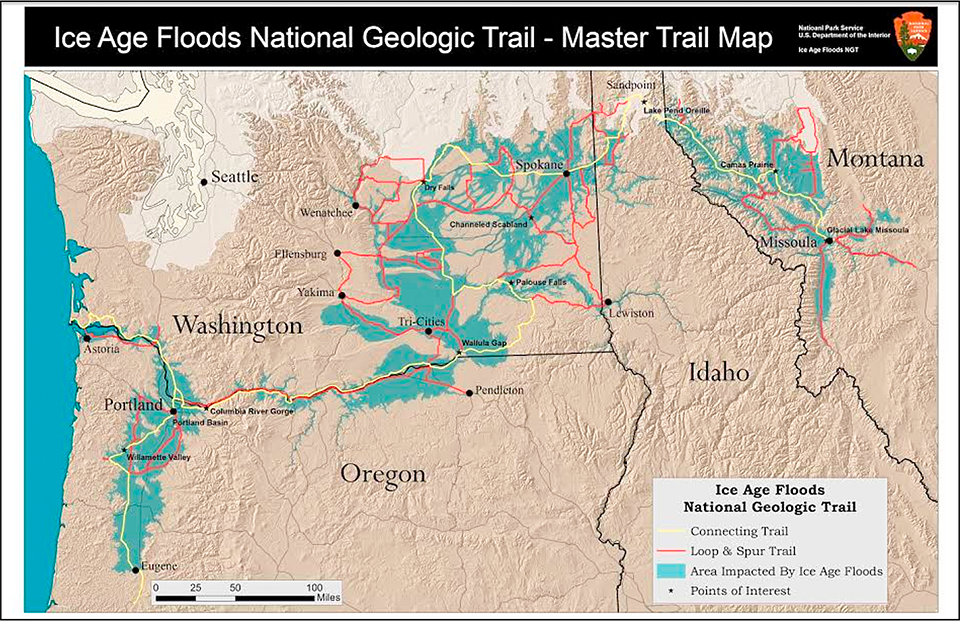

Map of the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Ice Age Floods Institute

I have a feeling the National Park System will see heavy visitation this summer – at least, the top 25 most visited parks are probably going to see their fair share of people. Of the National Park System’s 423 units, however, there really are all sorts of places to visit at which you can take in the fantastic landscapes, watch the wildlife, learn new things, and not be jostled by huge crowds. Not too long ago, the Traveler even hosted a webinar discussing some of those “overlooked gems.” But there are more wonders to see than were even reviewed in that one-hour webinar.

This year, instead of a 10- or 15-hour drive to a national park unit, I plan to stick a little closer to home, taking day or weekend trips. Most recently, I packed my cameras and myself into my vehicle and began driving to sights along the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail. Like the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, the Ice Age Floods NGT is not a hiking trail but rather a route over which the colossal floodwaters of Glacial Lake Missoula flowed some 18,000 – 13,000 years ago at speeds of about 65 mph (approx. 105 kph) from Montana through swaths of Idaho, Washington state, and Oregon, ultimately emptying into the Pacific Ocean.

Much like a glacier, these floodwaters plucked and carried rich, fertile soils and truck-sized boulders great distances beyond their points of origin, eroded the landscape, and gouged deeply into the fractured rock, leaving behind great, deep, wide ravines known as coulees in Eastern Washington. These miles-wide coulees with columnar basalt cliffs reaching hundreds of feet high are known as the Channeled Scablands.

The path of the Glacial Lake Missoula floodwaters through the Pacific Northwest / U.S. Geological Survey

It’s difficult to really fathom the immensity of it all unless you see it in person. Hopefully, these images and how I got them will fire up your own photographic creativity and tempt you on road trips tracing the path of this national geologic trail.

West Bar Ripples

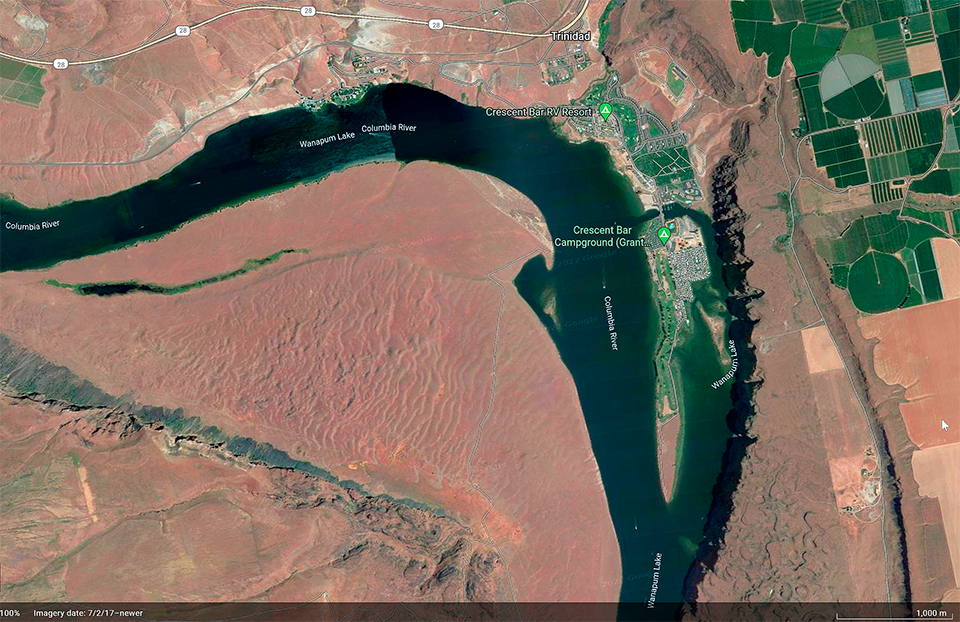

I began my morning driving northeast from my home in Yakima, Washington, to the small community of Trinidad, and from there, to a spot Google Maps calls the “Columbia River vantage point”. There’s even a little camera icon there, indicating it’s a nice spot for taking pictures: a gravel area just off of Crescent Bar Road NW providing an expansive view of the Columbia River and West Bar ripples.

Satellite image of the West Bar ripples in eastern Washington, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Google Earth

As author John Soennichsen writes in his book Washington’s Channeled Scablands Guide, “Many scabland features are hard to measure with the naked eye when viewed from a distance.” If you decide to drive to this spot yourself, remember to bring along your telephoto lens in addition to your wide-angle lens, because from the Columbia River vantage point (and at any wide shoulder or pullover within the area, for that matter), the undulating landscape far below looks like ski slope moguls, when in reality, those hills are giant current ripples, just like ones you might see along a riverbank or beneath the clear water of a lake. According to Bruce Bjornstad’s On The Trail Of The Ice Age Floods, “West Bar is one of the best and most classic examples of giant current ripples anywhere along the paths of the Ice Age floods.” Those ripple marks measure between 24 - 40 feet (7 – 12 meters) tall, are 360 feet (110 meters) apart, and are “composed of boulders up to 4.5 feet (1.4 meters) in diameter.”

West Bar giant current ripples from the Columbia River vantage point near Trinidad, Washington, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Geologists believe the size of the ripples are indicators of water depth: the deeper and faster the water, the larger and more well-defined the ripples. In this one area, the depth of the floodwater is estimated to have been 650 feet (198 meters) deep – deeper than where I stood photographing the landscape. That means thousands of years ago, the floodwaters flowed way above my head! Note: it’s believed the Ice Age floodwaters creating the West Bar ripples came from Glacial Lake Columbia several centuries later after Glacial Lake Missoula’s flooding trickled to a halt. So, although created by a different set of Ice Age floodwaters, these mega ripples are still part of the scabland landscape.

Looking south to the West Bar giant current ripples, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

If you ever want to see and photograph these giant current ripples for yourself, I recommend a morning or late afternoon visit when the sun’s angle will be most conducive to shadows defining the ripples’ shapes.

A telephoto view of giant current ripples, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

A telephoto close-up of the West Bar ripples, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

To add a little comparable scale to your images, make sure to include those buildings in the distance or the trees along the riverbank.

Moses Coulee

To really get a feel for the immensity of these scabland coulees, you should drive or hike through one. After photographing the West Bar ripples. I spent a good part of my morning driving through Moses Coulee via Palisades and B-SE Roads, alternating between pavement and gravel. Quail darted across the roads and green ribbons of groundwater-irrigated farmland spread all the way to the base of the coulee walls.

The roads through Moses Coulee, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Google Earth

Moses Coulee landscape, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

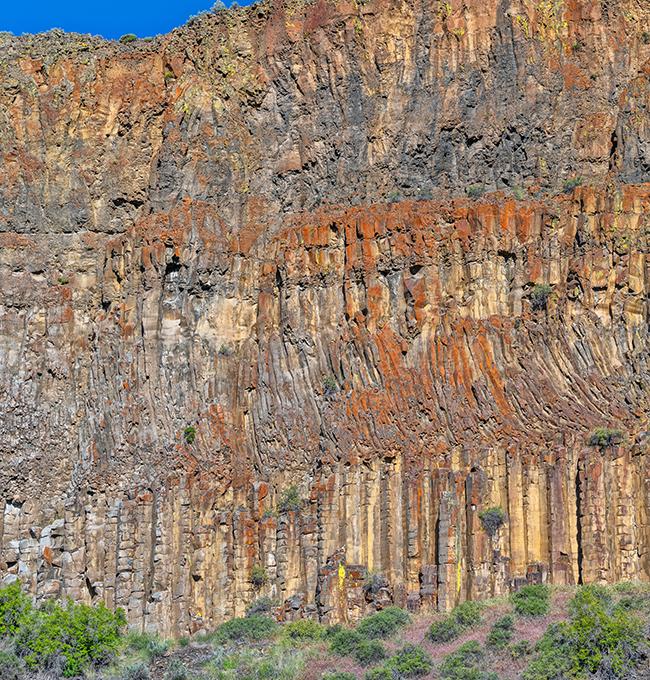

S-shaped Moses Coulee is the second-largest and westernmost of the scablands in Eastern Washington. Towering cliffs hundreds of feet tall created from layers of basalt lava flows that cooled into hexagonal columns, border the broad coulee floor dotted with farms, ranches, rock formations, and a few lakes.

Moses Coulee columnar basalts, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Moses Coulee columnar basalts close-up (how many layers do you count?), Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

If you follow this same route, then do stop at a wide shoulder or pullover along B-SE Road to capture a shots of the columnar basalts comprising the coulee walls paralleling the road. Look closely to see the boundaries separating different basalt layers, each representing a separate eruption and lava flow. In the image above, I count four, maybe five separate layers. Get a wide-angle shot to show your audience the overall cliff view, then a telephoto close-up of the columnar basalts.

The road down Moses Coulee, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Heading up and out of Moses Coulee, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Photograph a leading line image or two using the road within the coulee. I captured a photo looking back from whence I came, and another looking toward the road leading up, out, and onto scenery once covered by a glacier.

Regarding those road images above, you might take note of the amount of “negative space” I left in the shots. Think of negative space as empty or blank space such as water, sky, or grass above, below, or around the subject. In these photos, the negative space is the sky. I could have cropped out some of the sky to focus more on the vista below the horizon, but I left each shot as-is because I feel all that sky/negative space emphasizes the width and breadth of Moses Coulee.

Dry Falls

A satellite image of the Dry Falls area, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Google Earth

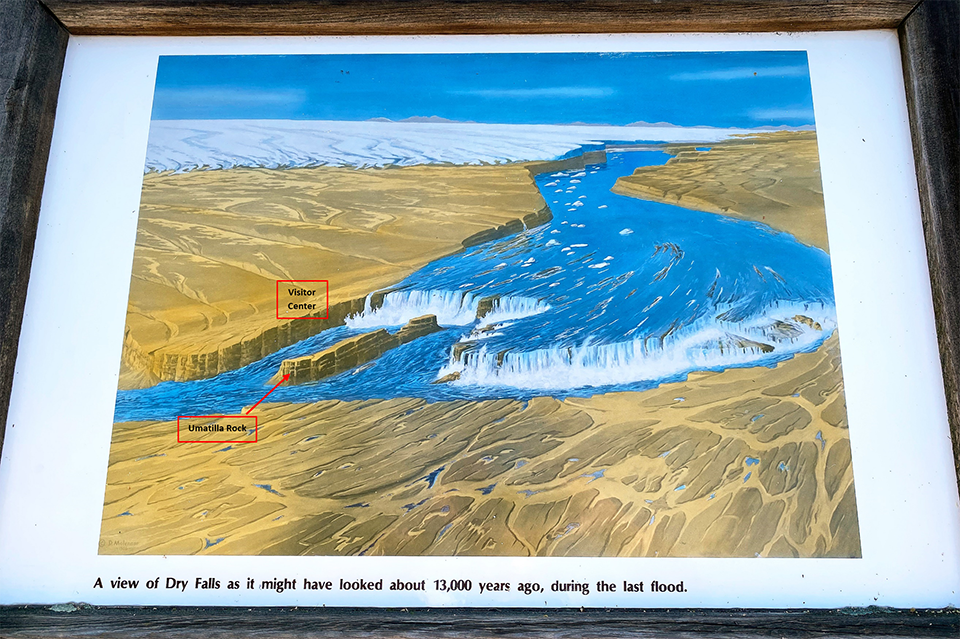

Niagara Falls is considered the most powerful waterfalls in North America, but thousands of years ago, there was a waterfall that overshadowed Niagara in size and sheer power. According to an informational brochure I picked up at the Dry Falls Visitor Center, Dry Falls is “the skeleton of one of the greatest waterfalls in geologic history. It is 3.5 miles (5.6 km) wide with a drop of more than 400 feet. By comparison, Niagara, 1 mile wide with a drop of only 165 feet, would be dwarfed by Dry Falls.”

A view of Dry Falls as it might have looked 13,000 years ago, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Washington State Parks

The visitor center and Dry Falls landscape, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

The Lower Grand Coulee, part of the Grand Coulee proper and location of Dry Falls, is designated by the National Park Service as a National Natural Landmark. Stop at the Dry Falls Visitor Center for awesome shots looking over and beyond the basalt precipice of a vast, once-flooded scenery with turbulent waters that eroded away fractured basalt rock and created the plunge pools you see below, now “a series of tranquil groundwater-fed lakes and an oasis for wildlife.”

Dry Falls vista, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Pull out your SLR camera’s wide-angle lens (wider than 24mm, if you have it) or use your wide-angle setting on your point-and-shoot or smartphone as you walk along the edge of the coulee wall, past the visitor center, for all-encompassing compositions of the entire panorama from different perspectives.

Looking southwest toward Sun Lakes-Dry Falls State Park, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Don’t forget to capture photos looking southwest toward Sun Lakes-Dry Falls State Park, too. This park lies on the scoured-out path created by these massive Ice Age floodwaters.

A closer look at Dry Falls landscape, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Use your telephoto lens or telephoto setting for a closer look at those basalt cliffs and coulee landscape.

Arrive too early (or too late) in the day, and most, if not all, of the Dry Falls area will be in deep, dark shadow. Believe it or not, the best views are closest to noon, when the sun shines directly down to fully illuminate the coulee topography. Of course, that means a little atmospheric haze over the landscape’s upper regions. A circular polarizing filter helps, but there may still be some residual haze in your image. If you use Adobe Lightroom, there’s a dehaze slider that’s useful in removing much of the haze, and of course, there are photo editing plug-ins with dehaze options as well.

Once you arrive at the bottom of the coulee, the atmosphere clears up for little-to-no-haze in your photos. And you do want to drive down into the coulee to Dry Falls Lake for eye-level images as well as views looking up to where you earlier stood.

Dry Falls and Dry Falls Lake, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Drive into Sun Lakes-Dry Falls State Park and follow the signs toward the gravel road that takes you all the way back northeast to Dry Falls Lake. Warning: drive very carefully along that gravel and dirt road. It’s not well-maintained (for all I know, it’s not maintained at all), narrow, uneven, rocky and scattered with potholes. A 4-wheel drive vehicle, or one with good tires should help with maneuverability.

Perch Lake, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

A serene spring day at Perch Lake, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

While navigating the rocky road to or from Dry Falls Lake, stop at Perch Lake for a bit of photography in that spot. it’s a serene little water body in a beautiful setting with “surround-sound” birdsong.

A red-winged blackbird in the cattails at Dry Falls Lake, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Speaking of birdsong, while admiring the Dry Falls Lake landscape, remember to just stop and listen. No talking, no singing, no music from your EarPods. Just listen. You’ll hear insects buzzing, wind in the tall grasses, and a plethora of birdsong, even if you can’t see which birds are singing because the cattails hide them.

The rocky road to Dry Falls Lake, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail / Rebecca Latson

Don’t forget to get another leading line shot of the gravel road to or from Dry Falls Lake. The image here makes the road look relatively well-maintained. Don’t be fooled. This just happened to be a level portion and made a decent stopping spot to get the shot.

One more thing to remember: whatever you photograph, be it landscape or a specific feature like mega ripples or columnar basalts, remember to take a time framing your image. You might be photographing for specific documentation, or for a fine art image but either way, your viewing audience will appreciate a nicely-composed shot.

It was a fine spring day for a short road trip and I’m not finished by a longshot with my travels along the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail. Stay tuned as I continue my explorations.

Note: Rangers are out and about at Washington state parks, so rather than risk a fine, you’ll need to purchase a $10 day pass or $30 annual Discover Pass. You can purchase your passes ahead of time online at https://www.discoverpass.wa.gov/ or you can use the payment kiosk at Sun Lakes-Dry Falls State Park prior to the turnoff onto the road toward Deep Lake and Dry Falls Lake. You can pay $10 cash or use a credit card with their automated system (which unfortunately did not work during my visit – so bring cash just in case).

References

Ellensburg Chapter, Moses Coulee Ice Age Floods Institute Field Trip 2018

John Soennichsen, Washington’s Channeled Scablands Guide, 2012,The Mountaineers Books

Bruce Bjornstad & Eugene Kiver, On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods, The Northern Reaches, 2012, Keokee Books

Bruce Bjornstad, On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods, 2006, Keokee Books

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

WOW. Great grouping of photos and explanations. Thanks for sharing.

Great start. Hopefully there's more to share.