As spectacular as sunsets can be at Everglades National Park, they can't hide the nearly $100 million in maintenance backlog needs at the park/NPS

Some of the world’s greatest wonders exist in America’s National Park System, from the Grand Canyon and Old Faithful to Mammoth Cave and the Everglades.

But the system also features ailing wastewater treatment facilities, rotting buildings, and even the risk of demolition by neglect. Many parking lots are crumbling, some communications systems are antiquated, dams and levees are in serious condition, and employee housing in some parks is shabby.

And the list goes on and on. Open an Excel spreadsheet of the National Park Service’s estimated $11.6 billion maintenance backlog and it runs to thousands of lines of data. But those lines are just one aspect of coming to terms with the impacts of the backlog. Get out into the National Park System and the impacts become readily visible:

* Travel the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina and stop at the much-loved and historically significant Bluffs Lodge at Milepost 241.1 and you’ll find not only a building that the Park Service in 2005 said “must be preserved and maintained,” but one that today is shut down, shuttered, and filled with dangerous, creeping molds that have placed the building off limits to all.

* Visit Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico later this year and you might be able to ride one of the two primary elevators down more than 700 feet into the cave, a ride not possible since November 2015 when the then-60-year-old elevator sheared its 6-inch motor shaft. But if it’s not fixed by Memorial Day as the Park Service hopes, you’ll have to walk the steep ramp down into the cave because the two backup elevators failed last month.

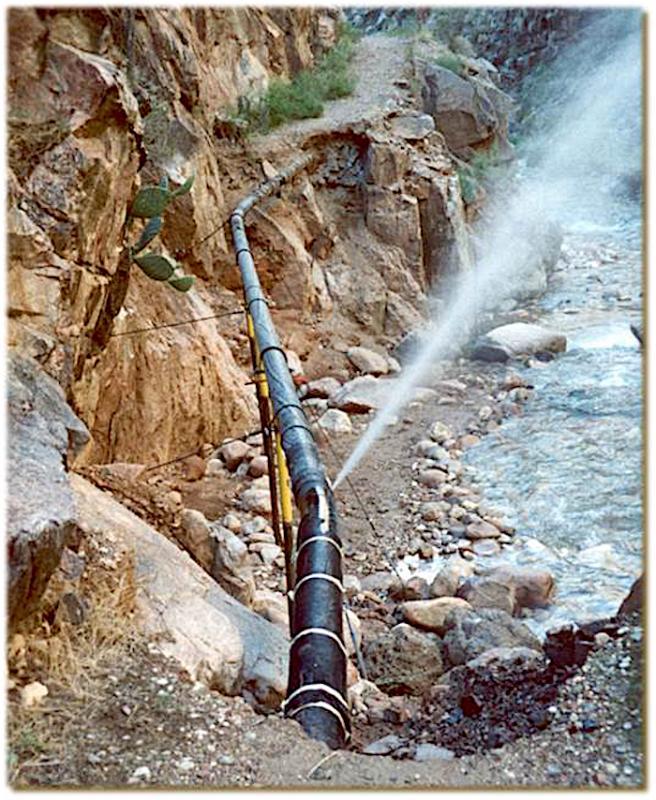

* Grand Canyon National Park crews keep their 53-year-old Transcanyon Waterline operating with the proverbial baling wire and duct tape. The frequent, and costly, breaks in the pipeline that brings water to the South Rim from Roaring Springs on the North Rim create not only an inconvenience but also pose a health and safety issue for those on the South Rim.

One of the single-biggest maintenance items, in terms of dollars, in the National Park System is the need to replace the Transcanyon Waterline at Grand Canyon National Park, where replacement costs have been estimated at $100+ million/NPS

The stories go on, from some historic trails in Acadia National Park in Maine closed to the public because the park lacks the nearly $10 million needed to repair them to an ailing wastewater treatment system at Arkansas Post National Memorial in Arkansas that requires half-a-million-dollars in repairs. And there's $11 million needed at Cape Hatteras National Seashore on North Carolina’s Outer Banks to address building maintenance deemed “critical” or “serious.”

“Deferred maintenance affects parks of all size and type,” said Park Service spokesman Jeffrey Olson. “Small parks may have more difficulty in addressing needs since those parks may not have access to resources such as recreation fee revenue or local friends groups or volunteers.”

To his point, at Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve in Florida the 2017 backlog was pegged at $3,852,352. Part of that total, said Mr. Olson, relates to “plans to rehabilitate Fort Caroline Visitor Center walkways.”

Since George W. Bush pledged in 2001 to wipe out in five years the Park Service’s maintenance backlog, then estimated at $4.9 billion, the sum has steadily grown no matter how much attention was focused on it. By 2013 it had reached $11.3 billion. It peaked at $11.9 billion in 2015, and today resides somewhere a bit north or south of $11.6 billion. Just more than half ($6.1 billion, when you consider paved and unpaved roads, bridges, tunnels, and parking lots) of that total is directly related to roads. Trail needs are estimated at $462.2 million. Campgrounds contribute nearly $76 million to the total. Building needs are tabbed at $2 billion.

Of that $11.6 billion total, $2.6 billion of the needs are considered “critical or serious maintenance located in critical asset components” by the National Park Service. However, that figure does not include critical needs for paved roads in the park system, as that category for roads hasn't been calculated, according to NPS documents.

Those dollar figures are somewhat soft, always moving as old projects get completed while others grow direr, and accounting checks fix math errors.

Some groups place part of the burden on concessionaires in the park system. The Center for American Progress, a progressive public policy research center, in 2017 claimed that those private companies that operate lodges and restaurants in the park system should cover nearly $400 million of the backlog related to those facilities.

“Congress should focus its infrastructure and maintenance investments on helping the National Park Service protect the natural and cultural resources in our parks, and force for-profit companies in the parks to pay their fair share for upkeep,” Nicole Gentile, the group’s deputy director, said at the time.

“Because concessionaires – rather than U.S. taxpayers – profit from these businesses, the concessionaires should be on the hook for these kinds of maintenance projects. In fact, the contracts already stipulate that concessionaires are responsible for this maintenance, therefore including these costs in the maintenance backlog is misleading at best and a misuse of taxpayer dollars at worst,” the group said after analyzing the backlog numbers.

Park Service officials, however, say those costs are included in the total because taxpayers are ultimately responsible for them if a contractor does not pay to maintain a facility.

Not only is the Bluffs Lodge along the Blue Ridge Parkway not open to guests, but it's closed to everyone due to dangerous levels of mold inside the building/David and Kay Scott

Congress, which holds these lands in trust for the American public, always seems willing to pass legislation adding units to the National Park System, but isn’t as quick to pay for their upkeep. According to Deny Galvin, a former deputy director of the National Park Service, not since the Mission 66 campaign that ran from 1956 to 1966 and saw $1 billion invested in the park system’s infrastructure has the Park Service seen a significant increase in funding for infrastructure needs.

"Through Mission 66, a billion dollars was spent in ten years. Most of those projects, including over 120 visitor centers, are still serving the American public," Mr. Galvin testified before a congressional committee a year ago. "There has been no comprehensive infrastructure effort since the end of that program in 1966. Most park facilities are, thus, over 50 years old."

It was about the same time in 2017 when U.S. Sens. Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat, and Rob Portman, an Ohio Republican, introduced their National Park Service Legacy Act, a 30-year plan to address the backlog. It would use congressional appropriations to address the backlog. But as of Friday it had just 19 Senate cosponsors. Over in the House, 71 of the 435 members had affixed their names to it.

Also in 2017, U.S. Rep. Michael Simpson, R-Idaho, introduced the "LAND Act," which calls for extending the life of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which provides revenues to be spent on "natural areas, water resources and cultural heritage, and to provide recreation opportunities," through Fiscal 2024. The measure also would create a "fund in the Treasury for the deposit through FY2024 of $450 million from mineral revenues that are not otherwise credited, covered, or deposited under federal law. Of amounts made available from this fund, the Department of the Interior shall use specified amounts for high priority deferred maintenance needs that support critical infrastructure and visitor services."

Earlier this year saw introduction of the National Park Restoration Act, the de facto Trump administration proposal to create a fund of up to $18 billion from royalty revenues derived from on- and offshore energy development to pay for maintenance. It has drawn criticism from some for relying on energy development on public lands to pay for shrinking the backlog. The legislation was sponsored in the Senate by Lamar Alexander, a Tennessee Republican, and in the House by Rep. Simpson.

While Sen. Alexander also is a cosponsor of the Portman-Warner bill, the Trump administration does not support it. That prompted the senator to work with Rep. Simpson to craft legislation that would mirror the Trump administration's approach to paying for maintenance in the parks. The senator views it as a better vehicle in that it provides an automatic revenue stream that would come on top of the Park Service's annual appropriation from Congress. However, the revenue stream could ebb and flow in lockstep with royalty revenues.

Senate Democrats offer their own "Jobs and Infrastructure Plan for America's Workers" that would earmark $15 billion to address backlogged maintenance projects across all public lands, with $5 billion specifically dedicated to "the highest priority deferred maintenance needs at the National Park Service."

So bad is corrosion to the Arlington Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C., that the National Park Service said in 2016 that it would close the bridge by 2021 if it was not repaired. Last December a plan to make the repairs was announced by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke/NPS

Back in 2016, the year when the National Park Service celebrated its centennial, U.S. Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva, D-Arizona, called for Congress to appropriate an additional $300 million per year for fiscal years 2017, 2018, and 2019 to help the Park Service deal with the maintenance backlog. But U.S. Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, wouldn't consider the measure.

Marcia Argust, who leads an effort by The Pew Charitable Trusts to see "long-term solutions" implemented to erase the maintenance backlog, cites the recent efforts in Congress as proof that the upwelling of public interest in seeing the backlog addressed is making headway with the politicians.

"I think the recent increase in the allocations in the omnibus (funding) bill for the deferred maintenance accounts (an additional $160 million) is another good sign that the message is getting through to Congress, folks are paying attention to this issue," she said. "Many different voices are calling on Congress to dedicate more resources to park maintenance. Over 3,000 organizations to date, and local officials, have called on Congress to dedicate resources to park maintenance. I think that message is getting through.”

While philanthropy remains vital – David Rubenstein alone has donated tens of millions of dollars to rehabilitate such icons as the Washington Monument ($7.5 million), the Lincoln Memorial ($18.5 million), and the Arlington House ($12.35 million), among others – it plays a small role in tackling the backlog. At the same time, national park friends groups, which once took pride on providing a “margin of excellence” for their parks, are now being asked to do major surgery on muscle and bone in the system.

In the coming months, National Parks Traveler will take a closer look at the maintenance backlog across the park system. Specifically, we’ll be reporting on how it impacts health and safety, historic properties, infrastructure, and visitor experience, among other issues.

You, the park travelers, can contribute to these stories by pointing out problems you find in the park system that are related to this backlog.

Support for this reporting was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Comments

Outstanding article that looks at the many facets of the issue. I look forward to your continued look at this issue. Thank you !

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm

Had to go really bad, went from stage 1 @ the entrance station of Sequoia NP last week to stage 3 in a hurry, it was touch and go if i'd make it the Ash Mountain visitors center, and luck was on my side as I practically ran to the bathroom, which had 1 toilet and a large Glad bag over the 1 urnial.

We get about 2 million visitors to Sequoia NP, half of which are male, so 1 toilet for a million men!