Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Mike Stickney, Director of the Earthquake Studies Office at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology.

Mitigating the effects of the 1959 Madison Slide required a complex response of federal, local, and private organizations. The joint efforts stabilized what could have been a secondary disaster of a flood following the Hebgen Lake earthquake.

The August 17, 1959, M7.3 Hebgen Lake earthquake caused incredible devastation throughout the greater Yellowstone region, and one of the most consequential impacts was the Madison Slide, which blocked the Madison River just west of Yellowstone National Park in Madison Canyon. Immediately after the slide occurred, the river began backing up behind the debris dam, flooding the canyon and forming what today is known as Earthquake Lake. Without intervention, this lake would have eventually overtopped the debris dam, potentially unleashing a flood that could have destroyed the town of Ennis, Montana, and other downstream communities along the river. The new lake might also flood and destabilize the Hebgen Lake Dam, upstream of the slide, adding to the potential consequences of inaction.

Because of these concerns, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) was called into action. On Thursday, August 20, ACE Major General Keith R. Barney, Missouri River Division Engineer, and members of his staff flew to the disaster area. They met with Hugh Potter, Montana Civil Defense director, and others on August 21. Later that day, General Barney engaged the consulting engineering firm Woodward, Clyde, Sherard and Associates to appraise the situation and advise on the stability of Hebgen Dam and the Madison Slide dam. On Saturday, August 22, Montana Governor Hugh Aronson requested the U.S. Secretary of Defense to direct the ACE to investigate and remove the serious threat to life and property, as this effort exceeded the technical and financial capabilities of the state and local governments. Later that day, General Barney directed Lt. Col. Walter Hogrefe, Garrison District Engineer, to proceed with the investigation and necessary emergency measures.

Also on Saturday August 22, a Congressional delegation arrived from Washington D.C. to survey the damage at the request of Montana Senator James E. Murray. They were met in Bozeman by Governor Aronson and a delegation of State officials, U.S. Forest Service personnel, and Yellowstone Park Superintendent Lon Garrison. The bipartisan, 21-member group and their escorts flew from Bozeman over the town of Ennis and the Madison Slide en route to West Yellowstone. In the afternoon, they toured the disaster area in helicopters and then were briefed on search and rescue efforts and the damage survey.

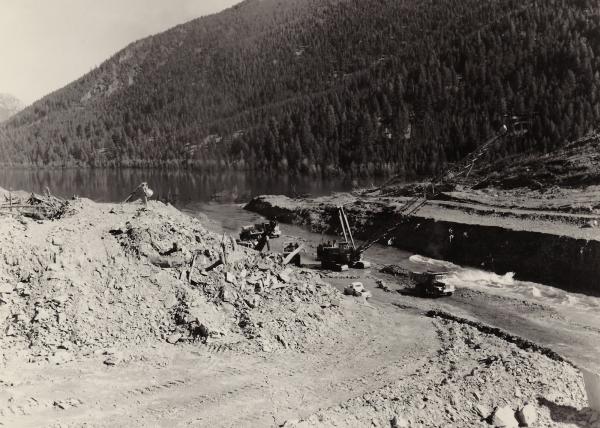

Dragline work to lower the outlet channel of Earthquake Lake on October 18, 1959. The tripod on the hill at center left is one of five lighting plants that allowed nighttime work. Note the “bathtub ring” of killed trees along the shoreline marking the high stand of Earthquake Lake before lowering of the outlet channel/Photo by Mrs. Steven W. Nile (Dr. Steven Nile was a physics professor at the Montana School of Mines [now Montana Tech

After preliminary investigations, the engineering firm recommended lowering the Hebgen Lake level, which would have the undesired effect of filling Earthquake Lake more rapidly. A project office (which included 54 ACE career employees and 18 temporary employees at the peak of activity) was set up in West Yellowstone on Saturday, August 22, and the following day a survey team began preliminary surveys for an access road on the downstream side of the Madison Slide and also an emergency spillway channel that would allow the river to pass over the slide without a catastrophic release of water. The U.S. Forest Service acquired 1:8,000-scale aerial photos of the slide and, using a Kelsh plotter (which allowed for detailed analysis of aerial photographs), generated a detailed topographic map of the slide with 5-foot (1.5-meter) contours (10-foot [3-meter] contours on the steeper south canyon wall). A similar map constructed from 1957 air photos allowed accurate determination of slide volume and other data for engineering uses.

On August 24, two dozers began work developing an access road to the top of the slide; work was completed by the following day. By August 27, 23 dozers were working on a 250-foot (76-meter)-wide spillway that would lower the eventual level of Earthquake Lake by 14 feet (4 meters). The open-pit copper mine in Butte was on strike, so an unusually large number of operators and equipment were available. By September, 62 pieces of heavy equipment and 190 operators and mechanics were working around the clock, with five lighting plants illuminating the night hours. During this period, Earthquake Lake continued to fill, flooding a number of cabins that were along the Madison River and floating them off their foundations.

The waters of Earthquake Lake began to flow over the new spillway on September 10 (accompanied by a ceremony attended by Governor Aronson and other state officials)—23 days after the earthquake and landslide. It rapidly became apparent, however, that the steep (14% grade) lower portion of the spillway was subject to deep gullying by uncontrolled erosion. Attempts were made to armor the lower spillway with large boulders (up to 100 tons) to control erosion, but this effort was unsuccessful. Because of the unique character of this project and associated problems, a Board of Consultants, all top experts in their fields, was empaneled. The board recommended lowering the outlet channel by 50 feet (15 meters). Three draglines were brought in and used to excavate a deeper spillway even as water continued to flow. Water flowing through the spillway was strategically used to remove slide material and help lower the spillway elevation, and a stable spillway configuration was achieved by October 29.

Earthquake Lake’s level dropped and then stabilized as water flowed over the spillway, and a “bathtub ring” along the lake shore indicates the highest level that water reached on September 10. Cabins that had floated off their foundations were unceremoniously deposited in a meadow as the waters receded and can still be seen today, informally known as the “ghost village.” Numerous standing dead trees that were once on the riverside now project from Earthquake Lake. Interestingly, those trees create a new habitat for fish that hide amongst the submerged trunks and branches.

Amazingly, with so much manpower and heavy equipment operating around the clock in a confined area, no lost-time accidents occurred. ACE estimated the cost of spillway construction and related activities at $1.715 million ($18.2 million in 2024 dollars).

Earthquake Lake, which formed when the Madison River was blocked by a landslide that occurred as a consequence of the Hebgen Lake earthquake in 1959. The lake inundated existing forest, now marked by standing dead trees in the lake water. The landslide scar is visible on the side of the mountain at the far end of the lake/USGS, Mike Poland, June 27, 2023.

The 1959 Madison Slide changed the landscape of the upper Madison River in the blink of an eye and profoundly affected the lives of all visitors in the area. This disaster brought federal, state, and local agencies together to solve unprecedented problems and mitigate future disasters. And both the impacts of the earthquake and slide and the subsequent remediation efforts can still be viewed today by anyone travelling along US Highway 287 along the north side of Hebgen and Earthquake Lakes.

For more information on landslide hazards in the United States, check out the U.S. Geological Survey Landslide Hazards Program.

Further reading

Madison River, Montana Report on Flood Emergency, Madison River Slide, U.S. Army Engineer District Omaha, Corps of Engineers, Omaha, Nebraska, September 1960; https://damfailures.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Army-Corps_Madison-River-Slide.pdf

J. B. Hadley, 1964, Landslides and Related Phenomena Accompanying the Hebgen Lake Earthquake of August 17, 1959; Chapter K, USGS Professional Paper 435, p. 107–138.

The Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology commemorated the 65th anniversary of 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake and the Madison Slide on their 2024 calendar. https://mbmg.mtech.edu/mbmgcat/public/ListCitation.asp?pub_id=32608&#gsc.tab=0

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Thanks, Mike! Very interesting bit of geologic history.