Big Spring Lodge, Ozark National Scenic Riverways/NPS

Craftsmanship flowed through the main building and surrounding cabins the Civilian Conservation Corps built above the Current River in the hill country of southeastern Missouri. But the passage of nearly nine decades has taken a toll on the Big Spring Lodge and Cabins at today's Ozark National Scenic Riverways, where the National Park Service shuttered the buildings four years ago until they could be rehabilitated.

At Death Valley National Park, Scotty's Castle has been closed the past three years, and likely won't fully open to the public before 2020, due to flood damage that requires extensive repairs and upgrades that have pushed the bill towards $50 million. The Sugarlands headquarters for Great Smoky Mountains National Park needs extensive rehabilitation, at an estimated cost of $5 million. Since 2010, the Bluffs Lodge at the Blue Ridge Parkway has been closed due to lack of a concessionaire, and during the past eight years a dangerous black mold has coated much of the interior.

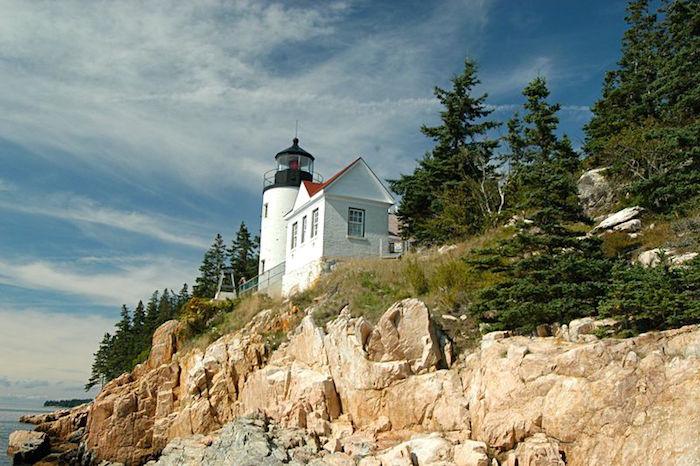

These are just some of the most glaring examples of where, across the National Park System, a lack of funding has crippled facilities used by both the National Park Service staff and visitors. New examples crop up every year. At Acadia National Park in Maine, for example, the U.S. Coast Guard's decision to transfer the Bass Harbor Light and supporting buildings to the Park Service is expected to add to that park's deferred maintenance bill.

Unknown maintenance costs are accompanying Bass Harbor Light to Acadia National Park/Wikimedia Commons, Lorax

“I believe that, technically, that building is not considered deferred maintenance until it comes into Park Service ownership, but the day it does then it will add to that tally," said David MacDonald, president and CEO of Friends of Acadia, the nonprofit organization that supports the park where it can. "The lighthouse is currently owned by the Coast Guard, the Department of Homeland Security. So it’s going to be a transfer without consideration from one government agency to another. And when the Coast Guard let the Park Service know a few months ago that they were ready to decommission this, the Park Service frankly hesitated (to accept the transfer) because of the (deferred maintenance) backlog they’ve got throughout their existing holdings. They had to ask themselves, ‘Gee, is it responsible to add another tract, particularly one that has historic structures in need of repair?’"

While legislation is moving through Congress that would provide $6.5 billion over a five-year period for the Park Service to address such maintenance work, that would cover only a bit more than half of the current estimated backlog of nearly $12 billion. That figure has been growing steadily from year to year, both due to lack of necessary funding and to new maintenance projects being dubbed deferred. Under the Park Service's approach to bookkeeping, once a maintenance project becomes more than a year old, it falls into the deferred maintenance category.

Lack of adequate funding from Congress not only can slow down the Park Service's pace of clearing maintenance projects, but it can keep projects, such as that involving the Big Spring Lodge and Cabins at Ozark National Scenic Riverways, from moving forward. While the facilities were closed in 2014, the restoration work on the buildings isn't expected to begin before 2020.

Much-needed upgrades and repairs to Big Spring Lodge at Ozark National Scenic Riverways have been delayed by a lack of funding/NPS archives

“We’ve sort of just been bumped back in the schedule a couple of times," said Dena Matteson, the park's chief of interpretation, planning, and partnerships.

The Park Service's budget analysts in Washington "sort of tentatively set a project work list, but then those things adjust, even annually, as bigger priorities or disasters or whatever, as funding is moved to other areas or whatever might be," she explained. "We initially expected the project to move forward by now. And then the flood last year also contributed, because the utilities then were delayed a little bit, starting, because of the flooding in that area, into the lodge.”

The work planned for the lodge and 15 outlying cabins is substantial. Electric utility lines are scheduled to be replaced and placed underground, water and sewer lines are to be replaced, and the structures are to be upgraded to make them comfortable for a longer season beyond what had been three-season use, said Matteson.

“They’ve typically been open kind of a three-season situation because the climate control in them has not been that great," she said. "The heating option up until now was just fireplaces, so they typically weren’t used at all through the wintertime, because there wasn’t a good option to heat them. We hope that through this restoration it’ll give the concessionaire an opportunity to keep them rentable year-round and really grow the shoulder season business more than it has been.”

Some rock work done by the CCC crews also needs to be repaired, she added, as does some of the woodwork from that era.

Of course, Ozark National Scenic Riverways isn't the only unit of the park system that has structures created by the CCC as much as 85 years ago. At Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and Tennessee, the 75-year-old headquarters building built by the crews has aged fairly well, but still has some maintenance issues that come with the years.

Handsome from a distance, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park headquarters building has some significant maintenance needs, including a new HVAC system to replace the 75-year-old boiler system/NPS

"Structurally it’s sound. However, a lot of the systems that the occupant is dependent on is where it would have exceeded its life cycle," said Alan Sumeriski, the park's chief of facility management.

While the building, which has room for 60-65 staff, is handsome from the outside, the wood furring strips sandwiched between the slate shingles and concrete panels that are the roof have deteriorated to the point of replacement, he said. That's just one element tagged to the roughly $5 million deferred maintenance price tag attached to the building.

“The boiler system is original to the building," Chief Sumeriski said. "And in the '60s and '70s there were some attempts to bring in air-conditioning. And it was done while the facility was occupied, so there’s external components that are exposed, and out of the wall chases, and it really was not sized properly and for that reason, that’s a significant component or element to the rehabilitation of the facility. ... We have continual failures with the HVAC system. It’s not just the boiler, it’s all the plumbing in the walls. That black iron pipe, it’s corroding from the inside out due to the acidity of water and things like that. It’s almost once every six months we’ll have a steam pipe failure. So that’s another major reason for the rehabilitation.”

Architectural and engineering design work for the rehabilitation should be starting in the coming months.

"After 75 years, it’s worth retreading the tires, if you will, vs. razing this building. There are a number of Park Service headquarters buildings across the agency that are very similar to this one, which was constructed at the infancy of the park and requires some significant component renewal. Yosemite, Yellowstone, Olympic. Dealing with this building, I wouldn’t put it on the same plane as the Washington Monument, but it’s really unique to the Federalist period, the design, and unique to the creation of this park.” -- Alan Sumeriski, chief of facility management at Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

At Death Valley, which at the end of Fiscal 2017 had a deferred maintenance tab of $139 million, a driving issue in the delay in repairing Scotty's Castle has been the extent of damage caused by the October 2015 flood and the underlying problems it brought to the surface.

"I say, 'Ah, we’re finally breaking ground,' and you say it’s three years later," said Abby Wines, the park's management assistant. "Yes, but I think generally what the public doesn’t understand is the scale of what happened at Scotty’s Castle. And all the things we need to take care of the site and do it right.”

Flood debris and damage at Scotty's Castle from the October 2015 storm brought to light more than a few problems that needed to be addressed/NPS

With Scotty's Castle listed on the National Register of Historic Places, repairs have to follow restoration guidelines contained within Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. Too, as inspections following the flooding turned up other issues that existed prior to the disaster, they had to be tackled during the repair work as well, she said.

"There are definitely a lot of checkpoints that we go through internally where that very question is asked," Wines replied when I asked about concerns that adjusters might base their estimates on unnecessary, but appreciated, upgrades. "So it’s a lot easier to get funding to repair something that’s broken, or just aged out of being effective, than it is to build a new facility or to replace something with a new facility. That’s always a lot harder to justify. So there’s lots of questions through the funding process where that gets looked at and scrutinized.

"On the other hand, you don’t repair something to broken," she stressed. "At Scotty’s Castle, think about something like the water system. The water line before the flood happened had ongoing leaks that were issues. Then the entire pipeline washed away. It doesn’t exist anymore. Obviously, in that case we’re going to replace it with something new. The thing that used to exist doesn’t exist any more. And it's going to work well. That’s great. We’re not repairing to broken. That would not make sense.”

Further complicating the process with projects, and impacting the cost to the Park Service, are construction costs that always seem to go up, not down. At Ozark National Scenic Riverways, for instance, the actual cost of the repair and rehabilitation work won't be known until the projects are put out for bid.

"Our facility folks’ projections may or may not be right on target as far as the project might actually cost once they get through the architectural design and planning process," said Matteson, whose park had a $47.5 million maintenance backlog at the end of Fiscal Year 2017

And then there are unknown costs the Park Service inherits.

"There was some back and forth as I understand it within the Park Service about whether to take it on or not, even though the parcel is within the congressional approved boundary (of Acadia)," MacDonald said of the Bass Harbor Light transfer. "Basically, Congress has mandated the park to acquire these parcels when they become available. There’s this list of acquisition tracts that are deemed important to complete and round out the park. So it is one of those parcels, that when Acadia’s boundary was passed in ’86, Congress said, 'You should acquire this.'

"It’s an iconic structure, and the park managers, (Superintendent) Kevin Schneider and his team said, ‘This would be a fantastic addition to the visitor experience and the history and we’ve got to take it.’ At the same time, there’s no budget for it," said MacDonald. “They don’t plan for acquisitions like this, and as you know, they really don’t have the ability to keep up with what they’ve got."

To help Acadia, which had nearly $60 million in deferred maintenance at the end of FY17, move ahead with the transfer, Friends of Acadia has raised almost $300,000 "that will help the Park Service cover some of those upfront costs in terms of resource assessments and initial repairs, and allow them to hit the ground running with the property and not have it 'back-burnered'," he said. "We are not anxious to take this on in perpetuity, and not let the Park Service off the hook entirely, but we thought it was an important opportunity not to be missed and to get off on the right foot."

While these projects move along, bumps in the road and all, visitors wait for their completion.

"We have folks that are kind of patiently or impatiently waiting for us to have that project finished, because a lot of folks really have that traditional tie to coming back year after year and using those (cabins)," said Matteson. "So while it’s not a huge occupancy for us, they’re still very popular and stay booked solid just because they have a clientele that returns each year. Folks that are coming through, looking for a cabin while there are still private cabin options in the area, those have that historic draw that really make them the most appealing, and so folks are really, really interested in us getting that wrapped up.”

Support for this reporting was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts

Previous articles in this series:

Traveler Special Report: Closing The National Park System's Maintenance Backlog

Traveler Special Report: Some Friends Groups Asked To Provide "Margin Of Survival"

Traveler Special Report: Maintenance Woes Blocking Access To Parts Of National Park System

Traveler Special Report: Historic Sites And Structures Affected By Maintenance Backlog

Traveler Special Report: Antiquated Wastewater, Sewer Facilities Go Wanting In National Parks

Traveler Special Report: Backlog Of Maintenance Needs Creates Park Risks

Traveler Special Report: Maintenance Backlog Crippling To National Park Roads And Bridges

Traveler Special Report: Private Philanthropy Fills The Gaps Of Deferred Maintenance

Traveler Special Report: NPS Is Running $670 Million Behind On Caring For Maintained Landscapes

Traveler Special Report: Optimism Growing That Congress Will Fund National Park Maintenance

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Thanks for NPT's continued look at this issue.

I don't believe the NPS should take on any new properties unless there is a viable financial analysis that inidcates the facility can either be supported through exsting park budgets or an an alternative approach is agreed to by others (leasing or a concession, for example). Once parks are in the system you consistently see individual and piecemal facility decisions made at a park by park level without adequeate oversight at the regional/DC level - this continues to hurt the agency. In many ways we need a new model for new units coming on board or inheriting new properties. I think many new additions are oversold on old models - if you build it - or designate it an NPS unit - they will come. It isn't sustainable.

We continue to see headlines of overcrowding at big parks out West but many NPS historic sites are losing visitation and have continued to lose visitation overall since the 1990's - yet the NPS at these sites still run full year operations even though the visitation doesn't demand it at all. NPS units can free up some of those operational dollars at the park level to put a new roof on a building, repair a trail, buy a new boilder, etc. Yes, it might mean one less full time interpretive ranger but it might be better to invest in the tangible history to keep it standing. These types of decisions can be made at a Superintendent level and yet the base operations budgets are rarely questioned, if at all. The Ozarks example in this story seems to indicate the NPS is putting all the dollars up for rehabiltation without a new concessioner even in place - that doesn't seem to make business sense, does it? Philanthropy may fill the gap at some places but in many places it won't. NPS doesn't operate like a park system - it operates more like a confederation.

Let's hope if the Parks bill passes this issue of deferred maintenance s tackled in a systematic way and not park by park - that hasn't worked in the past. It is partly what got us where we are. We need a new investment model.

The bottom line is that we have too many parks and can not support all of them. We need to consider shedding some parks and turning them over to state and local governments.

Excellent article and research but it is Big Spring near Van Buren, MO--only one huge spring.

Great catch, Janeann. Should be corrected now.

National Forest maintenance shortfall is far more acute than that of National Parks. In many areas where Forests adjoin Parks, this has resulted in loss of road and trail access to Parks, and of campgrounds surrounding Parks. Alas, USFS has not had the benefit of the degree of political support NPS has, nor does it have the entrance fee revenues Parks collect to support visitor services.

Do you have recent figures for the Forest Service backlog, Rod? I found an FY16 total of $5.5 billion, or less than half of that faced by the Park Service.