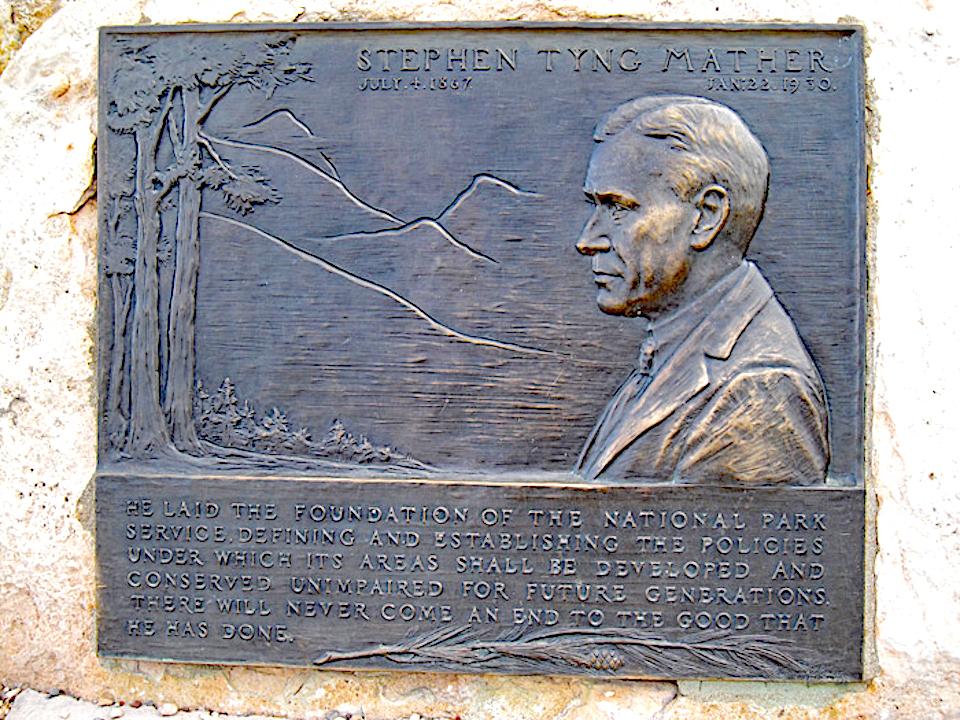

A Mather Plaque at Petrified Forest National Park/Kurt Repanshek

Editor's note: The following is an abridged version of G. Arthur Janssen's article on the Mather plaques that can found around the National Park System. You can find the full version at the National Park Service History eLibrary.

It had always seemed obvious to me that Grand Canyon’s Mather Point should have a sign explaining who it was named for. People who are camping in the Mather Campground and attending ranger programs in the Mather Amphitheater and enjoying the view from Mather Point would begin to wonder who this Mather person was. To make it clear that Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, was appreciated at Grand Canyon, the NPS had installed not just a normal wayside sign, but a large, artistic, bronze plaque paying tribute to him.

Since I had always associated the Mather plaque with Mather Point, I was puzzled when I first noticed the exact same plaque in another national park. It seemed incongruous, almost as if another park bore a sign explaining the view from Hopi Point. Had this other park made a copy of Grand Canyon’s sign? I asked a ranger about their plaque, but he didn’t know anything about it. Over the years I noticed the Mather plaque in other parks, but no one seemed to know how it had gotten there. The rock strata beneath Mather Point remember 1.7 billon years of events, but park rangers come and go more quickly, and even the National Park Service, which is officially dedicated to remembering history, holds many memories only on papers buried in archives, if at all.

Eventually I contacted the national headquarters of the National Park Service and asked about the history of the Mather plaques. In response to my inquiry, NPS historians queried one another, but no one knew much about it. Fortunately the folks at the NPS Mather Training Center in Harpers Ferry had remained more curious about their namesake, and they supplied me with a 1997 research paper by David Nathanson that provided a good start.

The last line on the Mather plaque, “There will never come an end to the good that he has done,” was spoken by Michigan Congressman Louis Cramton on the floor of the U.S.House of Representatives in January, 1929. Cramton served on the House Public Lands Committee, and was one of Congress’s strongest supporters of Stephen Mather and the National Park Service. Cramton spoke on the occasion of Mather’s resignation as director of the NPS, but since Mather had suffered a stroke and the prognosis was poor, Cramton’s remarks had the ring of a eulogy.

A year later, on January 22, 1930, Mather suffered another stroke and died. Soon after Mather’s first stroke and resignation, his friends and supporters started a private organization, the Stephen T. Mather Appreciation, to plan some sort of memorial to him. The executive committee was full of prominent names, including Gilbert Grosvenor of the National Geographic Society, General John J. Pershing, and Congressman Cramton. They came up with forty-two ideas for memorials,and had a lively debate about them. There was strong opposition to the idea of a plaque, including opposition from Mather’s friends inside the National Park Service, including Horace Albright, who had succeeded Mather as director.

Mather had always disliked the idea of plaques, statues, and other human monuments inside the national parks. National parks were supposed to be about the grandeur of nature, not about the transient heroism of politicians, generals, or explorers. When admirers of John Muir had come to Mather and proposed that a small plaque honoring Muir be placed in Yosemite, Mather had refused, even though John Muir was Mather’s hero.

Stephen Mather shared John Muir’s vision of nature as not just beautiful and ancient, but sacred, a refuge for the human spirit. A California native, Mather made trips to the Sierras, climbed mountains, and joined the Sierra Club when it was only a dozen years old. Mather met and had a long talk with John Muir, who filled Mather with indignation at the despoiling of the Sierras. Yet the national parks and America’s conservation movement now required something more than just vision and indignation. They required someone with the political and managerial skills to build an agency, inside the U. S. government, that could defend and expand the national parks against powerful economic and political forces. It required someone with the rare combination of Stephen Mather’s personality and experience.

In 1893 the young Mather, working as a newspaper writer, was hired by the Pacific Coast Borax Company to come up with an advertising slogan for its borax soap and detergent. Mather came up with the slogan and image of the “20-Mule Team” brand. The president of the borax company disliked Mather’s idea, but Mather prevailed, and the borax company made a fortune. The 20-Mule Team, invoking the romance of the Wild West, became one of the enduring advertising symbols of the 20th century. Later Mather started his own borax mining company and made his own fortune, but Mather also observed the greed and machinations of mining companies and other private interests.

In 1914 Mather wrote a long letter to the Secretary of the Interior complaining about how private companies were threatening the national parks, and about how poorly the national parks were being managed.The Secretary of the Interior replied that if Mather didn’t like the way the parks were being run, he could come to Washington and run them himself, as director of a new National Park Service.

Mather put his skills as a salesman and manager to work building a loyal constituency for the national parks, building the National Park Service, and expanding and improving the park system. Mather built a coalition that spanned bird watchers, artists, politicians, and railroad corporations. He set high standards for the national parks, enduring standards that have made America’s national parks the model for the world.

Even when railroad corporations had become crucial allies for bringing the public to the national parks and for fighting off powerful mining corporations, Mather ordered the Union Pacific Railroad to decentralize its plans for its lodges at Zion, Bryce, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon so that human architecture wouldn’t compete too much against the scenery. And yes, even when lovers of John Muir wanted to place a tribute to Muir in Yosemite, Mather disliked the idea of national parks looking like every courthouse square in America.

In the end, Mather was persuaded to allow John Muir into Yosemite. In the end, the Stephen T. Mather Appreciation decided on a bronze plaque. Horace Albright reluctantly went along: “I did not want to stand in the way of the activity of the Mather Appreciation group.”

Hoping for something special, the Mather Appreciation selected sculptor Bryant Baker to create the plaque. On April 22, 1930, three months after Mather’s death, Baker had received enormous national publicity with the dedication of his Pioneer Woman statue in Ponca City, Oklahoma. Forty-thousand people attended the Pioneer Woman statue dedication ceremony and heard Will Rogers praise the statue and the American pioneer spirit it represented. Baker’s design for the Pioneer Woman statue was selected in a national contest in which 750,000 people had voted among twelve contending models for the statue. Over six months the models had toured from museum to museum, from coast to coast, and stirred up great public interest and newspaper publicity.

The statue and the contest were the idea of E. W. Marland, an Oklahoma oil tycoon who would also serve as Oklahoma’s governor and congressman. Marland was a great admirer of the American pioneers and felt that pioneer women hadn’t been sufficiently honored for their role in building America. In 1926 Marland invited twelve prominent sculptors to a dinner party, promised them $10,000 just for creating a model for a Pioneer Woman statue, and $100,000 if they won the public contest. Many of the sculptors were more famous than Baker, such as Alexander Stirling Calder, who had done the statue of George Washington.

The Mather Appreciation was hoping to place plaques in all 56 of the national parks and monuments of the time, but at first they cast only 25 plaques for the National Park Service,and three more for state parks. For unknown reasons, Mount Rainier National Park received two copies of the plaque. Two later generations of plaques would be cast in the 1950s and 1980s, adding about 30 more plaques, though this wasn’t enough to keep up with the proliferation of new parks and monuments.

HE LAID THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE. DEFINING AND ESTABLISHING THE POLICIES UNDER WHICH ITS AREAS SHALL BE DEVELOPED AND CONSERVED UNIMPAIRED FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS. THERE WILL NEVER COME AN END TO THE GOOD THAT HE HAS DONE. -- Inscription on the Mather plaques.

Today 59 sites are known to have Mather plaques, but this count may not be complete. Stephen Mather’s 65th birthday would have been July 4, 1932, so on and around that date a dozen national parks and monuments held dedication ceremonies for their plaque. The continuing respect for Stephen Mather within the NPS, and the continuing creation of new national parks and monuments, led to a continuing demand for new Mather plaques.

In 1958 a second generation of plaques was created, though this was initiated from outside the National Park Service. Chicago was planning to dedicate a Stephen Mather High School in 1959 and wanted a Mather plaque for the school. A relative of Stephen Mather contacted NPS Director Conrad Wirth about obtaining a plaque. Wirth contacted Bryant Baker, who contacted the Gorham Company, but it turned out that they no longer possessed the model of the original Mather plaque, which had probably been destroyed during World War Two when Gorham cleaned out much old material to clear space for war-related work.

Baker told Wirth they could use one of the original 1932 plaques as a model, and Wirth volunteered the one in the hallway outside his office. As Wirth thought about the opportunity and queried his NPS colleagues, he decided that the NPS should cast fourteen new plaques for newer parks. Baker contacted two other foundries to obtain estimates for making new plaques, and Wirth agreed to pay Baker to supervise the process.

A third generation of plaques was cast between 1986 and 1991. This casting was initiated by Colorado National Monument, which wanted a Mather plaque to celebrate its 75th birthday in 1986. They obtained the 1932-edition Mather plaque from Wind Cave National Park and made a mold from it. In anticipation of the 75th anniversary of the National Park Service in 1991, other parks and monuments were given the chance to obtain a plaque, and many responded. This new edition is aluminum but colored to look like bronze, and on the backside it says “Colorado National Monument Edition.”

Stephen Mather owed his entire career to his conceiving the “20-Mule Team” brand for borax soap and detergents. In the 1920s the borax company campaigned for the creation of Death Valley National Monument, with the help of Horace Albright, who’d grown up near Death Valley, and later on the borax company donated land for the creation of a Mission 66 visitor center.

In its courtyard the visitor center holds a Mather plaque, dedicated in 1991. I once attended a history talk in that courtyard, given by a history-minded ranger. Afterward I asked him about their Mather plaque, and he went over and looked at the plaque as if he had never noticed it before. He didn’t have a clue about what the plaque was doing there.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Thank you for doing the research on this!

As I'm a proud National Park junkie, I am a fan of Stephen Mather. I find it hard to believe that an NPS ranger wouldn't know about Stephen Mather and the reason for the plaques and places named for him. There's a 1951 biography Steve Mather of the National Parks by Robert Shankland. I did read somewhere that a new biography/history of Stephen Mather and national parks is in the works, probably from a university press. The Shankland book is not scholarly, but definitely aimed for the general reader. That's not necessarily a bad thing, but there are interested people who think the time is ripe for a new study and biography of a man who did a lot to change America's landscape.

Ken Burns "National Park Series" has excellent commentary and biography of Stephen Mather. A great man who has inspired many. God bless you my friend, you came before your time and are truly missed.

Albright was more than just a local guy who grew up around Death Valley, his father and Christian Zabriskie were partners. Zabriskie became F.M. "Borax" Smith's raight-hand man and most trusted VP & GM of Pacific Coast Borax. When Horace Albright departed the NPS, he went onto work for the Borax Co at their Potash operations in New Mexico, so in mnay ways Death Valley and Borax gave birth to NPS... (The daughter of another main Borax player, Harry Gower, married an Albright son... so even more connections.)

Amazing how the right person comes along at the right time.....

A great article about a great man who should never be forgotten by the National Park Service.

I happened to see one of these plaques in Sequoia, maybe somewhere near Giant Forest, on the west side of General's Highway. At what might have been a pullout at one time but was unmaintained.

I always wondered about the origin of the plaques at Mount Rainier and others I've spotted elsewhere. Now I know more about them. Thanks for the article!