One of the most accessible units of the National Park System has to be Montezuma Castle National Monument, which protects a roughly 1,000-year-old cliff dwelling less than 10 minutes off Interstate 17 in northern Arizona.

Located not quite two hours north of Phoenix, and just 45 minutes south of Flagstaff, the monument is a small gem worth a visit.

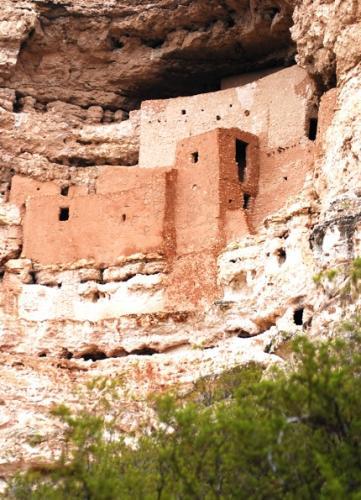

The Southern Sinagua people who built this five-story cliff dwelling chose their location wisely. They tucked their home into an alcove in the cliffside about 100 feet off the valley floor. From there they had protection from the elements, the south-facing dwelling was warmed in winter by the sun, and the height provided a great perspective of the surrounding landscape.

Down below, Beaver Creek provided a reliable source of water, and the fertile soils enabled them to cultivate corn, beans and squash, along with cotton that they turned into thread for weaving clothes. And the sycamore trees that grew along the creek were handy building materials that went into the dwellings.

Archaeologists believe the Sinagua lived here for about four centuries, roughly from 1100 and 1425 A.D. The name -- Montezuma Castle -- was attached to the dwelling in the late 1800s by whites who thought the structure had been built by the Aztec. But there were visitors to the Castle long before whites came along, as Josh Protas writes in A Park Preserved In Stone: A History of Montezuma Castle National Monument:

Antonio de Espejo, following reports of rich mines, entered the Verde Valley in 1583. The Espejo expedition was initially organized to rescue two friars who had remained in New Mexico after the 1581—82 expedition headed by Captain Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado. The company of fifteen men set out from Valle de San Gregorio in Chihuahua, Mexico, and headed north along the Rio Grande to the Pueblo of Pualá in New Mexico, where they discovered that the friars had been murdered. Having a great interest in prospecting and seeking riches, the members of the party decided to explore the country before returning and journeyed from Santa Fe to Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi villages, where they heard rumors of distant mines. The party then split up, and Espejo and four others departed with Hopi guides to investigate the reports of the rich mines to the west. It appears that these travelers were the first Europeans to enter the Verde Valley and describe the features of the region, including its ruins.

Two different records provide information about Espejo's trek to the mines: the journal of Diego Pérez de Luxán, the chronicler of the expedition, and the account Espejo himself wrote shortly after his return from New Mexico. Although there has been debate about the location of the mines and the route traveled, most scholars now believe that the party passed through the Verde Valley to reach mines in the vicinity of Jerome. Luxán's journal of this trip is considered to include an accurate description of the natural features of the Verde Valley and to support the theory of the presence of the expedition in the region. The following passage possibly refers to the Beaver Creek area: "This river we named El Río de las Parras. We found a ranchería belonging to mountain people who fled from us as we could see by the tracks. We saw plants of natural flax similar to that of Spain and numerous prickly pears. We left this place on the seventh of the month and after marching six leagues we reached a cienaguilla which flows into a small water ditch and we came to an abandoned pueblo." The cienaguilla and small water ditch mentioned were probably Montezuma Well and the prehistoric irrigation canal flowing from its outlet. The abandoned pueblo could have been one of the large ruins beside the Well.

The account of the expedition that Espejo wrote later also describes an area with a striking resemblance to the Verde Valley and lends weight to the theory that the Espejo party traveled through the area:

The region where these mines are is for the most part mountainous, as is also the road leading to them. There are some pueblos of mountain Indians, who came forth to receive us in some places, with small crosses on their heads. They gave us some of their food and I presented them with some gifts. Where the mines are located the country is good, having rivers, marshes, and forests; on the banks of the river are many Castillian grapes, walnuts, flax, blackberries, maguey plants, and prickly pears. The Indians of that region plant fields of maize, and have good houses. They told us by signs that behind these mountains at a distance we were unable to understand clearly, flowed a very large river.

Other references in the Espejo and Luxán accounts further substantiate the claim that the expedition journeyed through the Verde Valley. These accounts thus document the first European presence in the valley and their probable encounter with Montezuma Well and its prehistoric ruins. Not overly inspired by the ores found in the mines, however, the small group returned to Zuni to meet the others in their party.

Though relatively small in size, at just more than 1,200 acres, the monument is older than the National Park Service. President Theodore Roosevelt used the Antiquities Act to designate it on December 8, 1906.

What's To See?

The winding road from Interstate 17 takes you down and around a ridge to a narrow parking area, where a short sidewalk leads to the visitor center with a small museum of artifacts and bookstore.

The sidewalk continues on the other side of the visitor center and takes you to some nice vantage points of the "castle," which was home to an estimated 35 people, according to archaeologists. There are some benches where you can sit and ponder the craftsmanship of the Sinagua in building the 20-room dwelling so high off the valley floor.

The difference in color of the dwelling's walls is the result of a replastering of the lower three stories of the structure done in 1996. Continuing past this towering dwelling you'll come to the footprint of "Castle A," which once was a larger dwelling that rose six stories and contained an estimated 45 rooms. Today very little remains of this dwelling, which provided shelter for about 100. Archaeologists say the structure was heavily damaged by a fire in the 1400s shortly before the Sinagua vanished.

The sidewalk offers places to sit, interpretive placards, and a great view of the ruins. Kurt Repanshek photo.

The trail then bends to the left and an overlook of Beaver Creek, and then heads back towards the visitor center. Along the way back you can stop at an exhibit that features a diorama of the castle and an audio tape through which the narrator explains daily life in the dwelling.

Inside the visitor center there's a nice collection of interpretive books and brochures to help you learn more about the monument and the people who once lived here. Some of those materials let you know that the Sinagua were quite sophisticated when it came to trade, as it's thought their reach extended to Mexico, the Gulf of California, and north into Colorado and resulted in their acquisition of copper bells, colorful macaws, and even seashells.

Though it won't take you very long to tour the monument, there are other attractions nearby that can help you fill a day in the area. Just four miles north of Montezuma Castle is Montezuma Well, where you'll find some smaller cliff dwellings and a well that is filled with 1.5 million gallons of water a day. The water runs from this well down into an irrigation ditch, sections of which are thought to date to more than 1,000 years ago.

Tuzigoot National Monument is not quite 20 miles to the west via Arizona 260 and U.S. 89 and features a pueblo the Sinagua built along a ridge. Archaeologists say the structure was two stories high and contained 77 ground-floor rooms.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

The full text of Josh Protas' A Park Preserved In Stone: A History of Montezuma Castle National Monument can be found at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/moca/index.htm for those wanting more information about the history of this national monument.

In addition to visiting Montezuma Castle and Tuzigoot, following historic US Route 89 to the south will take the traveler to Casa Grande Ruin in the Sonoran Desert. Going north on highway 89 there are two more Sinaguan ruins at to visit at Walnut Canyon and Wupatki. Seeing these two along with Montezuma Castle, is a way to understand the diversity of the Sinaguan culture and their prowess as builders of remarkable structures. For a taste of Ancestral Puebloan culture, Navajo National Monument is a short drive east of 89 in northern Arizona. All together, visiting these six National Monuments makes for a fascinating way to explore prehistoric Indian cultures on a two-day road trip. For a driving directions, visit the US Route 89 blog.