Books are damn hard to write.

And let me be clear. I don't rank guidebooks, such as the ones I've written, with novels, be they fiction or non-fiction. Guidebooks are little more than encyclopedic accounts of a place. I would venture that most anyone, paired with a good editor, could get the job done.

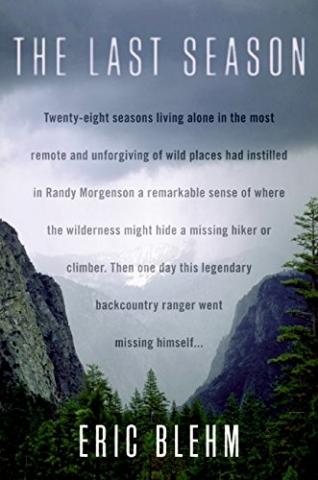

At the same time, there's just so much sweat and imagination and painstaking work and reflection that goes into a novel, fiction or non-fiction. That's why I'm so impressed with Eric Blehm's The Last Season, an account of the disappearance of Randy Morgenson, a backcountry ranger who spent 28 seasons in Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks before vanishing into a void.

It's a mystery that perhaps will appeal largely only to parkies, but it's one masterfully told.

Regardless of your opinion of Ranger Morgenson by the time you finish cruising through Mr. Blehm's 327 pages, you have to be impressed with the task the author shouldered. What's amazing, at least to another writer, is that Mr. Blehm spent eight years researching this book. Eight years!

Ranger Morgenson obviously got under his skin, so much so that he couldn't shake the trials the ranger encountered both in the backcountry, with the National Park Service, and in his personal life. I would hazard a guess that writing the book became a cathartic experience for Mr. Blehm, one he no doubt was happy to see come to fruition when it was published earlier this year.

In piecing together Ranger Morgenson's life, Mr. Blehm takes us back to the ranger's boyhood in Yosemite National Park, where his father became something of a celebrity as a self-taught naturalist. And then he takes us forward, through the young man's infatuation with the backcountry, his scholastic endeavors that he eventually tossed aside to spend as much time as possible in the backcountry of Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks, and his love of a woman.

In taking us on this journey, Mr. Blehm relies on numerous interviews with Ranger Morgenson's fellow rangers and becomes almost an intruder as he peruses the ranger's backcountry journals. Through it all he creates an image of a man who seemingly seeks to channel both Ansel Adams and Wallace Stegner, two environmental giants of the 20th century that Ranger Morgenson knew on a personal level.

It's both an intriguing and mystifying image, one that led me near the book's end to wonder whether the ranger wasn't a misplaced 19th-century romantic who no longer could bear the 20th century's company. Mr. Blehm helps create that impression by salting Randy Morgenson's writing throughout the text, such as the following that opens Chapter 3: "Only this simple everyday living and wilderness wandering seems natural and real, the other world, more like something read, not at all related to reality as I know it," the ranger wrote in his journal at his backcountry station at Charlotte Lake, Kings Canyon National Park, in 1966.

Prefacing the first chapter, Mr. Blehm drops this bombshell from Ranger Morgenson: "The least I owe these mountains is a body."

In telling this story, Mr. Blehm at times pulls back the drapes of a window, at least partially, into the culture of the National Park Service when he describes the birth and evolution of backcountry rangers.

"The administrators in the Park Service often refer to them as 'the backbone of the NPS.' Still, they were hired and fired every season with zero job security. Their families had no medical benefits. No pension plans, And there was no room to complain because each one of them knew what they got into when they took the job. They paid for their own law enforcement training and emergency medical technician schooling. They were seasonal help. Temporary. In the 1930s, they were called 'ninety-day wonders' who worked the crowded summer seasons."

Too, the author sheds ample light on how Ranger Morgenson viewed humankind's intrusion upon the earth.

"We are the greatest bulldozers to walk erect," the ranger wrote into the summit journal on Sept. 8, 1971, when he reached the top of Mount Solomon, a 13,034-foot-high peak. "Will we ever permit, in a small place as here, Mother Nature -- truly our Mother -- to do her thing, undisturbed and unmarred. Will we ever be content to play a passively observant role in the universe, and leave off this unceasing activity? I don't wish man in control of the universe. I wish nature in control, and man playing only his just role as one of its inhabitants.

"I want every blade of grass standing naturally, as it was when pushed through the soil with spring vigor. I want the stones and gravel left in the autumn as spring meltwater left them. Only these natural places, apart from my tracks, give me joy, exhilaration, understanding. What humanity I have has come from my relations with these mountains."

The Last Season takes us into the mountains, both through one man's eyes and our's as interlopers curious as to what happened on July 21, 1996, when Ranger Morgenson headed out on what was to be a patrol of three or four days and failed to return.

But if we listen carefully as Mr. Blehm unfolds this story, we can learn much not only about Ranger Morgenson, but also about how much we care, or should care, for the marvelous landscape of not just Kings Canyon National park, but all national parks, and for the rangers who patrol them.

Comments