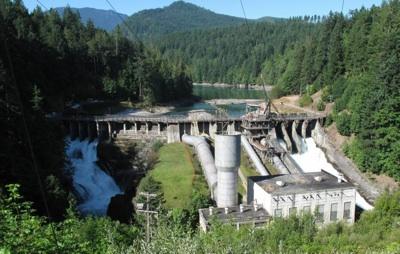

An audit found that the contractor involved in the removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams in Olympic National Park never released the federal government from its contractual obligations/NPS

A random review of contracting practices the National Park Service is supposed to follow but doesn't always manage to shows the agency is missing the opportunity to spend tens of millions of dollars assigned, but not needed, on other projects in the park system.

The review (attached below), by the Interior Department's Office of Inspector General, estimated that the bookkeeping lapses by the Park Service's National Capital Region and Denver Service Center left $52.5 million of available, but unused, funds. The lapses stemmed from the two regions' inadequate oversight of procedures to be followed when a contract is to be closed, failure to prioritize closeout in a contract's life cycle, and a lack of Park Service policies and procedures to ensure contract closeout requirements were met on a timely basis.

The OIG offered the Park Service six recommendations for correcting the problems, and the agency has implemented half of them, with all to be in place by the end of 2018.

One key aspect of closing out a contract is releasing, or "deobligating," funds appropriated for a specific contract but left over after the project has been completed and the contractor paid.

Closing a contract includes tasks such as verifying goods and services were provided and making final payment to the contractor. Contract closeout is important because it enables the U.S. Government to protect its interest against litigation, and releases excess funds tied to the contract by deobligation. Having a large number of contracts awaiting closeout after the FAR’s time standards poses a financial risk to NPS. Generally, the appropriations used to fund a contract cannot be used to incur new obligations after the end of the fiscal year for which it was appropriated. NPS can use the original appropriated funds for additional five fiscal years beyond expiration to adjust and make payments to liquidate liabilities arising from obligations made within fiscal year for which the fund was appropriated.

In its review of 89 contracts with a value of $33.7 million, OIG found that the two regional offices:

- Did not close 76 of the contracts within the required timeframe, with some delays running more than three years;

- Failed to prepare contract closeout statements to verify that required closeout steps had been completed for 64 contracts;

- Failed to complete an initial funds review to identify excess funds for deobligation for 54 contracts;

- Failed to obtain a release of claims for 10 contracts where the release was required;

- Failed to close 74 contracts in the Procurement Information System (PRISM) contract management system that had been completed, and;

- Failed to adequately document 52 contracts.

"These deficiencies occurred because DSC and NCR personnel were unaware of contract closeout requirements or were performing other duties," the auditors concluded. "In addition, DSC and NCR had not implemented processes and procedures that ensure compliance with contract closeout requirements, such as automated closeout statements for contracts that use simplified acquisition procedures and procedures for documenting contract completion milestones."

In the Denver Service Center, staff estimated the number of contracts waiting to be closed was approaching 1,000.

As noted above, there were ten cases where Park Service staff failed to obtain a release of claims; basically a document signed by the contractor stating that they have discharged the government from all liabilities, obligations and claims. Failure to obtain such releases could place the government at risk of future claims and legal issues down the road, the OIG noted.

In one case, the Park Service failed to obtain such a release on a $2.1 million contract for the Flight 93 National Memorial in Pennsylvania, and another one was for a $1.2 million project associated with the removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams in Olympic National Park in Washington state.

Comments

While this doesn't exactly shine the best light on the NPS it is good to see an issue identified and steps being taken to ensure problems like this don't continue. I would like to read more atricles on what the NPS is doing themselves to run more efficiently. I think it is important when you are spending other peoples money to show that every effort is being made to spend that money wisely and efficiently. The same goes for EVERY governmental department including the OIG itself.

My question is where did those funds go? A project gets funded, they don't spend all the money, the additional funds don't get "deobligated". Is the cash sitting at the park or NPS headquarters or is it being spent on unathorized programs or being put in some employees' pocket. Makes a big difference. If in the first two then it seems this is not much more than a book keeping issue. If the later then .......

Since you read the headline and not the article, the unused funds can still be used within five years for certain purposes. Otherwise, it's like the money ceased to exist - their electronic account is simply closed. This is waste because the contracts need to be closed too and only real estate people get away with stiffing contractors. So a pile of money is effectively set on fire and while bills still need to be paid.

This is wasteful and might be alleviated if more carryover were allowed but the fundamental problem is a mixture of incompetence and overwork (guarantee these 89 contracts are overseen by way fewer people than in the private sector who also don't usually have equivalent training or experience).

Unlike the private sector, feather-bedding is pretty obvious, so the idea of this going to some employee's pocket says more about your business practices (again) than the federal government's.

Toxie, contrary to your accusation, I did in fact read the article. It would appear the five years you mentioned applies to liabilities of the original project not some unlimited capacity to spend the money on other projects.

Please explain how money "ceases to exist'? Either it never existed (wasn't paid out of the treasury) or it was paid to someone, the DOI, the NPS, a park.... and all wasn't spent on the intended project. If the former, its a book keeping issue, if the later, it would be nice to know where the moeny went.

It goes nowhere. Taxes were collected (and debt issued), funds were appropriated and then were not and, because of law, never will be spent. Any of the the other purposes you suggest would have been in such an OIG report because they are either insanely illegal (fraud) or against regulations (abuse). You will note that they they are not mentioned.

Since it's all electronic, maybe it's more like physical money being locked into a safe and tossed into bottom of the Marianas Trench. Either burned or drowned, it is taken out of the money supply.

Business majors are pretty bad at real Econ but reducing the money supply should be avoided. In addition to it being government waste.

And if they never left the treasury it is nothing but a bookkeeping issue. Has nothing to do with Econ.

The National Park Service has long been an agency where lobbying for more money is a far higher priority than accounting for how the last batch was spent. This seemed true of operations and maintenance spending as well as contracts. Toward the end of my career I was appointed acting Trail Foreman for a month as a training exercise and learned far more than I suspect was intended.

One of my main tasks was to prepare a 'Completion Report' on an in-house six-figure trail bridge replacement. My supervisor's desk drawer had more unfiled CYA leave slips than the incomplete scattering of project purchase receipts I found. The park Chief of Maintenance was quite upset when I told him I didn't have enough information to do the job. I got the definite impression that he expected me to fake it. Almost as troubling was that it seemed SOP not to include park wages (probably at least $50K, but not documented) as a project cost, since "that was already paid for."