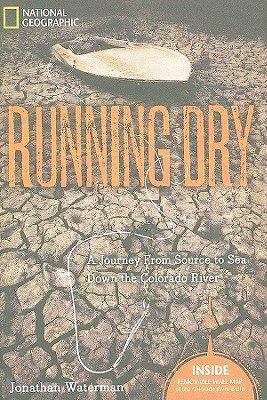

Part travelogue, part warning shot across the bow, Jonathan Waterman in his latest book takes us on a sobering journey down the Colorado River from source to the Sea of Cortez that should scare the wits out of those in the Southwest and convince them to read the dusty writing on the wall.

Major John Wesley Powell warned the government more than a century ago that there wasn't enough water to go around in the West, and Marc Reisner reiterated the message a bit more vehemently in Cadillac Desert, the American West and its Disappearing Water.

Now Mr. Waterman, author of Where Mountains are Nameless, Arctic Crossing, Kayaking the Vermilion Sea, and In the Shadow of Denali, takes his best shot to convince local, state, and federal officials -- and all the souls who live from Colorado and Wyoming to southern California -- that there is no possible way the Colorado River can survive, let alone sustain, the demands being made on it.

From his first step towards the river's headwaters along the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park to his final footsteps "across the scabbed remains of the Colorado River" in the Mexican delta, the author leads us not just down 1,450 miles of iconic river, but points out the too many diversion ditches, dams, and irrigation projects that suck constantly, and increasingly in some areas, from the Colorado.

In the Post-DamNation era, several hundred miles of legendary rapids -- Byers, Gore, Glenwood, Westwater, Cataract, and the Grand -- leave many white-water enthusiasts thinking that the Colorado River is intact. Sadly, it's not. The delta is parched. Upstream, more than 300 miles of river are flooded by reservoirs and blocked by dams. Through a labyrinth of canals and aqueducts attached to these man-made lakes, the 1,450-mile river is diverted to several million acres of farms and 10 percent of the U.S. population. The reservoirs can store more than four times the river's annual flow. Several years before the national recession, the number-crunching water operators of the Colorado River Basin warned that the river's holdings were in danger of being overdrawn, with its customers living on false credit, its habitat on the very of bankruptcy.

This wild river ride that Mr. Waterman takes us on is personal, too. As he was planning his odyssey he watched his mother slowly die of cancer. "I showed her pictures and a map of the Colorado River and told her what I planned to do," he writes. "A month before her death, shortly before she lost the ability to speak, she licked her lips in an attempt to wet her parched mouth and cheerfully conceded that she too was going on a long journey."

Mr. Waterman carried that memory, and his mother's ashes, with him. While he scattered her ashes "into the breezes above the remains of the Colorado River headwaters," he carried her memory with him to the Pacific. That the author freely inserts his family into the story contributes to the points he tries to convey. The home on 20 Colorado acres he shares with his wife, June, and their children, features no thirsty Kentucky bluegrass but rather native wildflowers and forbes. There's a solar system to heat water, a greenhouse to grow vegetables, and ample existing water rights to live comfortably. He contrasts that with the soaring demands placed on the watershed of the Colorado.

One hundred and sixty miles away live two million thirsty Denverites extended straws toward the distant Colorado River. On the surrounding plains, another 1.8 million Coloardoans poke shorter straws to reach one of four Denver Basin acquifers containing paleowater from the last ice age.

In our own small way, compared to the megalopolis, we are trying to retain a balance.

As the story pulls us downstream it diverges into a travel narrative as we're taken through Canyonlands National Park, down fabled Cataract Canyon, into ancient ruins, and schooled not-so-delicately on the proper way to use "groovers" as toilets.

But throughout the text the Colorado runs like a diseased coronary artery through the heart of the book. The author clearly diagnoses the disease by analyzing the math attached to the water that feeds the various watersheds draining into the Colorado, and the over-appropriated demands on them. He talks with the director of the Glen Canyon Dam that reins in the Colorado before it can sweep tumultuously through Grand Canyon National Park, and in doing so contrasts the ongoing stand-off between hydro-generation and the natural ebb and flow of river flows the canyon needs to stay healthy.

Not surprisingly, both Major Powell and Mr. Reisner merit mention by Mr. Waterman, who also serves as historian in painting his portrait of an arid West. But it's his own personal reflections and insights -- and his paddle strokes, whether in kayak or raft -- that propel the book forward.

What remains to be seen, though, is whether readers take his message to heart or simply interpret it as just another river trip.

Comments

Sounds like this Waterman guy is just another of those environmental wackos who just doesn't understand what America is all about. It's simply unAmerican to suggest that we actually conserve or apply real stewardship to the land around us.

Every true American knows the truth: This world and everything in it is OURS! Ours to exploit in whatever fashion may reap the greatest rewards for the richest of us.

Here in Utah, the official state environmental mission statement is "Multiply, multiply and pillage the Earth." C'mon, folks. Get with it and forget this nonsense.

Now I gotta go buy the book . . . .

Many years ago I happened to share the elevator accessing tours of Glen Canyon dam with a federal hydrologist. He claimed that one gallon out of three of Colorado River water entering the reservoir ended up seeping into the sandstones under the Navajo Reservation!

And for years it has been known that in summer heat, six inches of water evaporate from all of Lake Powell's surface. That, they say, is enough to handle all the water needs of Los Angeles for a day. Then, downstream, how much evaporates at Lake Mead and so on?

I've heard, and think it's probably true, that due to evaporation upstream water in the Yuma area is dangerously saline and can cause crop damage.

Legal Strategy:

At all times and places we are to contend that the current law of the river of "prior appropriations" has outlived its usefulness, is obsolete and void. Expressed in another way, the "prior appropriations" law of the river was a form of judicial activism developed in the mid 1800's to encourage the population of the west and that now that this goal has been accomplished "prior appropriations" water laws are no longer useful or appropriate and are void.

Establishment of this "meme" that "prior appropriations" laws are now void will result in automatic renewal of historic "riparian rights" water laws. Voila! All dams, diversions and levees, etc. on the river thereupon become illegal as gross violations of riparian water rights so that all the flows of river water must be allowed to flow past these illegal structures.

Do you remember when the Sierra Club sold its (0urs) soul to the devil when they backed support for the building of Glen Canyon Dam in return for not building two lesser dams in the Northwest? Every story has two sides. Its all about power, greed, and control.