger Bruce James said as the Crater Lake Trolley rolled to a brief stop in front of the Grandmother Tree. “These are not just random messages left by hikers. That is actually a chemical to trick the pine beetle into believing that the tree is so full of pine beetles that it would be a waste of their time to attack it further.”

The Grandmother Tree is a whitebark pine that’s at least 500 years old and one of the oldest trees in the park. This keystone species tolerates the severe conditions at the park’s highest elevations but is under attack from mountain pine beetles and white pine blister rust. The tags tacked to her bark are pine beetle repellent verbenone pouches.

The pouches tacked on to the Grandmother Tree are a pine beetle repellant/Jennifer Bain

Whitebark pines, which can look more like thick shrubs than trees, have less resistance to mountain pine beetle attacks than other species. And now that climate change is allowing beetles to live through milder winters, there are two cycles of egg-laying adults each year instead of one. “More beetles mean more larvae, which consume the phloem layer of trees, cutting off the flow of nutrients,” the park service explains.

Many whitebark pines — a threatened species — are dying a five-stage death from blister rust. But there’s room for optimism.

Two decades ago, park botanists launched a long-term monitoring program and began collecting cones. Now, under the Whitebark Pine Conservation Program, seedlings are grown from the collected cones and tested for resistance to blister rust at the USDA Forest Service’s Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Oregon.

Ranger Bruce James joins a Crater Lake Trolley tour in September/Jennifer Bain

“We gather seeds from these seemingly healthy trees and take them to the nursery, and we’re propagating seedlings and we’re bringing those seedlings back into the park,” James explained.

“That group of trees we saw at Rim Village — all about the same age, 10 years old — that is an experiment. This is unheard of. You never hear of a national park reforesting. Our motto is we finally learned to leave nature alone. Leave it to itself and respect it. But this is just repeating what nature does. It’s natural selection. We’re not modifying the seed in any way and we’re hoping that this new generation of trees will grow up, produce seeds that will pass on that resistance, and enable us to maintain that species in the park.”

It's heavy stuff for what one might expect to just be a photo-friendly romp around the park. The ranger did lighten the mood by talking about the Grandmother Tree’s best friend.

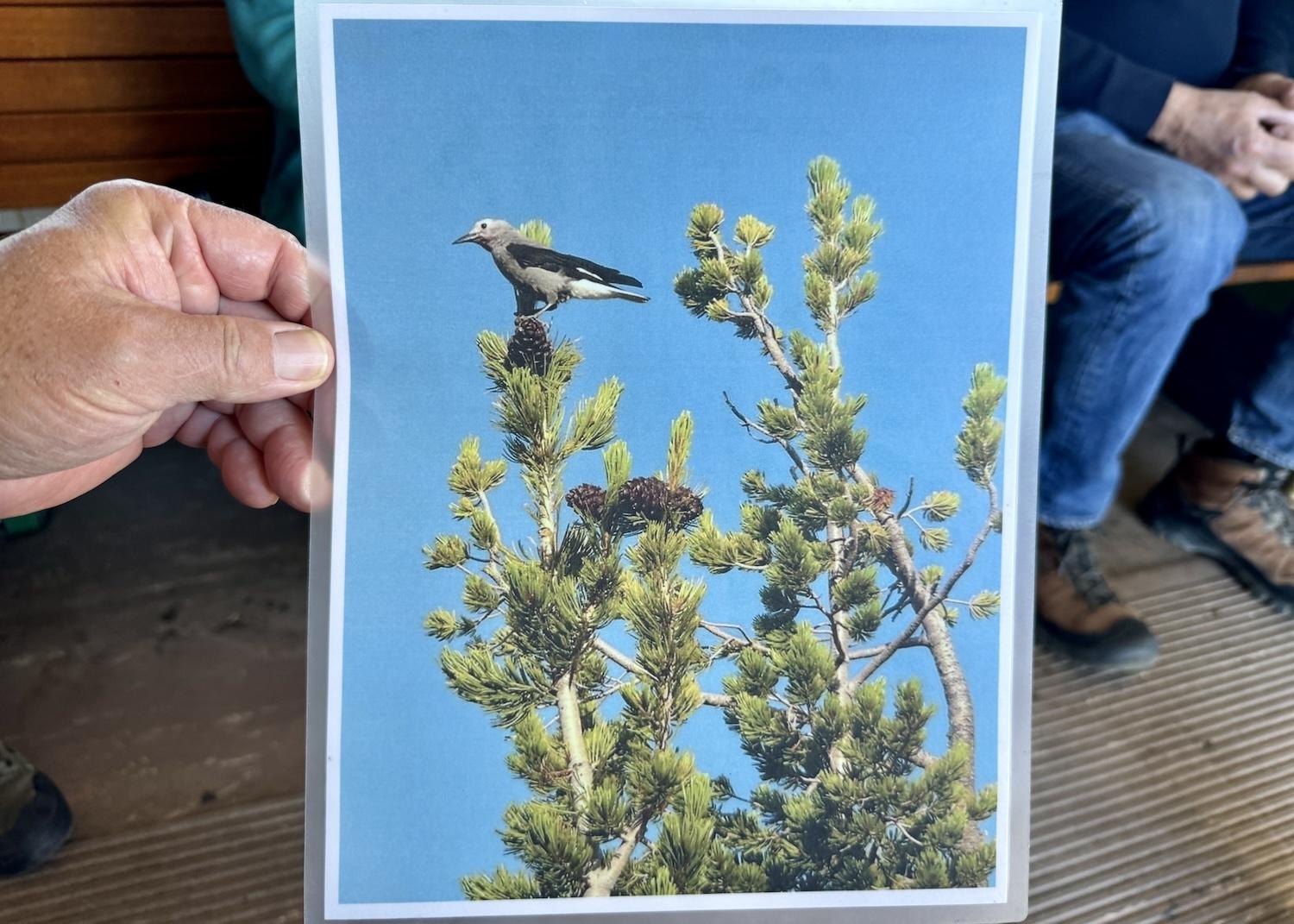

On a trolley tour, a ranger passes around a laminated photo of a Clark's nutcracker. The bird has a symbiotic relationship with whitebark pine trees/Jennifer Bain

Clark’s nutcrackers have powerful beaks and are the only bird that can break into whitebark pine cones. Squirrels, bears and other mammals can also open these cones — which remain closed through maturity — and extract seeds.

“When the Clark’s nutcracker is gathering seeds, it doesn’t eat every seed,” James explained. “It has a pouch under its tongue and it can actually gather up to 90 seeds at a time. In the early spring when the snow is melting, it has noticed where the snow is thinnest in the late fall and that is where it will cache its seeds. And it will dig down two or three inches to cache the seeds ant the most advantageous location for recovery during the winter.”

Jokingly, the ranger added: “The Clark’s nutcracker has a memory like mine. Sometimes it will forget where it cached those seeds.”

On a trolly tour, a ranger passes around a cone from a whitebark pine tree/Jennifer Bain

Forgotten seeds can grow into clusters of whitebark pines, a keystone species that tolerates full sun and grows in previously treeless areas. It encourages plants and animals to follow suit, and regulates snowmelt by shading and retaining snowpack, which slows erosion by anchoring soils in place.

The Grandmother Tree had no cones left that September day that I met her, but James passed one around the trolley explaining that its nutritious seeds have an “astronomical calorie count” and are similar to the pine nuts we use for pesto. They are naturally resistant to spoiling and were once turned into a butter or paste with dried fruit and grease by Indigenous people.

At another pullout, while others admired the lake, I stared sombrely at the carcass of a whitebark pine taken out by blister rust. James spotted a Clark’s nutcracker on it but I only captured shots of inquisitive Gray jays before the birds flew away. At least there were golden-mantled ground squirrels around, fattening up for their winter hibernation.

It was no Clark's nutcracker, but this Gray jay was spotted on the limb of a dead whitebark pine/Jennifer Bain

The trolley — which runs on compressed natural gas — usually circles the 33-mile Rim Drive for two hours but we stuck to West Rim Drive and ogled Crater Lake from multiple viewpoints while learning its back-story.

It was formed about 7,700 years ago when a volcano called Mount Mazama erupted. Rock and lava collapsed into the mountain’s center, creating a massive caldera in place of the 12,000-foot peak. The caldera slowly filled with rain and snow to become Oregon’s crown jewel. A small eruption formed Wizard Island, the park’s “volcano within a volcano.”

The lake is 1,943 feet deep and a a geological oddity because no streams or rivers flow in or out. The water is a striking blue because it’s so clean and deep. Storms drop an annual average of 44 feet of snow leaving the park blanketed in white for eight long months each year.

A view of the pullout where the Grandmother Tree quietly sits along West Rim Drive/Jennifer Bain

“We like to say it’s 1.1 miles down and 11 miles up,” James joked about the one trail that leads down to the marina and water. “It’s the equivalent of climbing 65 storeys.”

Boat tours, some that let you explore Wizard Island, had ended for the season and there was no way I was jumping in that cold, deep lake. Cleetwood Cove Trail is now closed for upgrades until 2027.

The Grandmother Tree, should you wish to find her, is on West Rim Drive at an unmarked pullout facing the lake between North Junction and Devil’s Backbone.

It's not marked but this experimental plot of whitebark pine trees can be found at Rim Village/Jennifer Bain

The trolley ride ended in Rim Village across from the experimental whitebark pine plot. Had the ranger not told us what was going in that unmarked area, we would have walked by it oblivious to its significance like most people do.

Crater Lake drew 559,976 visitors in 2023, which means busy roads and packed parking lots, but isn’t nearly as high as it should be.

“We’re in the middle of nowhere,” Explore Southern Oregon’s Jeri Kelly told me. “The season is so limited to when you can really access things. This is one of the snowiest inhabited places in North America.”

A Northern flicker enjoys the forest at Crater Lake National Park/Jennifer Bain

She likes to begin her Crater Lake sightseeing and hiking tours at the south end of the park by NPS signage that explains that you're standing at the same elevation as the bottom of the lake.

“It’s just kind of amazing to start down here and think about all of the changes,” Kelly told me. “There are 180,000-plus acres in this park, but a lot of people just go up to look at the lake.”

We toured East Rim Drive — literally “the road less traveled” — looking in vain for Clark’s nutcrackers and consoling ourselves with Dr. Seuss-like pasqueflowers, a Northern flicker, a coyote and a black bear cub.

Wizard Island gets all the attention but Crater Lake is also home to the Phantom Ship, a tiny island that is much bigger than it appears from Phantom Ship Overlook/Jennifer Bain

At Cloudcap Overlook, we saw whitebark pines clinging stubbornly to the shallow soil.

At Pumice Castle Overlook, we admired a layer of orange pumice rock that has somehow been eroded into the shape of a medieval castle.

And at Phantom Ship Overlook, we took in views of Crater Lake’s “other island,” which looks like a wee sailboat but is as tall as a 16-storey building.

Explore Southern Oregon's Jeri Kelly shares a secret waterfall along East Rim Drive in Crater Lake National Park/Jennifer Bain

“It’s a little fairy land, right?” said Kelly at a secret roadside waterfall she found when biking the road during the last Ride the Rim event. “You can walk right up to it. It’s just this carpet of moss stuck between all the jagged rocks.”

She saved the Lady of the Woods for last. It’s the unfinished and unsigned work of Dr. Earl Russell Bush who fell in love with the park, “as you do, and wanted to make a lasting tribute.”

The doctor had the park blacksmith make him tools to chisel a woman into a boulder in 1917. “My offering to the forest, my interpretation of its awful stillness and repose, its beauty, fascination, and unseen life” is how he described her.

Guide Jeri Kelly shows off the Lady of the Woods, an unfinished female figure carved into a boulder behind the Steel Visitor Center/Jennifer Bain

That quote comes from the “Lady of the Woods Loop Trail Guide,” published by the Crater Lake Natural History Association. The trail’s other nine stops, behind the Steel Visitor Center, showcase the park headquarters’ rustic architecture, stone structures and landscape.

“To be just sitting back here for 107 years, the Lady of the Woods has seen some things,” Kelly mused. “It’s a part of park history that very few people know about.”

The same can be said for the Old Man. He's the only drifting log in Crater Lake — a 30-foot mountain hemlock that’s floating vertically with three feet exposed above water.

Not everyone is lucky enough to see the Old Man, a mountain hemlock log that floats vertically in Crater Lake/Jeri Kelly

First noticed in the 1896 by lake geologist Joseph Diller, the Old Man is at least 450 years old according to carbon dating. During a 1938 study, he traveled an average of 0.67 miles a day but once made it up to 3.8 miles. Nobody knows why he is upright.

Superstitious types believe the Old Man controls Crater Lake’s weather, like that time in 1988 when researchers tied him up to Wizard Island to keep him safe while they explored the lake bottom in a submersible. Storms immediately blew in and then it snowed in August. “The scientists very quietly (and under cover of night) released the Old Man back into the Lake,” the Park Service reveals, “thus restoring the weather and the Old Man’s freedom.”

It was on that trolley tour to see the Grandmother Tree that I caught wind of the Old Man’s existence. For two days, I searched for him with my zoom lens. I never did spot the wily log, but couldn't help but admire how even dead trees fight to keep calling this mysterious lake home.

Get up at sunrise to see Crater Lake, Wizard Island and maybe even the Old Man without having to battle the crowds/Jennifer Bain

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places