On a partly cloudy August morning, my two children and I were launching our kayaks into the Blackwater River in Maryland, a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay, when we spotted a blue crab just beneath the water at the river’s edge. Sitting comfortably in some mud, and almost hidden by a marshy sedge called Olney’s three square, the crab smoothly sidled away from our kayaks as we paddled by. I wondered how many more of these “beautiful swimmers”—as author William Warner famously called them—were there beneath the water, out of sight.

It turns out that there are about 405 million of them in the Chesapeake Bay, according to the July 2020 findings of the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee, which performs an annual survey of crab populations. In an August blog post, Chris Moore, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s senior regional ecosystem scientist, noted that while current numbers represent a drop from the estimated overall crab population in 2019, which was 594 million, and the number of adult females, an important indicator of overall population health, dropped from an estimated 191 million to 140 million in the same time frame, crab populations are fairly consistent with previous recent years, particularly 2013 and 2018.

“In general, the population has been more robust since a new bay-wide management plan was agreed to in 2008,” Moore stated in the blog post. “One of the best indicators of this increased abundance has been the fact that we have been above the target abundance for adult female blue crabs twice since 2008, after exceeding it just once between 1990 and 2008.”

Blue crab populations are an indicator of the Chesapeake Bay's health/Jarek Tuszyński

The largest estuary in North America, the Chesapeake Bay is a nationally significant, biologically rich, and economically productive waterway--and the heart of a 64,000-square-mile watershed. In his journeys through the bay between 1607 and 1609, Captain John Smith wrote that the bay interior “may have the prerogative over the most pleasant places known, for large and pleasant navigable rivers, heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man's habitation.”

But the bay has also, at times, been one of the most polluted watersheds in America, with ecological “dead zones” that were first discovered in the 1970s. Since then, however, the bay has rebounded into a mostly healthy and productive ecosystem, the result of federal, state, local, and nonprofit partnerships, including significant National Park Service involvement, that have worked towards the watershed’s protection.

Most lovers of the Chesapeake know that, as the watershed goes, so goes the crabs. Blue crabs have long been the centerpiece of a historic and valuable commercial and recreational fishery. In 2019, commercial crabbers hauled in about 61 million pounds of blue crabs from the bay and its tributaries--up slightly from roughly 55 million pounds in 2018, according to the July 2020 report, and recreational crabbers reaped about 3.8 million pounds of crabs in 2019, similar to the previous year.

Ecologically, the crab is a vital part of the ecosystem, serving as forage for many species of fish and birds. Although current population numbers mean the crab population is holding steady, CBF’s Moore says more still needs to be done to ensure the long-term health of the bay and the plant and animal species that rely on it. Reducing the level of nutrients and polluted runoff from farms and lawns before it reached the bay’s tributaries, mitigating climate change and the weather changes it engenders, and improved water quality all would continue to boost the bay’s health.

Kayaking and canoeing are among the most popular activities on the bay's waters/Kim O'Connell

Although there is not, as yet, a comprehensive national park unit devoted to the Chesapeake Bay, the National Park Service maintains a strong presence in the region, maintaining a Chesapeake Bay office that works closely with state agencies as part of the Chesapeake Bay Program, formed in 1983 to coordinate ecological restoration efforts, as well as the Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network, a public-private partnership of parks, refuges, museums, water routes, and more.

As part of this work, NPS also oversees the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, established in 2006 as a series of water routes that trace the explorer’s navigations. Operated as part of Colonial National Historical Park, trail staff have placed particular emphasis on telling the stories of indigenous people that interacted with the bay historically and who still do today, through several ongoing tribal connections and partnerships. “We also do a ton of paddling programs that get kids on the water and connect them with that historical water-based experience,” says Kym Hall, Colonial superintendent. “We ask them, ‘What does the health of these waterways have to do with the history? What does the health of these waterways have to do with what’s happening here today?’ There’s a strong nexus.”

NPS also works closely with the Chesapeake Conservancy, which advocated for the establishment of the water trail along with other sites and park expansions along the bay (such as the Mallows Bay National Marine Sanctuary). The Conservancy is now working to promote the creation of the Chesapeake National Recreation Area.

“Most of the great landscapes in the nation have some representative national park unit,” says Conservancy President Joel Dunn, “but the Chesapeake Bay—one of the largest environmental restorations in the world, the largest estuary in North America—does not. We believe that a national park unit will create more public access, which is absolutely a driver for creating conservationists, while celebrating Native American history, Black history, our watermen, and more. We hope it will be an international and national spotlight on the Chesapeake Bay.”

Water-level view of some of the bay's landscapes/Kim O'Connell

This month, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan sent a letter to Maryland Senators Ben Cardin and Chris Van Hollen advocating for legislation to create a Chesapeake Bay National Recreation Area, and Van Hollen is reportedly interested in taking the lead on crafting the bill. “Maryland is fortunate to have several exceptional [national park] units located here, but there is no one unit devoted solely to the Bay,” Hogan wrote. “I believe the Chesapeake is as grand as the Grand Canyon and as great as the Great Smokies and should be included in a new federal-state partnership.”

In a similar letter sent in August to Virginia Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam wrote that “Established as an official unit of the National Park System, a Chesapeake Bay National Recreation Area would elevate the Chesapeake Bay and bring additional national and international recognition. More importantly, it would bring greater National Park Service expertise and resources to the Chesapeake Bay area and restoration efforts, and establish more public access points to the bay itself.”

Kym Hall remembers that, years ago, the stories about the Chesapeake were always about how to bring the bay back to health. “To think about shifting that narrative to ‘It’s so awesome here that you want to come play and recreate,’ that feels symbolic of recovery,” she says.

“The NPS logo holds a lot of weight,” Dunn says. “My dream and vision is to generate significant private philanthropic funding to support the national park. I think it would bring together our community in a positive way, and it would be a great response to the Covid crisis. It would be a great response for the call for equity in our community. There’s a legacy element to this that’s really important to me. I want future generations to appreciate and enjoy the Chesapeake like we have.”

Traveler footnote: Beginning on National Public Lands Day (Sept. 26) and continuing through November 14, the Chesapeake Conservancy is sponsoring its first-ever virtual footrace called “Champions for the Chesapeake.” Funds from the race will support efforts to establish the Chesapeake National Recreation Area. You can register at this page.

Paddling Through History On The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail

By Kurt Repanshek

Editor's note: The Chesapeake Conservancy is advocating for creation of a Chesapeake Bay National Recreation Area as part of the National Park System. It's a rich cultural, historic, and recreational setting, as the following story from 2015 illustrates.

We knew we were being watched. We skimmed across the water, with our paddle blades rising and falling in a quick cadence. From its tall perch atop a pine, a bald eagle slowly rotated its white-feathered head and kept its eyes on us as we paddled further across Menokin Bay towards Cat Point Creek.

Though this bay is said to be the Rappahannock River's largest tributary, with several holes plunging more than 30 feet deep, our five kayaks were alone on the water. Only the birds watched us, though there could have been an otter or beaver looking on from the understory along the shores. Moments earlier we had slipped into the bay's tea-colored water and now, having crossed the Menokin with its numerous duck blinds and rimming marshes, our small flotilla of red, blue, yellow, and cedar-strip kayaks threaded the creek's narrow channel that cuts across Virginia's Northern Neck and ties back into the Rappahannock.

The banks were overgrown. There were Loblolly pines, Sweet gums, oaks, cedars, and sycamores. Nodding waves of wild rice, cattails, Marshmallow, Switch grass, Great bulrush, wild iris, grew along the shore. This marshy tangle forms a thick veil along the two shores, and hemmed us in as the channel thinned. It was home to great blue herons, belted kingfishers, osprey, tiger swallowtails, and marsh crabs.

Captain John Smith presumably encountered a similar scene sometime between 1607 and 1609 (one historian puts it at July 1608) during his explorations of the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries. The Englishman was searching for the mythical Northwest Passage that would provide a quick route to the Orient, but three years of exploration failed to find it, because it didn't exist. But the captain did discover a place where, as he wrote in his Description of Virginia in 1612, "the mildnesse of the aire, the fertilitie of the soil and the situation of the rivers are so propitious to the nature and use of man as no place is more convenient for pleasure, profif and man's sustanence."

The Chesapeake Bay is the nation's largest estuary. It, or its tributaries, borders parts of Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, reaches into New York and Pennsylvania, and even to West Virginia. Many rivers drain into the Chesapeake, and America's earliest colonial-era cities were situated at or above the fall line of these rivers, including Richmond, Virginia, on the James River, Fredericksburg, Virginia, on the Rappahannock, Washington, D.C., on the Potomac, and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on the Susquehanna. Other streams and rivers'the York, Patuxent, Nanticoke, Choptank, and Elk, to name a few, drain more than 64,000 square miles of land.

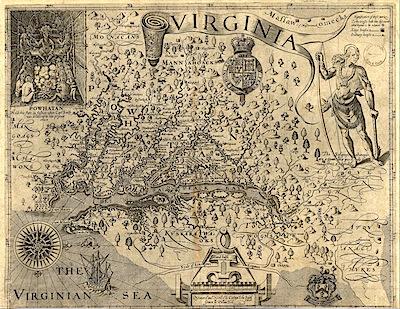

Captain John Smith's map of the Chesapeake region was published in England in 1612. It locates more than 200 Indian towns, and carries an illustration of Chief Powhatan.

The Chesapeake, with its waterscape and surrounding countryside, offers one of the most enticing trail networks in the entire National Park System. Along the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, more than 2,000 miles of shoreline, counting all of the backwaters, coves, bays, rivers, and streams, await paddlers. It was here that the National Park Service launched the nation's first national water trail in 2006. It's perfect for a canoe, kayak, and even a Stand Up Paddleboard in places. Occasionally visitors will even watch a 60-foot trawler pass by.

The trail blends our country's foundational history with current events. Charming towns are home to the working watermen who harvest blue crab, oysters, and shad (which author John McPhee called the 'founding fish'). And there are seemingly endless miles of water-supported recreation. You can boat, fish, or simply cool off in a river or bay.

What's the best way to approach this watery treasure? That's almost beside the point. There are well-known areas, and not-so-well-known areas. There are places where you must count your strokes. There are places of solitude, where the heavily vegetated shorelines close in on you, and practically embrace you. There are places where you can close your eyes, and feel the rise and fall of your boat with the currents. You'll wish the day was longer.

I found myself on Cat Point Creek on a drizzly, late-May day when the air temperature was struggling to reach 65 degrees Fahrenheit and the sun wasn't going to shine. The creek ties Menokin Bay, on the north side of the neck, with the Rappahannock River on the south. Four centuries ago, Smith and his crew took their 28-foot 'shallop' up the Rappahannock. They made it as far as present-day Fredericksburg, where the Great Falls on the river forced them to turn back.

When Smith explored these waters, he counted more than 200 Indian villages, and mapped the coastal areas that supported agriculture. At one point the captain feared for his life after being stung in the arm by a stingray. Another time, he was reportedly held captive by Indians.

There's a possibility that Smith even followed this route up Cat Point Creek across the Neck, though on this day I wasn't searching for evidence of that. Rather, with Suzanne Copping of the National Park Service and Richard Moncure of Friends of the Rappahannock, I simply wanted to gain a sense of the vast possibilities of paddling the Captain John Smith Trail.

My normal paddling waters are the big lakes of Yellowstone National Park and the fast, rapid-filled rivers that roar through Dinosaur National Monument. While there would be no rapids this day, only a subtle tidal shift and a living landscape, the history held in this countryside is rich and deep. It reaches back to the country's birth, and before. To reach our put-in on Menokin Bay, we traversed the plantation once owned by Francis Lightfoot Lee, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Long before Lee there were at least two Indian settlements here along the 19 miles of Cat Point Creek.

The Menokin Foundation is Restoring the Past

You don't need to paddle to enjoy this trail, as history and beauty runs right down to the waterline. Our group headed to the Cat Point Creek put-in, but before dipping a blade we briefly explored the remains of Francis Lightfoot Lee's 18th century mansion. Lee was one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, and had a particularly generous father-in-law. Upon his marriage in 1769 to Rebecca Tayloe, John Tayloe II gave the couple not only the property along Menokin Bay, but also paid for construction of their Neo-Palladian home. Click here to read the rest of the story.

Heading out across the bay, Moncure pointed out that we were seemingly passing through time, from the 1700s of the Menokin settlement to farther back to the days of Pocahontas. We inched up the creek, and were soon ducking beneath snarls of branches and dodging tree trunks that time, and strong winds, had toppled into the water. The current was sluggish and not a challenge, though the creek banks closed in, and made it tricky to maneuver. While it's possible to slowly navigate across the Neck into the Rappahannock, that was not in our plan this day. We were just out to enjoy one small stretch of the water trail.

The creek might seem inconsequential when you consider the more than 2,000 miles to be explored, but its waters are considered to be some of the cleanest in the watershed. Its setting reminded us of what once was found across the Chesapeake landscape. The connection to Menokin, where the Menokin Foundation is working today to preserve the skeletal remains of Lee's home, is just one spot where partners such as the National Park Service, state agencies that operate parks, and nonprofit groups such as the Friends of the Rappahannock', meld their skills and talents to bring significant depth and breadth to the trail, both on the water and on the surrounding lands.

After the morning paddle on Cat Point Creek, Ranger Copping and I headed out with our kayaks for a launch site on the Rappahannock River below Fones Cliffs. This sheer, four-mile-long, 100-foot-tall cliff is studded with fossilized shark teeth and scallop shells. Thanks to the river's fish, as well as the healthy geese and duck populations, the cliffs are also home to one of the highest concentrations of bald eagles on the Eastern Seaboard. We spotted a few as we paddled the river's warm waters, as well as a few herons. We wished we could linger.

Captain Smith's journals describe three American Indian settlements above the cliffs and a skirmish with a few dozen Rappahannock warriors. But today the main threat here is development, which could lead to homes atop the cliffs, though there is an ongoing attempt to purchase the land to add to the adjacent Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge.

Below the cliffs, the current is slow, and the rain continues. But we're not about to let these showers drive us to shelter. Captain Smith surely wouldn't have, so we paddled on.

Resources

A Boater's Guide to the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail

This softcover guide, produced by the National Park Service in partnership with the Chesapeake Conservancy and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, is a good resource. It provides a deep overview of the water trail, and offers trip itineraries with notations for the optimal watercraft. Maps pinpoint trailheads, and there is some historical perspective on Capt. Smith. You can download the entire guide, or just portions you are interested in.

Yes, There's An App for The Water Trail

Download the free Chesapeake Explorer App for your smartphone; it can help you identify more than 50 units of the National Park System in the region, locate other national trails, find places to hike, bike, fish and paddle, craft cycling or driving tours, or get directions to lighthouses, museums.

Comments

The Chesapeake Bay is NOT as grand as the Grand Canyon Governor. This is called Pork Barrel. The people of the Chesapeake Bay region don't need more federal regulations.

Let's not make an NPS unit out of everything.

One of the most historically signficant places in the country and continues to be a lifeblood of many. Certainly deserves consideration.

Gosh, Loui, I think I might have a solution. If you and your friends can get together and negotiate the restoration of all the lands ripped away from Bears Ears and Grand Staircase Escalante National Monuments, we might get so preoccupied with repairong all of the damage done to those lands since their protections were removed that we just might be too busy to worry about the Chesapeake Bay. Why don't you get busy on that idea?

It is great to hear about this initiative. Chesapeake Bay is not only nationally, but also globally significant. It would be a park with unique and outstanding natural, historic, and recreational values.

This was made clear in the National Park Service Special Resource Study, which was done in the early 2000s https://web.archive.org/web/20050205211934/http://chesapeakestudy.org/st...

Unfortunately, the study was completed during the George W. Bush administration, so the preferred alternative was a watered down approach that did not involve an actual Park System Unit.

But the NPS clearly concluded that Chesapeake Bay was qualified for designation as new national park unit. The study report stated that:

https://web.archive.org/web/20050205210349/http://chesapeakestudy.org/np...

A National Recreation Area would be a step in the right direction. But NRAs are focused primarily on recreation, while Chesapeake Bay has a far broader set of values. Based on the research by RESTORE: The North Woods of hundreds of potential parks, Cheasapeake Bay should be a full National Park, alongside Everglades, Acadia, and Yellowstone. The park could include not only key lands along the Bay, but also important Bay waters.

There is a growing scientific consensus that to mitigate climate change, we not only need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, but also to maximize the removal and storage of carbon from the atmosphere. Forests, wetlands, and the ocean (along with grasslands) are the world's most important carbon sinks. A Chesapeake Bay National Park would preserve and restore these critical ecosystems.

Biologists agree that we need to save from 30% to 50% of the Earth for nature if we are to avoid massive extinctions of plants and animals in the coming decades. Less than 7% of the lower 48 United States meet this standard. A Chesapeake Bay National Park would encompass some of the most biodiverse lands and waters in America.

Emerging research shows that direct contact with the natural world is not only enjoyable, but it measurably benefits our health and well-being. A Chesapeake Bay National Park would be within ready access of tens of millions of people, many of whom have inadequate access to nature.