The Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act placed 32,261 acres of BLM land in Oregon (50.4 square miles), worth an estimated $161 million, into trust for the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, and the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians/BLM

If we’re not careful, noted the historian T. H. Watkins, we could talk ourselves out of the public lands entirely—even the national parks.

“Perhaps the most consistent losers in the lottery known as the American Dream have been the country’s first immigrants—the Indians. The long sorry tale of the culture clash that turned their world upside down is too familiar to go into any detail here, save to remark that it seems a minor miracle that any Indians at all remain.”

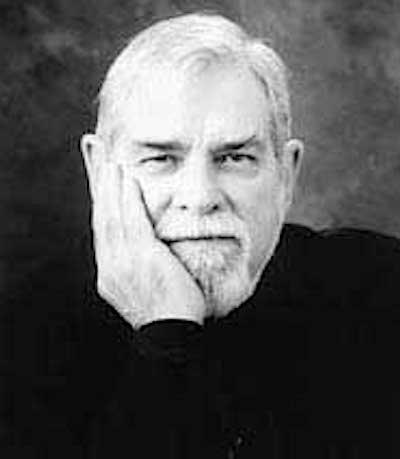

With these words, the historian and editor T. H. Watkins (Thomas Henry Watkins, 1936-2000) plunged headfirst into the minefield of Native American history. The date was September 1974 and his plunge was “Ancient Wrongs and Public Rights,” an essay all the more noteworthy considering its publisher, the venerable Sierra Club Bulletin.

“Forged in necessity and fed by confusion, the official Indian policy in the United States remains an amalgam of guilt, greed, promises, broken promises, and a desperate inability to reconcile the forces of history and conscience,” Watkins observed. Still the key words in that sentence are “forged in necessity,” his subtle but critical reminder that the history could not be changed.

Regardless, by 1974 a growing number of revisionist historians were attempting to do exactly that—change history. I was myself a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, writing my dissertation on the national parks. I admired Watkins for challenging an assertion fast becoming dogma in my own department. Where would the assertion lead, I also wondered, if increasingly taught as gospel?

It would lead, Watkins made the chilling prediction, to the loss of our public lands. Hence his article, and hence the Sierra Club’s determination to see it published. But a few years earlier, in the mid 1960s, the club had nearly lost Grand Canyon, targeted by the Bureau of Reclamation for two high dams and reservoirs. The club felt it had in fact lost the battle for Redwood National Park, ultimately established in 1968 as a hodgepodge of disjointed parcels instead of an entire watershed in Redwood Creek.

Meanwhile, Native American tribes were picking at the boundaries of Grand Canyon and other parks. It was a recipe for disaster, the club believed, especially if big corporations—hiding behind the mask of Indian rights—gained access to the timber and resources.

That Old Thing?

In 1997, during a reception at a parks conference in Bozeman, Montana, Mr. Watkins and I finally met. He praised my books and I praised his. Suddenly, having interjected a compliment about his article, I watched the blood drain from his face.

“That old thing? You mean my ancient history? Don’t tell me you’re still using that!” I admitted I was—and how much I still admired it. It sums up the problem brilliantly, I said. “Perhaps, but there are two sides to everything,” he replied, his voice sinking into a whisper. Just as abruptly, indeed before I could say another word, he had spun around and walked away.

In succession the editor of American West, American Heritage, and Living Wilderness magazines, T. H. Watkins rose to national prominence with Righteous Pilgrim, his 1990 biography of FDR’s Interior Secretary Harold Ickes. In 1997 Watkins accepted the Wallace Stegner Distinguished Chair of Western American Studies at Montana State University, holding it until his death from cancer three years later. Said his obituary in The New York Times: “As a writer on the environment he earned the reputation, like Stegner and Edward Abbey, of one who accepted the might and spiritual tug of nature as factual rather than dreamy and who consequently sought to convey those qualities with literary force but without sentimentality.”

But of course, I calmed myself, still mildly in a state of shock. We were on the campus of Montana State University. By 1997, few universities—even in Montana—welcomed historians on the “wrong side” of American history. Obviously Mr. Watkins, having just accepted the Wallace Stegner Distinguished Chair at Montana State, worried that someone might overhear. In that case, he would spend the rest of his life apologizing for, as he said, his “ancient history.”

I sympathized, but still expected a glimmer of pride from the historian who had dared expose this abuse of history. Why should living Americans be blamed for events—or outcomes—so obviously concluded before they were born?

Because (and further to explain why censorship on college campuses has only gotten worse) the distinction has been rejected. The so-called abuses of history fall on the living; if anything, the living are guiltier than the dead. After all, we are the ones taking advantage of our privileged births by refusing to correct the history.

Correct it how, Watkins asked? None of our ancestors had been “saints.” There had been warfare and dispossession in North America centuries before Columbus landed. Native Americans were just as competitive with one another—and brutal towards one another—when it came to protecting resources and territory.

In short, if compensation in 1974 was the proper policy, why limit it to people of European descent? For example, Watkins asked: “If the descendants of nineteenth-century white Americans have a moral obligation to the descendants of nineteenth-century Navajos, do not the Navajos have a similar obligation to the descendents of the Pueblo Indians, whom they forced from their lands in the thirteenth century? If white Americans have a moral obligation to the Chippewas (or Ojibways), do not the Chippewas have a moral obligation to the Lakota Sioux, whose lands they appropriated by warfare in the seventeenth century? If white Americans have a moral obligation to the Blackfeet, do not the Blackfeet have a moral obligation to the Shoshoni, who were driven out of their hunting territory by the Blackfeet in the seventeenth century? If white Americans have a moral obligation to the Cherokees, do not the Cherokees have a moral obligation to the Shawnees, whom they vanquished in the early nineteenth century in a war over which tribe would have a monopoly selling Indian slaves to the South?”

Critical Theory

Too honest? Too revealing? The point is that honesty once imbued professional history. But again, the tenor of textbooks had begun to change. The revisions were themselves traceable to the rise of so-called critical theory. In critical theory, which is Marxist, unwanted meanings—indeed meaning itself—may be dismissed out of hand as oppressive. Put another way, anything claimed to have meaning is flawed by the mind (prejudice) of the claimant. No matter what you may call supporting evidence, every fact loses its “objectivity” the moment anyone thinks to use it.

Intuition is more important than inquiry; how one “feels” more important than what one “knows.” Are the national parks America’s “best idea?” Only in your mind.

Among Native Americans, pre-Columbian warfare and territorial ambitions could finally be explained by critical theory. What Eurocentric historians had seen as conquest the natives themselves had seen as ritual. Natives seemingly dispossessed by other natives had not actually been dispossessed because, if choosing to reclaim those lands, they need only reverse the ritual.

Historians counting the bodies had gotten it wrong. Besides, any bodies were entirely Europe’s fault, led by the introduction of measles, smallpox, and other diseases into native populations with no immunity.

The upshot, Watkins agonized, was a profession reshaped by expedience. The teaching of history, now fully weaponized, had itself become a threat to the public lands. “Morality is a notoriously tricky proposition,” he countered, still hoping the facts would matter, “and if we even concede that Indians have a legal claim on compensation for lands appropriated by white society, it does not necessarily follow that they have a moral claim on the land itself—land that now belongs to all Americans.”

Fast forward 45 years to the present day. Do “all Americans” still believe that? No, and even environmentalists don’t believe it. These days, the Sierra Club Bulletin, now Sierra, would never publish T. H. Watkins. Environmental editors commonly practice critical theory—even if they don’t know the term.

After all, their college (and political) educations have been steeped in critical theory. When losing an argument, repudiate your opponent’s right to argue. I am not wrong because your facts could never be right, and besides, your facts are meant to oppress me.

As Watkins noted, everything about holding onto our public lands depends on incontrovertible boundaries of agreement—facts. Beginning in 1935 and the close of the public domain, the nation charged itself with keeping the leftovers public, now to hold them for posterity. If later rediscovered to be essential for commercial uses, in all cases they should still be leased.

Such was the pact—and indeed the purpose—of our parks, forests, wildlife refuges, grazing lands, and wilderness. No matter who occupies the land—or claims the right to use it—from now on we keep it public. After all, it is the last common land we will ever have.

The natives of North America had 400 years to defend their system—and in the end could not compete. Why? Because their system, based on exchange, lacked the divisions of labor required to hold their territory. Only if they had jumped at the chance to manufacture guns—not just trade for guns—would Europe have lost its edge. However, unlike the Chinese today natives copied very little. Europe’s intellectual property was safe with them.

Yes, native populations were highly susceptible to disease—and their mortality rates truly dreadful. However, that by itself again does not explain why Europe gained a foothold in North America. A good number of native populations did recover as they built up immunity, too.

Simply put, to keep pigeonholing them as victims throughout the entire period is about as false as the history gets. Many had been and remained military powerhouses, as witness the Iroquois, whose five nations—and then six—sent chills up and down the spines of the Dutch, French, and English.

Native Americans didn’t lose North America overnight. After Jamestown (1607), the Iroquois alone held what is now New York State for another 175 years.

No matter, most in higher education now feel obligated to take a page from the revisionists. The colonists had their losses coming. They—and now we who inherited their sins—should have stayed in Europe.

The Numbers

“But to yield up the public domain out of historical guilt, when these lands will do little if anything to alleviate either [the Indian’s] situation or ours, is to misunderstand both our needs and to mistake a symbolic gesture for a genuine helping hand,” countered Watkins. As a culture, we may regret elements of the history that shaped the public lands, but as to who owns them today we must agree. We all own them; we all need them; to reemphasize, every acre was “forged in necessity.” This is it; there are no more such lands where those came from. And finally national population is against us, too.

From 327 million in 2019, the Census Bureau predicts the U.S. population will rise to 450 million by 2050—perhaps 600 million by 2100. So what if those numbers are off a bit? They are whoppers given our shining cultural preference—millions of acres of vacant land. Either we keep the public lands intact or lose what makes us unique, becoming, as Watkins feared, just another country without a landed ideal on which to renew the national experience.

And what would be wrong with that, revisionists refuse to cool their narrative? Perhaps the national experience should not be renewed and the public lands returned to their “rightful” owners. Better that the United States just fade away.

This is further to trace—among contemporary environmentalists—how ridiculous even the Sierra Club has come to sound. Let Utah (or Weyerhaeuser) call for privatizing the public lands and most let out a howl. However, let someone at Harvard Law School propose it and suddenly the idea is unassailable, again provided that the recipient is a “deserving” victim as made legitimate by a “proper” history.

As Watkins enumerated, the requested land transfers could be immense. Notable examples in 1974 included Havasupai claims to Grand Canyon National Park and National Monument. All told, the 1974 Indian Claims Commission was considering 250 cases, “bringing the total [native] claim to 200 million acres, all from the public domain.”

In hindsight, the largest of those transfers, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, has been deemed an unqualified success. Certainly, its beneficiaries have never disputed that—and why would they?

But should not the entire nation have benefited, Watkins asked? Fast forward again to the $12 billion backlog allegedly hamstringing our national parks. What if Alaska’s public lands, still generating revenue for every citizen, had instead helped pay for that?

Mud

"Because the natives were here first, Dr. Runte, and think of all the treaties we broke! Man, you just don’t get it!"

No, I get it. I am supposed to repent my Eurocentric sins by reading Karl Marx and banning Mark Twain. T. H. Watkins knew to uphold Twain. No one, least of all Watkins, wanted to push natives off the public lands. But own them? Control them? How would Huck Finn—or any one of us—then escape “sivilization” for “the Territory?”

As for past treaties, Watkins was the first to insist they be honored, but in money and not in land. In part, the United States has in fact already done that by allowing natives exclusive rights to tax-free casinos. Meanwhile, nothing is stopping us, here borrowing from Marx, from returning the land under the houses we own.

The inescapable history remains: With world population nearing 8 billion, every acre on this planet has at some point been wrested from someone else, and indeed—again borrowing from critical theory—who is to say Columbus “invaded” anything? Is a discovery an invasion? Only in your mind.

Old German for “mud,” my surname bespeaks what motivated Europe to perpetuate the discovery. Undoubtedly, during the middle ages, my ancestors inhabiting the Rhineland worked in marginal fields prone to flooding. Those living above us, probably in castles—and undoubtedly to whom we owed our entire crop as rent—called us serfs. Speaking of which, doesn’t Germany owe me something for their suffering? Are the middle ages out of bounds?

Actually, I had planned to make my claim much more immediate. My paternal grandparents, aunts, and uncles suffered the ravages of Nazi Germany. All of my father’s inheritance—and therefore mine—was wiped out in World War II. Again, who do I get to blame? Would Angela Merkel at least let me into the country to partake of its social benefits? I can’t show her a deed, but there must be a treaty somewhere she still needs to honor.

This is to reemphasize, getting back to Watkins, what distinguished the environmental movement he knew from today’s. Today’s no longer agrees, as did the “old” movement, that America’s effectiveness in conservation rests entirely on how we treat our public lands. In that case, no one gets to claim aggrieved status, for that only perpetuates a crippling mistrust. Oh, sure, we’re all in this together—until someone insists they’re special.

Watkins, certainly, remained blunt. All of us must renounce our “ancient history.” Whoever our ancestors were—and however they got here—none of us is immune to bad behavior. “Overgrazing, strip-mining, resort development, clearcutting on Northwest timber lands. . . . None of this is to suggest that the Indian is any more inclined to misuse the land than his counterparts in the white world, only that he has shown in more than one instance that he can.”

Climate change itself is but a radicalized substitute for the backbone environmentalists used to have. It was the public lands that made for their real authority. A secure land base can adjust to climate change, but absent the base nothing is secure.

No wonder, fleeing my bluntness, Watkins lost himself in the crowd. Why belabor the inevitable? He had lost the war—and he knew it.

Take the recent (January 2018) so-called DeFazio-Walden-Wyden-Merkley bill (as passed, the “Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act”). It was through Congress and onto President Trump’s desk with little discussion, let alone debate—finally to award, in trust for the tribes, 32,261 acres of BLM land in Oregon (50.4 square miles), worth an estimated $161 million.

Here especially, we are not supposed to ask what strange bedfellows brought forth this handsome giveaway. Normally, Oregon’s powerful Democratic senators (Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley) are vocal critics of President Trump. As is Congressman Peter DeFazio (D-4th District). But not here, and indeed, why not here? Dare we say it the way the Sierra Club used to say it? Because this raid on the public trust benefited them.

The disclaimer “in trust” aside, the land will never come back to the public—all Americans. The so-called fairness of the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act was to benefit a single group of claimants.

The point is: What if it had been Grand Canyon again? Or Yosemite, Yellowstone, or Glacier? Olympic National Park has 35 billion board feet of timber. Yes, billion. What if, now on the Olympic Peninsula, others demanding “fairness” come after that?

The Perfect Storm

Can’t happen, you say? But it can—and has (See Public Law 112-97, 112th Congress, February 27, 2012). The late Carsten Lien, author of Olympic Battleground, in fact considered the law but the opening wedge portending the loss of every rain forest in the park.

Bears Ears? Grand Staircase-Escalante? Utah still did not get the land, is the point. It remains with BLM. The state only succeeded in reducing the monuments. In Oregon, your public lands went on the auction block—and no one at CNN said a peep.

But the tribes will take care of their windfall, right, including trees estimated to be 400 years old? Hardly. Not only did they get to cherry-pick from the best BLM timberlands in western Oregon, selling the timber is exactly what they intend.

This, in 1974, remained the essence of Wakins’s fear. If unopposed, anyone was capable of cherry-picking from our public lands and resources. The assumption “by now has acquired the unquestioned validity of gospel,” he noted, “that by instinct, training, and tradition the American Indian is a superior steward of the land, and that by giving it over into his care we may actually be saving it from the depredations of white society.”

But again, white society was hardly the only culprit. “No one with eyes to see or ears to hear is going to argue that the impact of white society on the American environment has been anything less than a disaster,” Watkins acknowledged. That said, the Indian himself “was frequently willing, even eager, to alter the fragile balance on which his very survival depended.”

Were Watkins still with us, I doubt he would recant this much. Whenever poor history is combined with political ambition, it makes for a perfect storm. Worse, if the ambition happens to be economic (and most ambition is), those defending the public interest lose.

Under the Obama Administration, ambition masked as necessity targeted the public lands for renewable energy. Who would deny Google, General Electric, Vestas, et al., the land they required for saving the planet? Of course they could have purchased private lands (and ideally, lands already considered marginal), but that would have cost their stockholders money. Instead they demanded, in the words of the Los Angeles Times, that tens of thousands of acres of pristine desert “take one for the team.”

Yes, Team Perfect Storm, and again, did anyone really ask the Mojave Desert? No. Rather, with the election of Donald Trump, the press forgot all about Mr. Obama’s land grabs.

The point everyone forgets is how both political parties have perfected covering their tracks. When convenient, each party quietly lets the other take the lead, as necessary, shedding a few crocodile tears after the fact. The Democrats forced our hand. Had we protested the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act, they would have called us racists. The Republican Party is covered, Mr. President, and you’re covered. Go ahead and sign the bill.

Still when it comes to undermining our public lands the political parties are one and the same. They only differ about the most “deserving” recipients. The Democrats start the process with feel-good intermediaries, among them green corporations and Indian tribes. The Republicans would make the awards straight to the states—and let them reward the party faithful.

Yes, it’s that simple—and always has been. It only gets complicated when someone like T. H. Watkins dares to challenge everyone’s bedrock self-interest. Danger! Don’t touch this history! We will blow your reputation to smithereens if you do.

Watkins did touch it, for which I still admire him, for it was indeed the right thing—and the courageous thing—to do. The nothing history threatening our public lands is real—and the national parks still in its sights. We believe in the corruption of history at the peril of our parks—and our country. Next time, think about that when Congress awards any reparation or “gift” of your public lands. You lost—and posterity lost. What your government allegedly gave back to its rightful owners means your rights no longer count for a thing.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

What a clear, factual historical perspective Dr. Runte provides on baseline principles behind public land, air and scenic vistas preservation. Only vigilant public owners of our public lands can protect them from commercial exploitation by whomever is chasing a buck.

This is a must read for anyone interested in preserving public parks for generations to come. Debasing our natural heritage via public land grabs to exploit valuable natural resources is wrong no matter who authorizes it or who does it -- regardless of their official title or race.

Interesting essay. Thanks!

Painting the scary spectre of "yielding up the public domain" raises barriers to the opportunity to work in partnership with native communities that frequently share conservation, education, and even tourism goals with the NPS. While collaborative management has been promised (sound familar) in federal law and policy, with few exceptions NPS has been reluctant to embrace native partners, and not very good at it when they've tried. Moving forward as park managers - almost regardless of what you believe about reparations or reconciliation for ancient wrongs - our time would be better spent examining and emulating examples of constructive collaboration between protected areas and indigenous populations tin Canada and elsewhere than defending the ramparts against the native hordes and their lawyers.

A surperb essay by Dr.. Runte that should be required reading by everyone interested in our national parks. Dr. Runte reminds us of the importance of history in our great system of national parks.

I would like to troll many sides here.

First, Mr. Runte trots out a Holocaust line when the German government has indeed (sometimes and reluctantly) offered reparations for victims of the National Socialist era - beginning at a state-to-state level in 1953 and continuing to the contemporary EVZ! A historian could be bothered to do an internet search or phone his local library information desk (206-386-4636 is a good place to start).

Second, Parks Canada is notorious for excluding First Nations bands from joint management of its iconic parks. There was a huge expose in The Walrus of these issues in 2017, even! Giving Inuit communities in Nunavat some say over parks that no one goes to is one thing (and not that different from what happened in the US with the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act) but letting Stoney bands run Banff (or even hunt or gather there) has always been another. They are no model.

Third, this is such a historians' issue. The dispossession of indigeous people that created the public domain mostly happened prior to the establishment of national parks and national forests. Like cities and European-style agriculture, they are a consequence of a much, much bigger process. However, only a few histories deal with the continuance of indigenous people in urban and less scenic rural spaces. Because - unlike parks - they aren't as tied up in myths and counter-myths of the West that seem to fascinate historians.

I am in the process of readin "Black Hills, White Justice", and we being a Nation of laws and at times lording over other countries regarding human rights, have the Supreme Court saying that yes, the Sioux Nation, by treaty, has never relinquished the Black Hills, but we can't just give the Hills away, so we insult the Sioux and offer them money, which they do not want. Mount Rushmore, Wind Cave and Jewel Cave are all on Sioux lands by law that is pushed aside.

I want to thank Dr. Runte for his very clear, intelligent, and articulate reminder of our responsibilities to respect and protect our public lands. His thoughtful and thought provoking message is timely and clearly necessary. Not only does he address the issue of preserving invaluable resources for future Americans, he most importantly addresses the current mania for distorting historical facts. With adept humor, without rancor or mean spirit, the message he presents is remarkable. Please share these truths because our governmental bodies and our independent media watchdogs apparently will not attempt to inform or explore such subjects anymore.

I applaud Dr. Runte's courage, intestinal fortitude, insight, and mien.

I get it. Danke.

I'm replying to "Canada."

Runte just scratched the surface. What about the West Coast potlach culture, where slavery was hereditary and slaves, being prpperty, were killed at potlaches?

As for the Stoney? They would be among Plains Indians that, before the Columbian contact, used buffalo jumps to overhunt bison, if the population had been big enough to make that problematic enough to call it "overhunt."

It's not just "such a historians' issue." The belief that American Indians/First Nations were, or are, Rousselian "noble savages" has consequences today, and Runte just scratched the surface there, too. And, that's why the myths and counter-myths fascinate historians -- because the general public continues to grasp at them.

Take the "peaceful Hopi" nonsense. Anybody who knows Awatovi knows its nonsense. Anybody who knows that scalp clains at both Hopi and Zuni existed to at least the start of the 20th century knows it's nonsense.