LOGAN PASS, Mont. — In this landscape defined by glaciers, mountain goats

rule. Nimble, decked out with curved black horns, professorial

goatees and thick, woolly coats, these all-terrain animals must also be a

tad egotistical. Why else would they congregate along the Hidden Lake Trail

within sight of the Logan Pass Visitor Center and pose for Glacier National

Park visitors?

Nimble, decked out with curved black horns, professorial

goatees and thick, woolly coats, these all-terrain animals must also be a

tad egotistical. Why else would they congregate along the Hidden Lake Trail

within sight of the Logan Pass Visitor Center and pose for Glacier National

Park visitors?

I am in a small gaggle of tourists busily training our

armament of camera lenses on the goats as they grazed contentedly on the

wildflower-strewn emerald slopes. The goats are so close they could be

models strutting a runway.

Pikas, furry cat-sized rodents obviously jealous

of our focus, keep up their shrill barking to distract us, while towering

overhead are the cirques, glacial horns and snowfields that most often come

to mind when Glacier is mentioned. Nevertheless, we fill our cameras with

goats. There always will be time for scenery, but who knows what schedule

the goats follow?

Not that it matters. There’s no loss in trading scenery

for goats or vice versa in Glacier, a million-acre-plus park in northwestern

Montana nudged up against the Canadian border. Though its glaciers are

retreating — some scientists predict that, with current conditions, they

could be gone by 2030 — their absence won’t make the park any less alluring,

for its pristine lakes and forests and crags and wildlife are a breathtaking

throwback to colonial days.

Designated in 1910, almost two decades after

the Great Northern Railway brought its tracks and trains across the

relatively low 5,220-foot Marias Pass just below Glacier’s southern

boundary, Glacier tosses more ruggedness at you than just about any other

park in the Lower 48. You can see that from atop 6,664-foot Logan Pass.

The Going-to-the-Sun Road climbs up to, across, and down the pass. It’s

narrow, and at times precipitous, in a constant state of repair due to the

ravages of the freeze-thaw cycle. Beginning in 2007, park officials plan to

launch an ambitious rebuilding program intended to gain the upper hand on

both the mountainous terrain and the climate.

Logan Pass, the apex of the

Sun Road, is pinched tightly between Clements Mountain and the southern tip

of the Garden Wall, a massive rib of rock that carries the Continental

Divide through the park’s interior. From this saddle the pass sends Reynolds

Creek and Logan Creek in opposite directions as their waters cascade down

massive U-shaped valleys scooped out during the park’s glaciated past.

Farther north are the bulk of the park’s glaciers — thick sheets of ice

named “Ipasha,” “Old Sun,” “Grinnell,” “Swiftcurrent,” “Thunderbird” and

“Rainbow” — while to the south stands a maze of mountains, valleys, meadows

and backcountry lakes that it would take a lifetime to know.

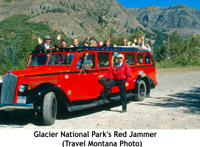

Many park

visitors motor up to the pass aboard a Red Jammer, one of Glacier’s renowned

fire engine-red, open-air touring buses that debuted in 1937 and quickly

gained their nickname for the way drivers “jammed” their way through the

gears. Along the way, they struggle to digest this complex landscape that

the Blackfoot Nation — the park’s original human inhabitants — calls the “Shining Mountains” and the “Backbone of the World.”

Here Bird Woman

Falls spills 492 feet to Logan Creek, over there on the western horizon,

ponderous Heavens Peak shimmers under streaks of its permanent snowfield,

here’s a meadow of Beargrass and Glacier lilies.

Weeping Rock showers

west-bound Jammers with icy snowmelt, while the Highline Trail shuttles

hikers, and the ubiquitous goats, 7.6 miles into the backcountry and the

Granite Park Chalet, a rustic stone-built shelter that’s a throwback to the

1910s when pack horses hauled visitors across the park.

So massive is

the park that it’s both a sin and a miracle that only the Sun Road slices

entirely through the interior. A few shorter roads jog briefly into Glacier,

but they are mainly the domain of locals who want to vanish into the

landscape. Glacier visitors who only negotiate the Sun Road before heading

elsewhere gain just a small sense of the park, with its many lakes and more

than 700 miles of backcountry trails.

So massive is

the park that it’s both a sin and a miracle that only the Sun Road slices

entirely through the interior. A few shorter roads jog briefly into Glacier,

but they are mainly the domain of locals who want to vanish into the

landscape. Glacier visitors who only negotiate the Sun Road before heading

elsewhere gain just a small sense of the park, with its many lakes and more

than 700 miles of backcountry trails.

For them a Red Jammer tour

offers the perfect Glacier sampler, as I discover one sunny mid-summer

morning as we head out from Lake McDonald Lodge. For the next three hours,

Barry Gray, the Jammer’s driver, regales his 17 passengers with Glacier

facts and trivia, pointing out stromatoliths — fossilized blue-green algae

—, the Livingston and Lewis mountain ranges and avalanche chutes that in

springtime double as “grizzly bear frozen food sections” for the carrion of

goats, bighorn sheep and other critters kept on ice until foraging grizzlies

dig them out.

To gain a better feel for the park and its setting, I leave

Lake McDonald Lodge the next day and backtrack to West Glacier, heading east

along U.S. 2 as it meanders along Glacier’s southern boundary. I am

retracing the route the Great Northern trains once followed and which Amtrak

now rumbles along twice daily. Passing the tiny enclave of East Glacier I

continue north to Browning and the Lodgepole Gallery and Tipi Village, where

Darrell Norman, a member of the Blackfoot tribe, provides me with two great

nights of sleep in one of his rental teepees.

“People come here

because they want to know about Native American people,” Norman says to me

and his other guests over a dinner of ground bison, wild rice with

mushrooms, a spicy salsa, cauliflower and broccoli that’s joined by a

middle-of-the-road bottle of red wine.

They can experience what he

calls “Native American tourism” for a night in one of his teepees, and take

it home in the form of some of the jewelry, photography, paintings,

sketches, ceremonial drums and other Native American art he and his

German-born wife, Angelica, and other Native American artists make. Norman

also doubles as a one-man chamber of commerce for the Browning area, the

center of the Blackfoot Reservation. It’s a community that sadly has one of

the highest, if not the highest, unemployment rates in Montana. But it’s

also an area of breathtaking scenery and immense possibility.

Between

Browning and St. Mary, sturdy, two-lane U.S. 89 provides sweeping vistas to

the east of what the vast Indian nation circa 1850 must have looked like.

Rolling steppes of tall grasses, broken occasionally by copses of aspen, run

off toward mid-America. To the west, rise the stone cathedrals of

Glacier.

Once upon a time the eastern half of Glacier was Blackfoot

land. But in 1895 the tribe’s chiefs sold the land so they could buy food

for their starving people. However Norman maintains that what the U.S.

government considered a “sale” was in fact nothing more than a 99-year

lease.

“When they made it a national park, they got amnesia about what

they agreed to in 1895,” claims Norman.

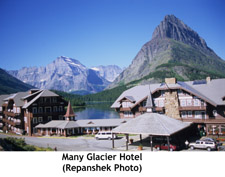

Leaving the dispute behind, I

head to Babb, north of St. Mary, where the simply named “Glacier Route

Three” leads me 12 miles west back into the park to Many Glacier with its

magnificent four-story lodge set along the shore of Swiftcurrent Lake.

Opened in 1915, the Swiss alpine-themed Many Glacier Hotel is ringed by

craggy mountains. Though the rooms are small and cramped, the lodge is a

great base for wilderness forays, day hikes and paddles across the lake.

Leaving the dispute behind, I

head to Babb, north of St. Mary, where the simply named “Glacier Route

Three” leads me 12 miles west back into the park to Many Glacier with its

magnificent four-story lodge set along the shore of Swiftcurrent Lake.

Opened in 1915, the Swiss alpine-themed Many Glacier Hotel is ringed by

craggy mountains. Though the rooms are small and cramped, the lodge is a

great base for wilderness forays, day hikes and paddles across the lake.

Down at the dock, a scenic cruise is ready to embark on a trip across

Swiftcurrent Lake, while a family launches a canoe and kayak into the water.

On the far shore, a bull moose is knee-deep in water, taking his morning

breakfast from the lakebed vegetation. I gaze at the surrounding mountains,

longing to see more of this wondrous landscape. But the rest of Glacier is

too expansive to fully sample in one week. Rather, like a rich chocolate

mousse cake, the park is to be taken a slice at a time and savored.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments