Tent cabins in Yosemite's Half Dome Village experienced the largest percentage price increase in the study's sample/David and Kay Scott

If you enjoy vacationing in America’s national parks, it’s likely you’ve noticed park lodging has become more expensive – in many cases, considerably more expensive. The days of finding national park lodging, even rooms without a private bathroom, for under $125 are mostly in the rearview mirror. A few remain, but they are increasingly rare, even during the offseason. Today it’s not unusual to pay from $200 to $300 per night for a guest room or cabin in a national park.

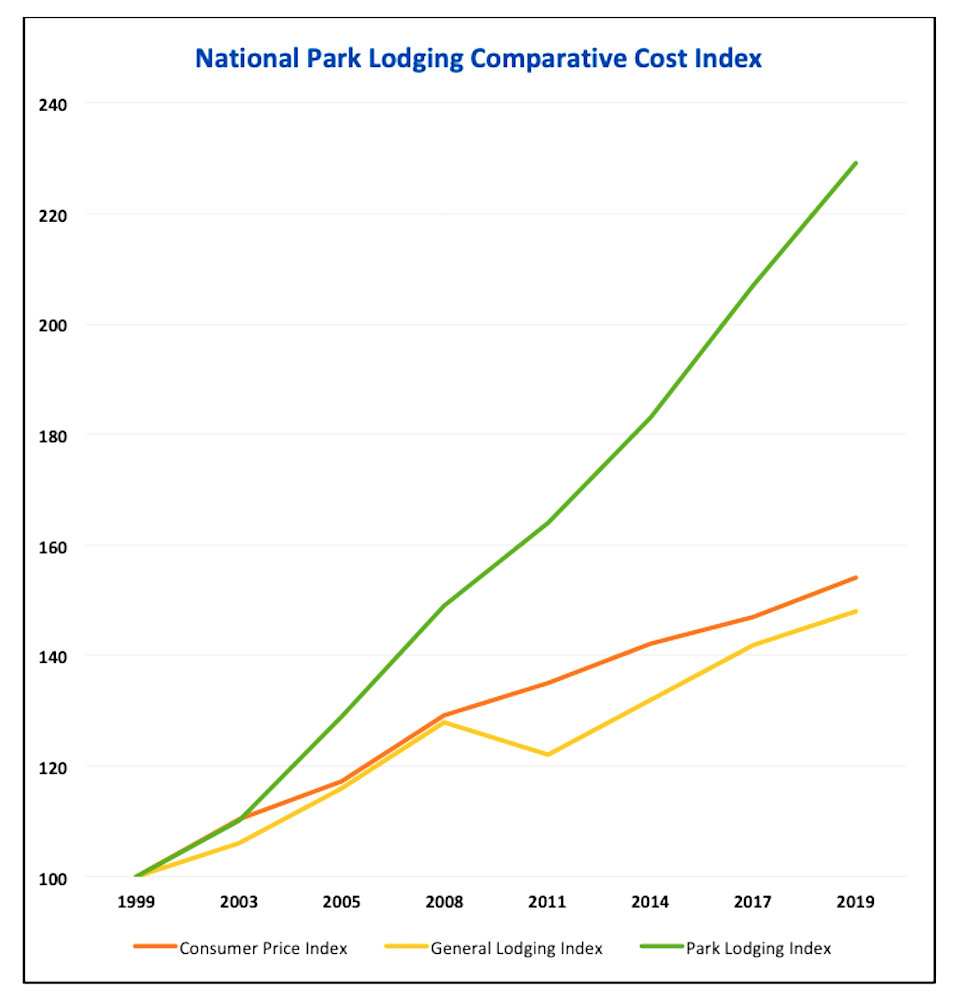

Two decades of touring the parks while gathering information for revisions of our book on the national park lodges included compiling years of lodge room pricing. The accumulated data offer an opportunity to construct a cost index for lodging in America’s national parks and determine the degree to which prices have actually increased. We compared our price index for national park lodging with the Consumer Price Index and the cost of lodging away from home calculated by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Our national park lodging cost index is calculated over the two-decade period (1999 – 2019) during which we gathered price data. The index represents guest room prices at 34 different lodges spread among 19 national parks. For some of the more popular parks, several lodging facilities are included in the index.

In calculating the overall cost index, we first computed an index for one particular type of room or cabin at each of the selected lodging facilities. In Virginia for Shenandoah National Park’s Big Meadow Lodge we chose to track the price of a cabin. In Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky we utilized prices for Historic Cottages (formerly classified as “Hotel Cottages”). For Paradise Inn in Mount Rainier National Park in Washington state we used a room with a private bath. In some instances we had to use our best estimate because the concessionaire changed room designations during the 20-year period. For example, Headwaters Lodge & Cabins at Flagg Ranch (formerly Flagg Ranch) in John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway in Wyoming increased room categories from two to three after a new concessionaire took charge.

For 2019, the final year of the index, we checked guest room prices for the coming summer at each of the lodging units included in the sample. This wasn’t always easy, because some facilities, such as Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim and cabins at Roosevelt Lodge and Cabins in Yellowstone National Park, tend to be full from the opening date to the closing date, which means room prices aren’t available online. We had to keep trying until a reservation was cancelled and a room came open.

A price index is calculated off a base year set equal to 100. For our index we established the base year as 1999, the initial year for our record of national park lodging prices. The index value of a particular lodge for each subsequent year indicates the degree to which prices changed. An index value above a 100 means prices have increased while an index reading below 100 indicates prices declined subsequent to the base year. A 2006 Consumer Price Index of 121 indicates consumer prices increased 21 percent since 1999.

Since our calculations occurred in March, the Consumer Price Index and the index for lodging away from home weren’t finalized for 2019. So for the current year we used the consensus assumption of a 2 percent inflation rate for consumer prices and a slightly higher 3 percent rate of inflation for lodging away from home. These may turn out to be off by a little, but not enough to taint the results of the study.

Our index for national park lodging pricing is unit weighted. In other words, each lodging facility is equally weighted in calculating the overall index. Thus, changes in the price of a tent cabin in Sequoia National Park's Grant Grove has the same importance as changes in guest room prices at Yosemite National Park’s Majestic Yosemite Hotel. A price-weighted index, had we used one, would have biased the results such that expensive lodges would overwhelm price changes for the less expensive lodge rooms.

The graph above illustrates national park lodging price increases significantly outpaced changes in both the Consumer Price Index and the index for general lodging. The final 2019 national park lodging price index of 229 indicates our sample set experienced an overall 129 percent increase during the last two decades. In other words, a room that cost $100 per night in 1999 would be expected to cost $229 in 2019. This equates to an annual compounded increase of 4.23 percent compared with an annual increase of 2.17 percent in the Consumer Price Index and an annual increase of 1.98 percent in general lodging. Based on our sample of 34 lodges, national park lodging room rates have been increasing at approximately twice as much as the Consumer Price Index.

National Park Service staff in Washington, D.C., pointed out that the National Park SErvice Concession Management Improvement Act of 1999 governs concessionaire rates. That act states that, "concessioners must set reasonable rates subject to NPS approval. The law indicates the approval process must be based upon market forces and the reasonableness of rates must be determined primarily upon comparison with those rates and charges for facilities, goods and services of comparable character under similar conditions, with due consideration to factors such as length of season, location, cost of labor and materials and others."

NPS spokeswoman Kathy Kupper added that,"(C)oncessioner rates are subject to annual review and approval by park managers. In some instances, approved rates increases may track closely to a consumer price index). In other cases, the changes in prices for comparable hospitality and recreation services may be higher than a particular CPI and this may be reflected in the concessioner rate changes."

"For example, in 2014 and 2015, the all urban consumer CPI annual change was 0.8 and 0.7 while the average daily rate increases for hotels was reported at 4.7 percent and 4.5 percent respectively," she noted. "Rates may also increase if there is a change in amenities or facility improvements that result in a better visitor experience, consistent with prices one would see comparable properties that had such changes."

The largest percentage price increase in our sample -- more than 250 percent -- was a tent cabin in Yosemite’s Half Dome Village that rose from $40 in 1999 to $141 in 2019. This represents an annual compound growth rate of 6.5 percent, or three times the annual increase in consumer prices. The smallest price increase was at Kettle Falls Hotel in Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota, where over two decades room prices increased only 3.8 percent, from $65 in 1999 to $90 in 2019. This represents an annual compound price increase of 1.64 percent. Rooms at the hotel do not have a private bath.

At Yosemite National Park, spokesman Scott Gediman said rates for the tent cabins were established through a comparison process in which similar lodging facilities outside the park were located and their rates examined. Comparables looked at included Yosemite Bug Rustic Mountain Resort, in Midpines, California; El Capitan Canyon Campground, in Santa Barbara, California; Costanoa, in Pescadero, California, and; Fernwood, in Big Sur, California. Some of the rates at those destinations ranged above and below the Half Dome Village rates.

The most expensive lodging in our sample is in Wyoming at Grand Teton National Park’s Jenny Lake Lodge, where a cabin for two adults in summer 2019 goes for $799 per night. The price includes breakfast and dinner, but no lunch. These cabins rented in 1999 for $380 and have more than doubled in price. Cottages at Jackson Lake Lodge in the same park increased in price by 162 percent over the two-decade period during which consumer prices increased 54 percent.

David and Kay Scott are authors of “Complete Guide to the National Park Lodges” (Globe Pequot). Visit them at mypages.valdosta.edu/dlscott/Scott.html. Listen to their Traveler podcast about national park lodging at https://nationalparkstraveler.libsyn.com/national-parks-traveler-episode-2-lodging-in-the-parks.

Other articles in this series include:

New Lodging In America’s National Parks

National Park Lodges That Vanished

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

The NPS and the Concessioners should limit lodging to US citizens only. The high demand for Park housing by rich foreigners has priced out the American woorking people form their own Parks, The Parks are for the enjoyment of the American People not hordes of foreigners. At least give US citizens a big discount as compared to foreigners for lodging. Jeeny Lake Lodge charges $799 per night. Who can afford that? The 1% club of the world, not the American working person.

The reason for the increase... The outsourced booking agency the national park system uses.

Sounds like a case of capitalism! Hurray for the Country! Supply and demand has rased the prices. Occupancy rate is up, jobs are being created and the Natl Parks are thriving!

Well, the xenophobe contingent has been heard from. As usual, their opinions are outside the norms of conduct.

How about a no on that? Recreation.gov is only used for reservations where the federal governemnt directly operates or doesn't specifically use a concessioner, such as camping. However, camping could be contracted out to an operator who isn't necessarily a concessionaire (like California Land Management). I've stayed in a campground operated by a concessionaire, and I had to book directly through that concessionaire's website.

Each concessionaire uses its own booking system. A large one like Xanterra has one that's more or less unified though. One can look up a reservation at any of their locations across their system.

My big issue is that inevitably when it comes time to renovate they've taken out the economy units and replaced them with more expensive ones. Even in a vacuum, this tends to bring overall prices up. For example, when Giant Forest Village was removed from Yosemite National Park, it was replaced with Wuksachi Lodge which cost more than twice as much. In my grand 2006 trip, two of my budget in-park lodging locations are now gone and the replacements are considerably more expensive.

For those promoting the virtues of the free market and capitalism, $799/night represents the law of supply and demand. Apparently there are "hordes" of people willing to pay that much.

I agree. At Grand Teon's Signal Mountain campground (operated by a concessionaire) most of the campsites were recently "upgraded" with electrical hookups. Campers who don't want or need electrical hookups end up paying extra for it regardless. With no reservation system you have to take what's available and the cheaper sites go first.

Yes, capitalism is thriving in the National Parks but capitalism is not the mission of the Parks, The Parks aren't thriving, concessioners are. The Parks are over-crowded and often in poor repair. Ban foreigners from Park lodging and there will be an increased supply of ldoging and more affordable prices of lodging for the Amercian People. It's simply suppy and demand.